Clarisse Loughrey pays tribute to the prolific, status quo-smashing director who, over the course of his many projects, always allows his signature style, and career-long thematic concerns, to shine through

No one breaks the rules quite like Taika Waititi. He locked horns with the Marvel Cinematic Universe – directing Thor: Ragnarok (2017) and Thor: Love and Thunder (2022) – and came out the other side without even a ding to his creative brand. Read through the Love and Thunder reviews and you’ll see, time and time again, it discussed firmly as a Waititi production, instead of a remotely operated Disney vehicle with any old director plonked down at the helm. And he’s a one-man ideas hub, busy spinning half of Hollywood’s plates without ever breaking a sweat.

Thor: Ragnarok (2017)

The breadth of his output is truly astonishing. In 2019, he won a screenplay Oscar for his World War II comedy Jojo Rabbit and directed several episodes of the Disney+ show The Mandalorian, all while voicing its monotone bounty-hunter droid IG-11. Since then, he’s cropped up as the goofy, tech-bro villain of Free Guy (2021), one of the sidekicks in Pixar’s Lightyear (2022) and made a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo in James Gunn’s The Suicide Squad (2021). He’s also collaborated with other directors and creators with the enthusiasm of someone trying to assemble the ultimate pop-culture supergroup. He directed several episodes of the FX vampire series What We Do in the Shadows – based on the 2014 mockumentary he co-directed with Jemaine Clement – as well as co-creating the Indigenous-teen show Reservation Dogs with Sterlin Harjo, and starring as Blackbeard in David Jenkins’ pirate comedy Our Flag Means Death.

What We Do in the Shadows (2014)

And, somehow, all of this – everything that he touches – remains distinctly Waititi-esque. It’s a style that’s easy to recognise, even if people aren’t all that used to defining what it actually is. That sometimes dark, always silly, New Zealand-sourced sense of humour is obviously key. Love and Thunder has a running joke about a pair of oversized goats who interrupt sincere moments with their panicked, fear-of-death screams. His colour palette, which often relies on the contrast between bright, primary shades, links back to his origins as a visual artist. He spent nearly a decade as a painter, at one point living in a commune in Berlin, before he broke into filmmaking with his Oscar-nominated short Two Cars, One Night (2003).

Thor: Love and Thunder (2022)

Waititi has, at various points, described his relationship with film as ‘an arranged marriage’. During a 2010 TED Talk, he even took issue with being called a ‘filmmaker’. ‘That’s not my job,’ he said. ‘My job is to express myself.’ And there’s certainly a distinct purpose to his work, with all his gods and vampires merely functioning as vessels for a greater cause: the desperate, heartfelt search for a sense of place in the world. His characters are looking for family, even when their blood ties fail them. They’re looking for home, even when there’s nowhere left to run back to. And, most importantly, they’re looking for their own truth – to find themselves in a way that hasn’t been dictated by those around them.

In his pre-Waititi years, Thor mostly fretted over whether he was ‘worthy’ to wield his hammer Mjölnir and rule the realm of Asgard. But Ragnarok, then Love and Thunder, question what ‘worthy’ even means in the first place. What is Asgard? A place or its people? And what do we live for if not to improve the lives of others? The director’s best and most illuminating work is Boy (2010) – an autobiography in only the vaguest sense, not directly based on his life but shot partially in his own childhood home in Waihau Bay on New Zealand’s North Island.

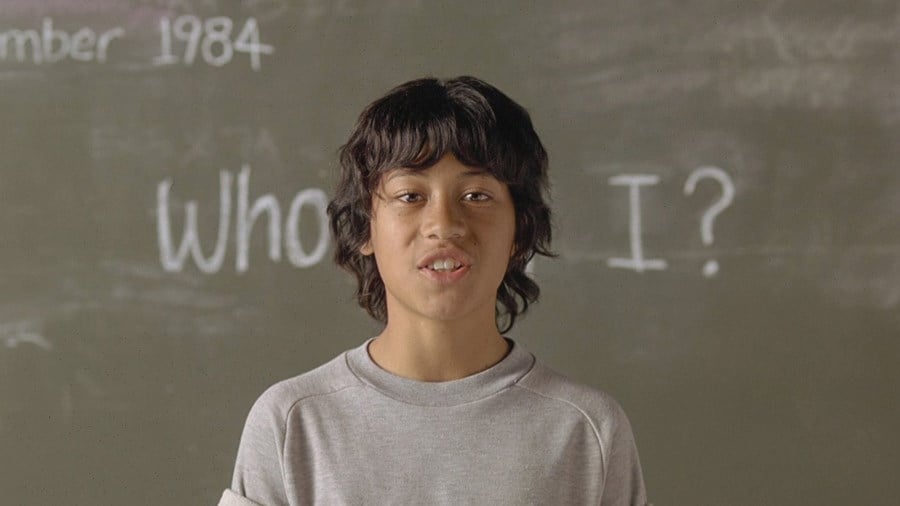

Boy (2010)

In his film, 11-year-old Boy (James Rolleston) is suddenly reunited with his estranged father, Alamein (Waititi). The kid has built up a near mythical image of Alamein in his absence, constructing strange fantasies about him as a deep-sea diver, captain of the rugby team, war hero, loving husband and parent. But, Boy, like so many of Waititi’s characters, is in for a rude awakening, as his daydreams are forced to reckon with the selfish, cowardly and, at times, violent man who’s now reentered his life. A man who won’t even let his own son call him ‘Dad’ because it ‘sounds weird’.

The concept of ideal masculinity, and ideal fathers, is really treated as one big chimaera in Waititi’s work, in a way that partially critiques the ‘warrior’ stereotype that’s become attached to Māori culture. ‘I come from a country whose idea of masculinity is quite extreme,’ the director said in 2016. ‘And I've grown up around a lot of that energy, I've been part of that a lot. And it's very draining, it's quite tiring trying to be macho.’

Jojo Rabbit (2019)

But, in Jojo Rabbit, Waititi was able to directly transplant the same ideas onto fascist 1940s Germany. Johannes ‘Jojo Rabbit’ Betzler (Roman Griffin Davis) is so bitter about his father who’s gone missing on the Italian Front, and the way the other boys treat him as weak and cowardly, that he’s constructed his own fantastical ideal – a make-believe Führer (Waititi) who promises that, as long as he’s loyal, Jojo will always be cool. Even through this self-consciously childish lens, Waititi finds a precise and damning way to portray how fascist beliefs are so often rooted in insecurities and self-delusions. That’s what makes it all so frightening – how easily this hatred can be conjured up.

Thor: Ragnarok (2017)

Those pressures to conform poison several of Waititi’s male characters, even if the results are significantly less dramatic. In his debut, Eagle vs Shark (2007), mulleted nerd Jarrod (Clement) is desperate to live up to his dead brother Gordon (Waititi, again), ignorant of the fact Gordon’s status as the perfect son is the very thing that drove him to suicide. In Hunt for the Wilderpeople (2016), drug dealer Ricky Baker (Julian Dennison) preaches the ‘skux life’, fantasising his criminal career will end with either a drive-by or a Scarface-style shootout. That’s an easier path to tread than the reality in front of him, that of an unwanted foster kid bouncing from home to home, stuck in a perpetual cycle of loss. By contrast, the women of Waititi’s films rarely have the luxury of self-delusion. They know exactly how and why the world has screwed them over: see Ragnarok’s deliciously corrupt Hela, played by Cate Blanchett, whose murderous impulses were happily exploited by her father Odin (Anthony Hopkins) before she was erased from Asgard’s history.

Jojo Rabbit (2019)

While concrete endings are a rare thing in Waititi’s work, he does reward those who can finally see the truth with a second shot – at family, at home, at personal freedom. In Jojo Rabbit’s final scene, we’re left with two kids, at the end of the war, holding onto a fragile hope that tomorrow can be a better place. In Hunt for the Wilderpeople, Ricky admits that he’s finally lost the impulse to run away. And, in Boy, Waititi’s protagonist sits at his mother’s gravesite, across from his father, and looks at him with a brand-new understanding. ‘The reality is: we’re all losers and we're all uncoordinated. We're the worst of all of the animals on Earth and there's something quite endearing about that,’ the director once said. And, as his films argue, only when we’re honest about our own imperfections can we truly find happiness.