Academy Award-winning sound designer Johnnie Burn sits down with Michael Blyth to discuss how he created the haunting soundscapes of Jonathan Glazer’s harrowing Holocaust drama.

One could argue that the more skilled the sound designer, the more chance their work will go unnoticed. In a medium where visuals reign supreme, sound can struggle for attention, leaving the work of its practitioners sorely undervalued. ‘Even my mother once said to me, “What do you mean you do the sound on film?”’ recalls Johnnie Burn, a British sound designer, supervising sound editor and re-recording mixer, playfully acknowledging how his specialist area is often taken for granted. ‘Normally it’s just a magic ingredient,’ he suggests, before optimistically adding, ‘that sometimes has a bit more prominence.’

While such prominence is typically reserved for films with plots involving audio perception (Blow Out [1981] or Berberian Sound Studio [2012] spring to mind), Jonathan Glazer’s latest marvel, The Zone of Interest, dramatically foregrounds sound while thematically exploring silent complicity and a refusal to listen. Inspired by Martin Amis’ 2014 book, Glazer’s film – like his abstract reimagining of Michel Faber’s 2000 novel Under the Skin – is more evocation than adaptation. Straying significantly from Amis’ plot, this formalist (yet emotionally devastating) study of complacency and indifference in the face of Nazism, is rooted in the quotidian, where Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), house-proud wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) and their young children all enjoy their domestic idyll, seemingly unbothered by the disturbing noises that spill into their dream home from the concentration camp next door.

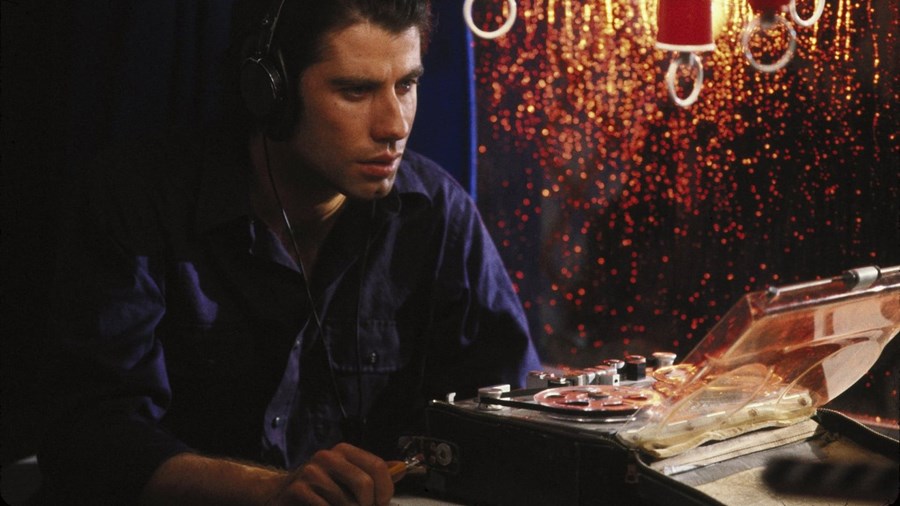

Blow Out (1981)

‘It’s a film with a huge contrast between visuals and sound, so much that when we were making it, Jonathan and I described it as two different films; one you see and one you hear,’ says Burn, whose work with Glazer dates back to the director’s iconic Guinness ‘surfer’ commercial from 1999. ‘I can’t think of a recent film that relies so heavily on a juxtaposed soundscape to create such a huge narrative impact. I’ve worked on films where occasional shots will use sound prominently, but The Zone of Interest is completely transformed by it. It’s great collaborating with a director who comprehensively understands that sound can be the narrative, and it can completely manipulate the way you understand an image.’

Given how pivotal sound would prove in shaping the film’s fundamental meaning, Burn knew this project would demand a particular level of commitment. ‘More than any other film, this required an enormous amount of research, which led to the creation of a vast library. Initially, I made a 600-page document. From that, we sourced and recorded vintage vehicles and guns from World War I, which were used in Auschwitz rather than on the front line. Jonathan and I were adamant that every detail had to be historically correct.’

In addition, there was an emotional truth that demanded equal care and precision. ‘Finding the cars or guns was just one aspect,’ explains Burn. ‘Understanding the interactions between the guards and the prisoners, being truthful to that, felt even more important. It was a year of research. We read all the witness testimony and felt an enormous responsibility to be respectful.’

Although crucial in offering a counter-narrative to offset the deceptively palatable images unfolding on screen, the film you hear did not begin taking shape until quite late into post-production. ‘Jonathan had to reassure people during filming that there would be bad stuff in this film,’ Burn recalls, ‘because the crew were like, “When are you going to film the horror?”’ The horror might be kept off-screen, but Glazer’s indirect approach is not to shy away, nor shield us. The evil at the heart of the film cannot be contained by concrete walls and barbed wire. Seen or not, it infiltrates its surroundings with the stain of complicity, just like the incessant drone of machinery, screams and gunfire that underscore almost every scene, polluting the otherwise pristine interiors of the Höss residence.

The Zone of Interest (2023)

Burn describes the film’s nauseating hum as ‘a kind of soup made up of many different noises – various machinery, the crematoria, the inner workings of the camp, etc – all of which came from the enormous library of content that we ended up with’. He also acknowledges the influence of composer Mica Levi in the creation of the signature sound. ‘Mica had written considerable amounts of music to underscore the film, but going through the process of understanding what worked and what didn’t, we realised a score made it feel like what we are seeing didn’t really happen. And that is what led us to put in the drone. So while some of Mica’s score didn’t end up in the film, it was instrumental in shaping the end result.’

The Zone of Interest (2023)

Premiering at Cannes, the film received the Grand Prix, while Burn took home the Prix CST for technical achievement. Not bad for ‘a self-taught sound designer who didn’t go to film school and learnt on the job’. While his on-set teachers include Yorgos Lanthimos, Jordan Peele and Francis Lee (‘all difficult,’ he reveals, with a smile that makes it clear this is a compliment), it is Glazer who remains his most influential mentor. ‘Working with Jonathan over the years was my film school. I’ve got one of the world’s best film directors telling me in detail why sound works on a particular shot. He’s the most rigorous director I know. Down-to-earth, but a genius too.’

This article originally appeared in the Awards Journal. Pick up your free copy now in any Curzon cinema while stocks last.

WATCH THE ZONE OF INTEREST IN CINEMAS