Lillian Crawford considers how Wim Wenders’ gentle, Oscar-nominated drama extols the power of architecture, and continues his fascination with capturing artwork on film.

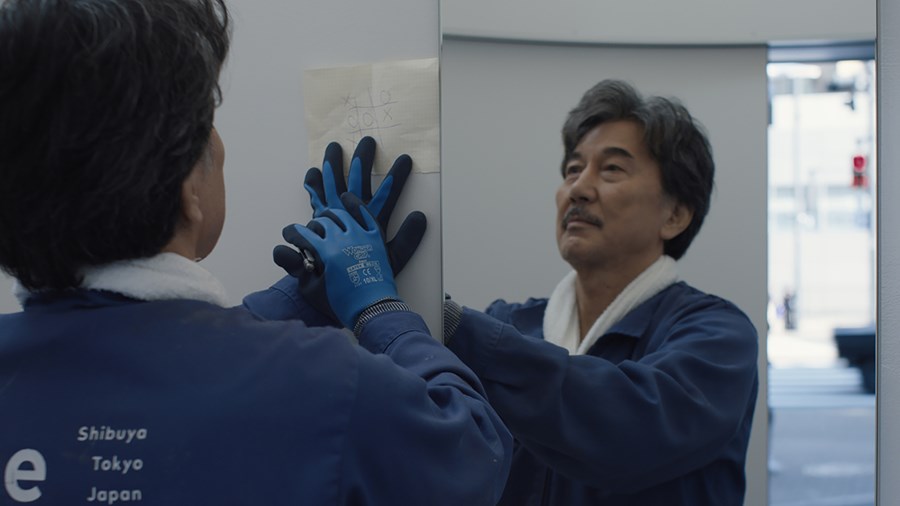

At the forefront of the website for The Tokyo Toilet, a project in which 16 architects create unique and bespoke public lavatories across 17 locations, is ‘Maintenance’. Click on the page and you will see footage of cleaners at work, face masks, plastic gloves and blue overalls on as they delicately polish every inch of every cubicle. ‘The Tokyo Toilet is not only about designing new facilities,’ it reads, ‘it is also about organising all aspects of the project so that the facilities can be maintained well and used comfortably by everyone.’

It is an egalitarian project – everyone regardless of class has to go to the loo – that provides free access to a simple service, housed within beautiful works of art. It has something in common with the work of Wim Wenders, not least his 3D art documentaries Pina (2011), about choreographer Pina Bausch, and Anselm (2023), about artist Anselm Kiefer. These films take localised art and bring it to the world through cinema. But it is about more than making art accessible, in the mode of ‘Exhibition On Screen’ or live-stream ballet performance; Wenders reconfigures the artworks into a whole new creation.

Perfect Days (2023)

Perfect Days came about after Wenders was invited to make a series of short films inspired by The Tokyo Toilet. There is the potential for a 3D documentary here, moving through the spaces of these lavatories as mere recreation for those unable to visit them in Japan. But far more compelling to Wenders is the story of those employed to maintain these sites not simply as functioning, hygienic public loos, but as artworks. Reading the details about cleaning on the project’s website reveals the rigorous routine involved, and the various strata of inspection required.

It has a meditative quality. By contrast to the Western functionalism of lavatories, in Japan they offer spaces of respite and solace from the world. The walls of the lavatory designed by Shigeru Ban are huge translucent coloured glass panels; however, when locked, the exterior glass turns opaque. Toyo Ito’s design consists of three mushroom-shaped buildings resembling the fungi that sprouted from the forest surrounding Yoyogi-Hachiman shrine. Each cubicle is a sanctuary, echoing the spiritual qualities of Shibuya, Tokyo. Where some find public lavatories a space of anxiety or danger, the architects have strived to create small spaces of calm in the urban landscape.

Rather than segmenting the lavatories into individual short films, Wenders unifies them in his feature Perfect Days through the maintenance worker Hirayama, played by Koji Yakusho. He is, unlike his younger colleague Takashi (Tokio Emoto), deeply sensitive to the architecture of the buildings, shown through his love of photography, plants and Western popular music such as Lou Reed and Patti Smith, which he still listens to on cassette. Everything in his life is tactile and analogue, juxtaposing with the futuristic technology employed in many of the loos themselves. Indeed, the style of several of the buildings he cleans stands in stark contrast to the simplicity of Hirayama’s own home.

Wenders first went to Japan in 1977 to watch films directed by Yasujirō Ozu at the Japanese Film Institute. Watching without subtitles, Wenders was steeped in Ozu’s visual language, and in 1983 he shot a documentary called Tokyo-Ga tracing the locations of Ozu’s films. Critic Noël Burch coined the term ‘pillow shot’ to describe the moments in Ozu’s films when the image breaks away from the story to simply show the setting, held for several seconds of landscape and object. The lavatories in Perfect Days function in this way, often held in frame for extended periods of time, simply watching people coming and going, and seeing how the buildings change over the course of the day, and from one day to the next. It lends an air of poetry to the film, and serves as a cinematic caesura to prevent it from ever getting carried away by the tide of narrative flow.

Perfect Days (2023)

These pillow shots echo a number of directors’ interest in the characterisation of buildings and public works, from Hitchock’s Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired Vandamm house in North By Northwest (1959) to the watchful documentaries of Frederick Wiseman. In Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle (1958) and PlayTime (1967), the modernist house and cityscape framed in wide shot become the site of intricate visual comedy, watching the details of architecture and how people interact with it. And the house in Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite (2019), the large glass windows, open staircases and ultra-modern tech become the stage for both the comic and horrific. The designs in Perfect Days are kept at a level of serenity, although there is always the sense that something could soil the immaculate canvas they collectively create.

The spiritual cousin of Perfect Days is Koganada’s Columbus (2017), the ‘Mecca’ of modernist architecture in Indiana. The film centres on two young people, played by John Cho and Haley Lu Richardson, as they walk through the city and discuss the buildings around them, including works by Eliel and Eero Saarinen, I.M. Pei and James Polshek. ‘He had this idea, Polshek did, of architecture being this sort of healing art. That it had the power to restore and that architects should be responsible,’ remarks Cho’s character. Wenders made Perfect Days in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, and felt inspired by the attempts of the architects who worked on The Tokyo Toilet to create a means of bringing people together through the shared use of the public lavatory. There is an affinity between the churches and libraries of Columbus, and the humble loos of Tokyo.

Columbus (2017)

Perfect Days is punctuated by a visual motif of leaves in the wind, with the sun creating a form of shadow play. These are called ‘komorebi’ in Japanese, representing a moment of epiphany for Hirayama that led him to work in these public loos. There is something deeply comforting about watching someone’s daily routine in a film – taken to its extreme in a film like Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975) – but also an anxiety when even the slightest change is made. The Tokyo Toilet website describes the reason for their commitment to the highest quality maintenance is that, ‘people find it hard to spoil something that has been carefully cleaned’. It is a project, and a film, that believes in the common decency of humanity.

WATCH PERFECT DAYS IN CINEMAS