There’s a lion, a bear, a leopard and a tiger. A teddy, a shell and even an apricot. International film festival prizes come in all shapes and sizes: animals, fruits and any manner of inanimate objects. But the one prize to rule them all is the Palme d’Or, the Golden Palm. The top award at the Cannes International Film Festival is the most prestigious in film. (Sorry Oscar, more people might know who you are, and you might guarantee a larger box office, but when it comes to prestige you’ll always be a runner up to Cannes.)

Over the years, some of the most universally acclaimed films have received the Palme d’Or. A few choices have been odd, a number controversial. But for the most part, the winners represent the cream of world cinema’s crop. Gathered here, in chronological order, are 25 of the most significant, popular, controversial and leftfield winners. We leave it to you to decide which is most deserving of the top spot – the Palme d’Or of Palmes d’Or.

25 The Third Man (1949)

It wasn’t the first winner. The festival had three previous editions, in 1939 and after the end of World War II, in 1946 and 1947. But the 1939 prize – which went to Cecil B DeMille’s Union Pacific – was only announced retrospectively in 2002, while the other two editions generously shared prizes among a variety of films. However, Carol Reed’s stunning Vienna-set thriller, which finds Joseph Cotten’s writer searching for an old friend played with more than a little charisma by Orson Welles, didn’t even win a Palme d’Or. Until 1954, the top prize at the festival was known as the Grand Prix du Festival International du Film. (It would return to that title for a brief period between 1964 and 1974.) Nevertheless, The Third Man walked away with the highest prize. It has also been voted the greatest British film and is arguably the finest film noir made outside the US.

24 Marty (1955)

The first film to win the renamed Palme d’Or is actually a remake. It had previously been filmed in 1953 as part of the Philco Television Playhouse series for US TV. It starred Rod Steiger in the title role. It was directed by Delbert Mann, who would also direct Ernest Borgnine in this far better known feature version. Written by Paddy Chayefsky, who would later pen the lacerating media satire Network (1976), it told the story of a lonely woman looking for love. It captured a mood for a more realistic kind of drama – even if that style now looks dated. The film also won four Oscars, for Chayefsky, Mann, Borgnine and Best Picture. It would be 55 years before any film equalled Marty’s award success on both sides of the Atlantic.

23 La Dolce Vita (1960)

1960 was a radical year for cinema. Jean-Luc Godard had unveiled his revolutionary feature debut À bout de souffle (Breathless) at the Berlin Film Festival, where he was awarded Best Director. Then, in Cannes, there was an Italian cinematic duel between the wild, carnivalesque world of Federico Fellini and the more measured, oblique strategies of Michelangelo Antonioni. The latter’s L’Avventura divided critics and audiences alike, and on the closing night, he had to console himself with the Jury Prize. (Shared with Kon Ichikawa’s Odd Obsession.) Fellini became the toast of the 13th edition, with his satire of Rome’s beau monde and its coruscating portrait of economic inequality in a country that was experiencing its first boom since the end of World War II. It was also the first Fellini film to star Marcello Mastroianni, who would come to be seen as the director’s on-screen alter-ego.

22 The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

One of only three musicals to win the Palme d’Or (Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz shared the title with Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha in 1980, and Lars von Trier scored two decades later with Dancer in the Dark), Jacques Demy’s gorgeous, glorious drama nodded towards but was also wildly different to the classical Hollywood musical. No less vibrant or colourful than its US counterparts, the film unfolds within the banal environment of a small French coastal town. It tells of a love affair between a young woman who works in an umbrella boutique and a handsome car mechanic. The dialogue is sung rather than spoken, giving the film an otherworldly quality. It’s made all the more magical with the presence of Catherine Deneuve, in her breakthrough role.

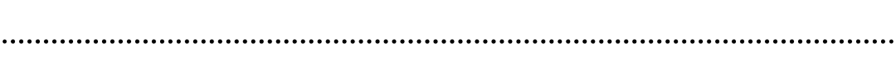

21 Blow-Up (1967)

Antonioni might have been smarting from not winning Cannes’ top prize in 1960, but his portrait of Swinging Sixties London finally bagged it for him. Many would argue that it is a lesser film than his four brilliant and radical previous features (L’Avventura, 1961’s La Notte, 1962’s L’Eclisse and 1964’s The Red Desert, which remains one of cinema’s boldest experiments with colour). It’s arguably not his greatest English-language feature either. (That would be his collaboration with Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider on 1975’s The Passenger.) But as a portrait of a moment in time, it captures the hedonistic atmosphere of the late 1960s. And the murder that might or might not have been captured by David Hemming’s fashion photographer presages the era’s tilt towards a darker period as the 1970s approached.

20 If.... (1969)

France was in the grip of student and worker demonstrations in 1968. It culminated with huge disruption throughout the country in May, just as the festival was opening on the French Riviera. Filmmakers actually brought that edition to a premature close, out of respect for the demonstrators and in anger at the French government’s decision to sack legendary archivist and programmer Henri Langlois from his position as head of Paris’ Cinémathèque Française. So, when the festival reconvened the next year, Lindsay Anderson’s portrait of rebellion and revolution must have struck a chord with the jury. Inspired by Jean Vigo’s acclaimed short Zéro de conduite (1933), If…. drew a generational line between the ills of traditionalism and the hopes of modernity in British society. It remains one of the most popular British films ever made.

19 Taxi Driver (1976)

The Cannes Film Festival has often embraced controversy, but it’s normally present following a screening – by a dissatisfied audience, or during a press conference. Only on rare occasions is a public controversy caused by the disagreement between jury members. However, that’s what happened when jury president Tennessee Williams realised he was in a minority against Martin Scorsese’s dazzling and visceral 'dark night of the soul' winning the top prize. A playwright known for the emotional violence of his work, he was left aghast at the physical violence that explodes in the climax of Taxi Driver, as Robert De Niro’s Vietnam vet Travis Bickle finally cracks and goes on a killing rampage, ostensibly to save Jodie Foster’s underage prostitute. The combination of Paul Schrader’s bleak screenplay, Scorsese’s artistry, Bernard Hermann’s final score and an extraordinary cast turned a taut psychological thriller into a barometer of the political climate of the US during the 1970s. The film didn’t carry its Cannes success over to the Academy Awards. It was nominated for Best Picture but lost out to the softer edged Rocky. (Bizarrely, Scorsese didn’t even receive a Best Director nomination.)

18 Apocalypse Now (1979)

Francis Ford Coppola’s dazzling Vietnam drama shared the top prize with Volker Schlöndorff’s powerful adaptation of Günter Grass’ The Tin Drum. The win gave Cannes some symmetry across the decade, which began with M*A*S*H – a Korea-set satire that was clearly all about Vietnam – winning the Palme d’Or in 1970. But where Robert Altman’s film was salty and grounded in an everyday world, Apocalypse Now was a fevered dream unfolding across an epic canvas. The film wasn’t even completed when it played at the festival, but its brilliance swayed the jury. (Although jury president Françoise Sagan later complained that there was undue pressure to reward Coppola – who had previously won the prize for The Conversation in 1974 – against what she thought should be an easy win for Schlöndorff, hence the award split.)

17 Paris, Texas (1984)

There were a few stunning films that won a Palme d’Or in the 1980s. They include Andrzej Wajda’s Man of Iron in 1981, Yılmaz Güney and Şerif Gören’s Yol in 1982 (shared with Costa Gavras’ Missing), Shohei Imamura’s devastating The Ballad of Narayama in 1983 and Maurice Pialat’s Under the Sun of Satan in 1987. But none are quite as haunting or majestic as Paris, Texas, Wim Wenders’ collaboration with Sam Shepard. (That said, Imamura’s exquisite yet unsentimental fable comes close.) From the emergence of Harry Dean Stanton’s Travis, out of a desert, at the beginning of the film, through to his moving confessional at the end, Wenders’ drama is a compelling portrait of a man lost and adrift in the contemporary US. And if there is ever a list compiled of the greatest scores to Palme d’Or winners – or even the wider list of all Cannes competition entries – Ry Cooder’s richly atmospheric soundtrack must surely come close to the top.

16 Sex, Lies and Videotape (1989)

Spike Lee wasn’t happy. His riveting, angst-driven portrait of racial division in the US, Do the Right Thing, lost out to a drama in which the main protagonist masturbates to interviews he’s conducted with women talking about their sex lives. That’s a somewhat simplistic summary of Steven Soderbergh’s intelligent drama, which explores contemporary mores and relationships and came to represent a new era in US indie cinema. It’s lost little of its power over the last three decades, remaining a piercing portrait of the games we play to get what we want. And Cannes Best Actor winner James Spader is magnetic. As for Lee, what really irked him was finding out that jury president Wim Wenders felt Do the Right Thing’s lead character Mookie – played by the filmmaker – was ‘unheroic’. It didn’t end up being a good awards year for Lee. Not only was his film not nominated at the Academy Awards, but the best prize went to the anachronistic race-relations drama Driving Miss Daisy.

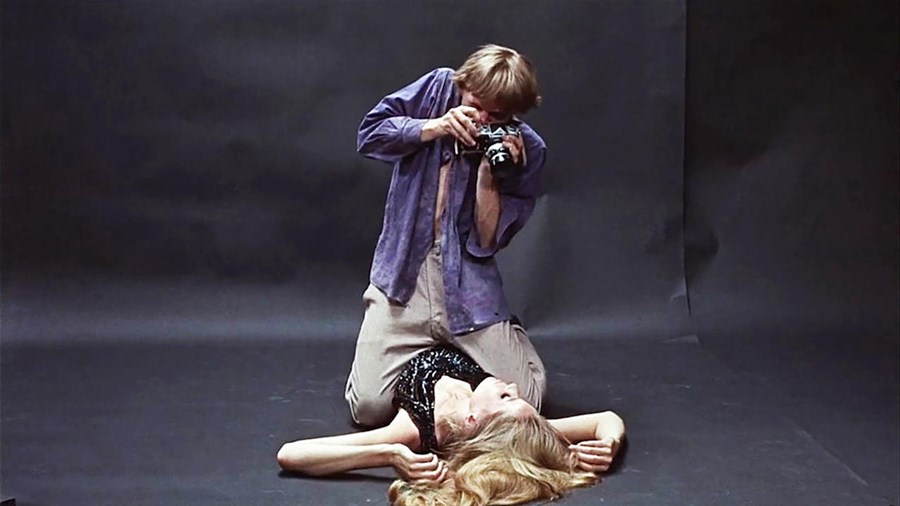

15 Wild at Heart (1990)

There was definitely a sense when Wild at Heart screened at the 43rd edition that it wasn’t David Lynch’s best. A section of the audience even made their feelings heard by booing the film at its premiere. (Not that uncommon a reaction at the festival.) But it came as a complete shock to some when the filmmaker’s ultra-violent fantasy noir was announced the winner of the main competition. Were the jury belatedly acknowledging the brilliance of Lynch’s 1986 masterpiece Blue Velvet? And was the same trick repeated the following year when the Coen brothers were awarded the Palme d’Or for Barton Fink when the finest of their early films, Miller’s Crossing (1990), had not received the credit it deserved? Barton Fink is rightly regarded as one of the Coens' most impressive films, so perhaps not. But Wild at Heart remains divisive, skirting the line between wild satire and indulgent self-parody.

14 The Piano (1993)

Finally! It only took 46 editions, but with the rapturous The Piano Jane Campion became the first female director to win the Palme d’Or. The film shared the accolade with Kaige Chen’s Farewell My Concubine. (The first Chinese film to win the award.) Holly Hunter won the Best Actress award (which she repeated at the Academy Awards, along with co-star Anna Paquin winning Best Supporting Actress and Campion Best Original Screenplay.) It’s not hard to see why it won. Not only is the film beautifully performed, designed, shot and scored (Michael Nyman at his best), but it also combines a powerful study of sexuality and patriarchy within the framework of a taut period drama.

13 Pulp Fiction (1994)

It’s impossible not to look back on the cinema of the 1990s without acknowledging the seismic impact Quentin Tarantino had upon it. Even if someone hasn’t watched one of his films, it’s hard to imagine that they haven’t seen at least one film made in the last 25 years that hasn’t in some way been influenced by him. And it was Pulp Fiction that defined him and made ‘Tarantino-esque’ a brand, style and even attitude. With its temporally fractured narrative, pop-culture references, iconic sequences and too-cool-for-cats swagger, as well as a knack for resuscitating previously moribund careers, it’s easy to believe that Tarantino’s sophomore feature was a shoo-in for Cannes’ top prize. But it was up against career-best work by Krzysztof Kieślowski, Abbas Kiarostami (who would win three years later with Taste of Cherry), Atom Egoyan and Patrice Chéreau. No mean feat for a director who was relatively unknown just a few years earlier.

12 Eternity and a Day (1998)

Greek filmmaker Theo Angelopoulos’ portrait of conflict and migration on the border of Europe feels more relevant with each passing year. His Cannes win was a long time coming. In 1975, he directed one of the towering achievements of European cinema with the 230-minute epic The Travelling Players. It cemented his reputation, which would continue to grow over the next 20 years. Many believed he would win the award in 1995 for Ulysses’ Gaze a potent combination of Balkans film history, a chronicle of the region’s turbulent journey through the 20th century and a searing portrait of the recent conflict, culminating in footage shot in a besieged Sarajevo. Instead, the Palme d’Or went to Emir Kusturica (for a second time after his win in 1985 for When Father Was Away on Business) and his magical-realist satire Underground. Angelopoulos was reportedly unhappy with the result, as were others who were uneasy with Kusturica’s politics. But the prize for Eternity and a Day was no consolation. It’s a powerful drama featuring a stunning central performance by Bruno Ganz.

11 Rosetta (1999)

Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne had been making documentaries since the late 1970s and feature films since the late 1980s. But with their 1996 feature The Promise they cemented a kind of filmmaking that would come to define them – a vérité approach to lives on the margins of society. Rosetta, featuring a breathtaking performance by Best Actress winner Émilie Dequenne, was the film that launched the filmmaking siblings onto the world stage. It was a raw and uncompromising account of poverty but evinced the skill of the writer-directors when it came to drawing both our ire and sympathy with no recourse to sentimentality. They would win again in 2005 with the equally emotive The Child.

10 Dancer in the Dark (2000)

Topping the list of Marmite Palme d’Or winners is Lars von Trier’s downbeat musical. Set in the industrial heartland of the US during the 1960s, it tells the story of Selma, a Czech immigrant who is losing her sight and finds herself charged with murder. Edgily shot, with music by Björk, who also plays Selma (she received the Best Actress award), the film features song and dance numbers in everyday settings. It’s perhaps a nod to The Umbrellas of Cherbourg whose star, Catherine Deneuve, plays Selma’s best friend. (The film also features Joel Grey, who was Emcee in the original Broadway production of Cabaret and Bob Fosse’s Oscar-winning 1972 film adaptation.) But von Trier’s nihilistic worldview and his stripping away the gloss normally associated with the musical genre didn’t win everyone over. Unsurprisingly, there were boos from the audience.

9 Elephant (2003)

Cannes had already taken a stance on US gun culture in 2003 when the 55th edition Special Prize was given to Michael Moore for his excoriating 2002 documentary Bowling for Columbine. Gus van Sant’s film marked a change in direction from the naturalistic dramas he had made in the 1990s. He experimented with an improvised docudrama style with his previous feature Gerry (2002). Elephant took the idea further. Inspired by Alan Clarke’s identically titled 1989 film, which detailed sectarian violence in Northern Ireland through a series of long tracking shots that each end with a killing. Van Sant employed that style in a recreation of the 1999 Columbine High School Massacre. At the same time, he delivers a poignant study of teen life and a chilling portrait of adolescent angst.

8 Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004)

Michael Moore’s film was not the first documentary to win the Palme d’Or. The Silent World, an exploration of life in the oceans directed by Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle, won in 1956. But Moore’s film remains one of the most politically incendiary winners. It chimed with a rising tide of opposition to the conflict in Iraq. And it offered further proof, if any were necessary, that Moore is a gifted filmmaker.

7 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007)

Cristian Mungiu’s popular win wasn’t the first time the loose group of filmmaking talent described by critics as the Romanian New Wave made a splash at Cannes. At the 2006 edition, Cristi Puiu's The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu, Cătălin Mitulescu's The Way I Spent the End of the World and Corneliu Porumboiu's 12:08 East of Bucharest all walked away with an award. But 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days winning the top prize became the crystalising moment. Like many of the films coming out of Romania at the time, Mungiu’s film comprises long takes, embraces realism, unfolds in a minimalist manner and is bitterly satirical. The story of a woman seeking a backstreet abortion for her friend in 1980s Bucharest, the film is uncompromising. And yet, within this bleak world, Mungiu has created a drama that is moving and occasionally funny, even as his critique of Nicolae Ceaușescu's totalitarian regime remains unswerving.

6 The White Ribbon (2009)

There are some directors for whom the Cannes Film Festival is a second home. Michael Haneke exists at the heart of his group. Since he emerged onto the world stage with Funny Games (1997), his brutal assault on the pernicious nature of what passes for ‘entertainment’ in the media, Haneke has been a constant at the festival. And he has won the Palme d’Or twice. In 2012, he picked it up for Amour. But his first win was for this unsettling portrait of life in a German village a year before the outbreak of World War I. Shot in lustrous black and white, the drama suggests that the country’s future has already been decided through the way that a new generation is defined by authoritarian rule. Even by Haneke’s high standards, The White Ribbon proved to be an outstanding film.

5 Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010)

Cinema as a sensual phantasmagoria, Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s blissful drama is not so easy a film to describe as it is one to fully immerse yourself in. The titular character is ill and nearing death. As he awaits the inevitable in his farmhouse in the middle of a rich and verdant jungle, Boonmee is visited by his dead wife and missing son, who has taken on a different form. Like all of Weerasethakul’s work, Uncle Boonmee is rich in metaphor and symbolism. But it’s the filmmaker’s languid pace and the enveloping nature of his drama that makes it so hypnotic. As the critic Sukhdev Sandhu noted, ‘It’s barely a film; more a floating world’.

4 The Tree of Life (2011)

A dream-like tone also permeated the following year’s Palme d’Or winner. Terrence Malick’s cherished project opens in the style of his 1973 feature debut Badlands, portraying life in 1950s rural US. It portrays a family dominated by a stern patriarch (Brad Pitt), a contrast to the loving mother (Jessica Chastain). These moments come from the memory of grown-up Jack, the eldest son, played by Sean Penn. Then, with little warning and only a subtle prompt spoken by Chastain’s character, we are sent spiralling back to the birth of the universe and the violent creation of Earth. The segment lasted 20 minutes and left some critics and audience members bewildered. There’s no denying Malick’s ambition in exploring the tension between nature and grace (a theme that he would delve into further with 2019’s A Hidden Life), but the film was not to everyone’s taste.

3 Blue is the Warmest Colour (2013)

A significant change recently took place in the main competition. In order to expand the range of award winners and to ‘share the love’, each film in the competition was only entitled to receive one award. That decision caused a problem for Steven Spielberg and his jury at the 66th edition. There seemed little doubt that Abdellatif Kechiche’s moving portrait of young love was the outstanding film of the competition. But much of its power derived from the performances of Léa Seydoux and Adèle Exarchopoulos. There was only one solution. In announcing the winner of the Palme d’Or, both Kechiche and his two leads were named winners. However, Blue is the Warmest Colour soon became mired in controversy. Jul Maroh, the graphic novelist whose work the film is adapted from, criticised the extended sex scene. And crew members complained about harassment from Kechiche on set. The two actors also stated that the filmmaker perhaps pushed them too far but have since softened their criticism. Kechiche has denied all allegations of wrongdoing.

2 I, Daniel Blake (2016)

Ken Loach received his second Palme d’Or – he won his first for the 2006 Irish drama The Wind That Shakes the Barley – for his anguished portrait of a man trapped within the Kafkaesque bureaucracy of the UK’s welfare benefits system. Dave Johns plays the titular character, who suffers from heart trouble and has been told by his cardiologist that he cannot do any physical labour. But a mandatory work capability assessment deems him fit and so his employment and support allowance is stopped. From there, he attempts to work his way through the labyrinthine appeals system, while also trying to give some help to Hayley Squires’ single mum. It’s an impassioned, angry film that gave voice to those struggling to make ends meet in a society that also sees the wealthy growing richer.

1 Parasite (2019)

Gross economic inequality is key to Bong Joon Ho’s popular satire. Not only was it the first film since 1955’s Marty to win both the Palme d’Or and Best Picture Academy Award, but it was also the first Korean film to do so. (And the first non-English-language film to take the top prize at the Oscars.) The Palme d’Or was just the first of many wins for a film that must have won more accolades at international festivals and awards ceremonies than perhaps any other. The key to its success is the universality of its tale – a clash between a poor and rich family that descends into chaos and a shocking finale. But there’s also Director Bong’s sly humour, present in all his work. And like Ken Loach’s film, Parasite touched a nerve.

Watch Palme d'Or winners on Curzon Home Cinema