In a world of fake news, where some believe journalism has reached its terminal point, the most fashionably unfashionable filmmaker pays tribute to the world of roving reporters.

The French Dispatch, whose offices are based in the sleepy Gallic town of Ennui-sur-Blasé, is an estimable publication run by American émigré Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray). Part of a Kansas-based newspaper, this colourful supplement covers everything from art and culture to politics and the vagaries of everyday life. It is also the focus of Wes Anderson’s eponymous tenth feature, and an homage to The New Yorker, the celebrated weekly magazine that began in 1925 and is now one of the most respected publications in the English language.

The French Dispatch (2021)

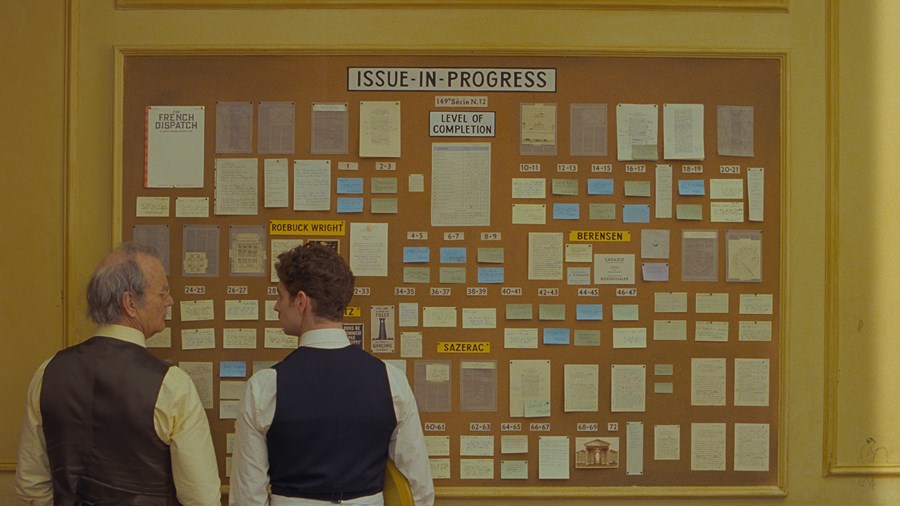

Wes Anderson’s film works as both a tribute to and pastiche of this world of journalism; not the ripped-from-the-headlines format of daily news, but considered, lengthy articles that take a wider view of their subject, and the world in general. Moreover, The French Dispatch loosely employs as its structure the format of The New Yorker. Between bookending sequences in the publication’s offices, the film is divided into one vignette and three main sections, each a story penned by the magazines’ most celebrated writers: Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson), J. K. L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton), Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand) and Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright).

The French Dispatch (2021)

The New Yorker was created by the husband and wife journalist team Harold Ross and Jane Grant. Whereas Grant found a job at The New York Times aged 16, remaining there for 15 years, Ross was a veteran hack whose early years saw him employed by a variety of newspapers across the US. Grant became business and content consultant for The New Yorker, while Ross became its first editor. Together, they envisioned a magazine whose appeal would be specifically aimed at the residents of the city it was named after. E.B. White, one of the first star writers of the magazine, noted that Ross’ intentions were ‘more in contempt of what was being published than with any notion of how to improve it’. But gradually, the magazine took shape, increased in popularity and became one of the most widely admired publications in the US.

The French Dispatch (2021)

Ross wanted a magazine that offered readers sophistication and humour. It engaged with politics from a distance and, like New York, was predominantly centrist, with the scales shifting marginally left in more turbulent times. It embraced culture but abhorred the indulgence of celebrity. And it revelled in the richness of New York life, not only listing the must-see galleries, theatres, cinema screenings and talks, but the best culinary delights the city had to offer. Above all, the magazine championed – and continues to – the skill and wordsmithery of its writers; not just a staff of workaday reporters, but some of the greatest authors of their day, from E.B. and Katherine White to James Thurber, Dorothy Parker and Wolcott Gibbs. (For a detailed account of the magazine's inception and the colourful individuals who contributed to it, Thomas Vinciguerra's 'Cast of Characters' is an invaluable guide.)

Ross was known for his mantra ‘I’m firing you because you are not a genius’, underpinning his magazine’s high standards, but also his temperamental nature. Howitzer, Ross’ cinematic alter-ego, is equally demanding, but his principle rule, as written above the door to his office, deals more with his abhorrence of emotion: ‘No crying’. He’s not the only figure in the film to draw on The New Yorker’s illustrious past.

In the brief divertissement that follows the film’s prologue, Wilson’s Herbsaint Sazerac presents a portrait of life in Ennui-sur-Blasé. It’s an affectionate pastiche of the ‘Talk of the Town’ section that appears weekly in The New Yorker. Sazerac is a fictional version of Joseph Mitchell, who began writing for the magazine in 1933 and whose portraits of people and events, particularly in New York, were admired for their warm humanism and curiosity towards everyday life. (Mitchell remains best known for ‘Joe Gould’s Secret’, a two-part portrait of one of Manhattan’s more eccentric characters, written over a 20-year period.)

Anderson’s first ‘article’, ‘The Concrete Masterpiece’, details art critic J. K. L. Berensen’s account of the relationship between art dealer Julien Cadazio (Adrien Brody) and troubled artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro, with Tony Revolori playing him in his youth). The filmmaker drew on a six-part profile of legendary art dealer Joseph Duveen, written by S.N. Behrman, a successful Broadway playwright and long-term contributor to ‘The New Yorker’, which was first published between September and November 1951. As with the two subsequent parts of the film, the writer plays as central a role in the action as their subject. And Swinton, now a regular member of the filmmaker’s regular ensemble, successfully captures the affectations of a character whose desires are as driven by carnality as they are aesthetics.

The French Dispatch (2021)

‘Revisions to a Manifesto’ transposes the May 1968 riots in Paris to Ennui-sur-Blasé, where bourgeois student Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet) is leading a charge on behalf of the town’s younger generation to change the world through protest and action. His efforts are observed and recorded by veteran writer Lucinda Krementz, whose prose skills are also employed in pruning and improving Zeffirelli’s poorly written manifesto. Krementz is based on Mavis Gallant, a Paris-based Canadian short-story writer who ranks alongside John Cheever and John Updike as one of the most prolifically published fiction writers in the magazine's history. She also wrote non-fiction, most notably her two-part portrait of the demonstrations and riots in the French capital, ‘The Events in May: A Paris Notebook’. The style of the article, more conversational than hard reportage, is perfectly captured by McDormand, who portrays Krementz as a steely character with a soft spot for the idealism of youth.

The French Dispatch (2021)

The final story in The French Dispatch is arguably the film’s pièce de resistance: a witty encounter between rarefied journalist Roebuck Wright and Ennui-sur-Blasé’s famed police chef Lt Nescaffier (Stephen Park). The story is intercut with a pitch-perfect 1970s-era TV interview between a host (Liev Schreiber) and Wright. Taken together, Wright can be seen as an amalgam of acclaimed writer and gifted orator James Baldwin and one of The New Yorker’s most charismatic contributors A.J. Liebling, who was celebrated as much for his writing on food as his reporting during the Second World War. Jeffrey Wright balances the intensity of his character’s intelligence with a slight hauteur, which becomes more pronounced as the crime that interrupts his much-anticipated meal becomes increasingly – and typically, in an Anderson film – frenetic.

The French Dispatch (2021)

References to actual figures notwithstanding, The French Dispatch is no biographical portrait. (It’s as realistic an account of the lives of journalists as the filmmaker’s 2004 comedy The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou was a faithful account of the exploits of marine adventurer Jacques Cousteau.) Every element in this world is filtered through Anderson’s singular vision – one that has as many critics as it does devotees. Stylistically, it is of a piece with his most recent live-action features The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) and Moonrise Kingdom (2012). But where some of Anderson’s previous films saw aesthetics eclipsing emotions, here he achieves a perfect balance. His affection for this world of writers is as close to passionate as any of his films have achieved. And just like the covers that The New Yorker is famed for, The French Dispatch gives us an artist’s impression of the world – one that romanticises as much as it parodies.

The French Dispatch is in Cinemas from Friday