As Jordan Peele grapples with themes of filmmaking spectacle in his latest horror movie, Leila Latif looks at the lengths performers have gone to for our entertainment since the birth of cinema – from Buster Keaton to Tom Cruise and beyond.

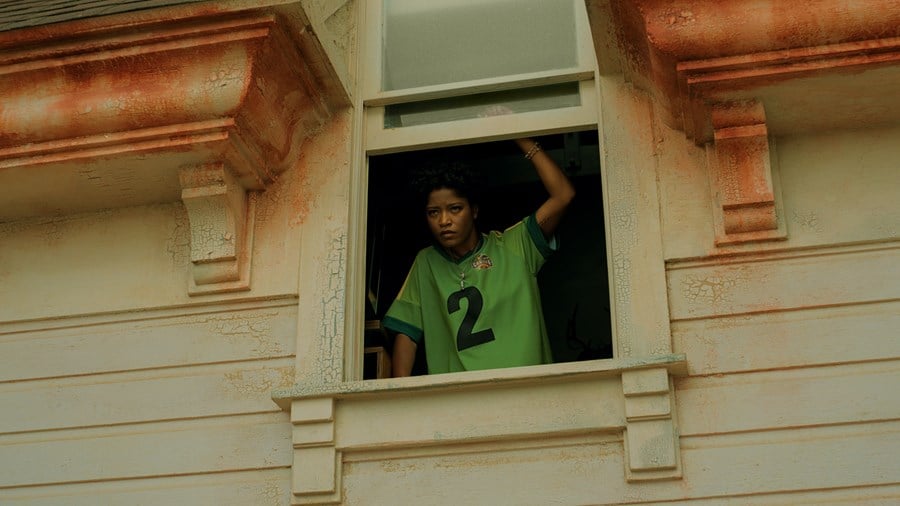

When we first meet Emerald Haywood (Keke Palmer) in Jordan Peele’s Nope, she strides onto a film set and explains that her family are descendants of the jockey who appeared in Eadweard Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion (1887), ‘the very first assembly of photographs used to create a motion picture’. She ends her speech with a knowing grin and a spin. ‘From the moment pictures could move,’ she declares, ‘we had skin in the game!’ To claim any one single interpretation of Peele’s magnificent new blockbuster would do a disservice to one of Hollywood’s most exciting, and consistent, directors. But the film – part-creature feature, part-Spielberg love letter, part-UFO spectacle – is also a fascinating look at how, from the moment pictures could move, Hollywood would never run short of people willing to sacrifice their own skin for cinema.

Nope (2022)

As the medium moved from a few seconds of horses galloping into the longer form narratives of the silent era, Buster Keaton emerged as one of its earliest stars. Having grown up on the Vaudeville stage, he was a seasoned performer by the time he made his screen debut at age 22, where his star power and stunts proved legendary. He defied death with his mind-blowing feats, standing stoically as a house collapses around him in Steamboat Bill (1928), running a speeding train into a river in The General (1926) and leaping between buildings in The Three Ages (1923). Despite his prowess, he was often horrifically injured and nearly drowned on several occasions. He would joke that he had broken ‘every bone in his body’ by the end of his life – he even snapped his neck during a water-tank stunt in Sherlock Jr (1924). Such danger in the silent era was not limited to Keaton’s stunts. Character actor Lon Chaney, best remembered for his portrayals of The Phantom and Quasimodo, also suffered for his art. In addition to skilfully applying his own make-up, the performer would wrench back his nose with painful wires to transform his face for roles, and permanently damaged his sight with false glass eyes.

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

As film images grew crisper, there were still those willing to risk their lives to commit the perfect image to celluloid. One of the most brilliant but foolhardy visionaries Howard Hughes showed as much with his 1930 war epic Hell’s Angels. The film involved many scenes of planes dogfighting, which were performed by 137 pilots. Three of those aviators and a mechanic died during the production, and when Hughes piloted an aircraft for a stunt everyone else considered too dangerous, they were proved right. He fell out of the plane, fractured his skull and needed extensive reconstructive surgery on his face.

The filmmakers of the New Hollywood renaissance, which began in the late 1960s and extended into the early Eighties, were just as trigger-happy as their predecessors. Auteurs of the period like Polanski, Kubrick and Coppola famously traumatised their casts and crews with endless takes, unsafe working conditions and, in some cases, permanent injury. One of the most famous examples of this occurred on the Philippines set of Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). The filmmaker insisted that a 320-ton steamship be manually transported over a hill, a manoeuvre that injured six crew members, and ordered unsafe shoots where local extras were injured and killed. Apocalypse Now not only nearly broke Coppola, but literally gave 36-year-old Martin Sheen a heart attack.

Apocalypse Now (1979)

Towards the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, health-and-safety standards had doubtless improved. Nowadays, stunt professionals with fastidious regulations became a normal presence on film sets, but the danger never truly went away for those committed to pushing boundaries. Tom Cruise, famous for performing all his own stunts, has created movie magic hanging out of planes and scaling the Burj Khalifa for the Mission: Impossible franchise. There are still (quite literal) missteps despite the safety protocols: in Fallout (2018), we see the moment the actor’s ankle shatters as he lands incorrectly when leaping between tower blocks. Also in 2018, footage emerged of Uma Thurman crashing a faulty car in Kill Bill (2003), one that director Quentin Tarantino ensured her was safe. His reputation was damaged further when an interview resurfaced where he explains that, for a scene in Inglorious Basterds (2009), he persuaded Diane Kruger to let him strangle her with his own hands.

Mission: Impossible - Fallout (2018)

This danger is not unique to cinema. It was also keenly felt on the small screen thanks to the pioneering antics of the delightful daredevil Johnny Knoxville on his MTV reality stunt show Jackass at the turn of the millennium. Knoxville and his motley crew (including Steve-O, Bam Margera and Jason ‘Wee Man’ Acuña) revelled in the risks they were taking, gleefully laughing in the face of broken bones, concussions and lost teeth. Their joyful self-sacrifice in the name of comedy came just before the arrival of social media; when Facebook, Instagram and YouTube became popular, they spawned a generation of reckless, Jackass-primed attention seekers.

Jackass Number Two (2006)

In the 2010s, once filming yourself going about your day-to-day was normalised, the ‘challenge’ became commonplace, the internet full of users dumping buckets of ice water over their heads, choking on cinnamon or eating laundry-detergent pods. Those seeking to monetise these challenges took them to the extreme. Inspired by the Sandra Bullock movie Bird Box (2018), they drove their cars blindfolded or, more inexplicably, climbed precarious stacks of milk crates. Just like Buster Keaton a century prior, people were breaking their bones for our entertainment.

Bird Box (2018)

A strange nihilism emerged online, most typified by famed internet douche Logan Paul, who posted everything from tasering rats and setting his own furniture alight to filming victims of suicide for attention. This culminated in his 2021 televised ‘exhibition bout’ with the boxing World Champion Floyd Mayweather, where over a million people paid to watch a live feed of Paul being repeatedly punched by the athlete. But Paul was not alone in putting his body on the line for highly profitable content; amateur climbers Vitaliy Raskalov and Vadim Makhorov, for example, ascended to the top of the 632m Shanghai Tower without safety equipment. The GoPro footage of their antics surpassed 73 million views and landed them corporate sponsorship deals with brands like North Face. This foolhardy attitude dominates among those hunting down internet fame. The numbers of people who get injured or die in pursuit of engagement is staggering: they fall off buildings, drown mid-selfie and plummet into ravines in their desperation for ever more clicks.

Nope (2022)

So Nope, while being a glorious puzzle box, is also in many ways a document of the ultimate clash between modern influencer-driven ambition and the success-at-any-cost attitude from the advent of cinema. Without giving away any of its mysteries, much of the film’s plot stems from an innate desire to capture spectacle. The core characters – an acclaimed cinematographer, a conspiracy-loving tech expert, a traumatised former child star, a TMZ paparazzo and a pair of Hollywood horse trainers – are all driven to get that one ‘perfect’ shot. As the film’s Bible-quote title card tells us: ‘I will cast abominable filth upon you, make you vile and make you a spectacle.’ Jordan Peele’s latest taps into a dark desire of filmmaking spectacle that has existed since the 19th century. And if bones need to crunch, blood needs to pour from the sky and valleys need to be filled with a chorus of blood-curdling screams to achieve that spectacle, so be it.

WATCH NOPE IN CINEMAS