Mark Cousins ruminates on the idea of the auteur producer in light of his recent film on the legendary British producer, The Storms of Jeremy Thomas.

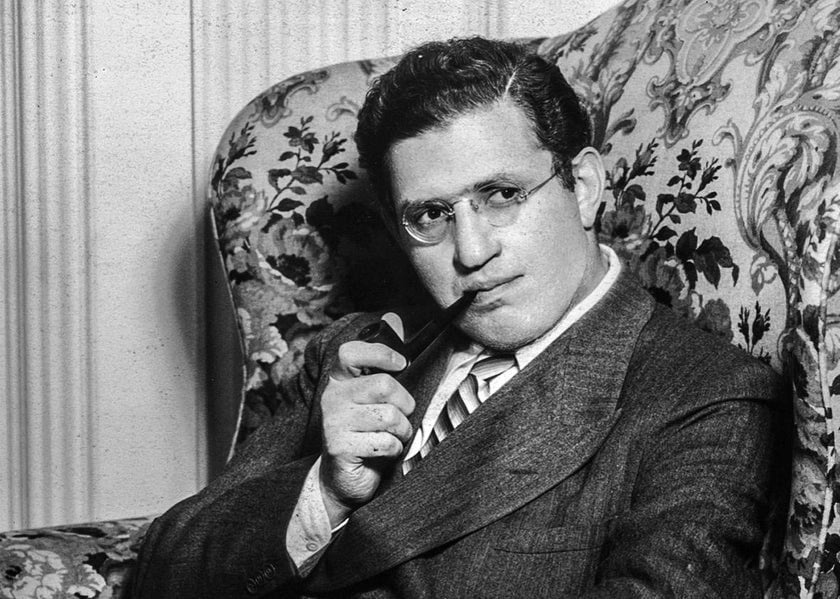

We’re all familiar with the idea of auteur filmmakers — people like Ingmar Bergman or Jane Campion, whose themes, images and worldview seem to flavour or steer all their films. But what about auteur producers? Are there such people? There’s no doubting the quality and impact of the films produced by Darryl F Zanuck, but The Grapes of Wrath (1940), All About Eve (1950), The King and I (1956) and The Longest Day (1962) are such different worlds, tones and levels of seriousness that it’s hard to see connections.

Darryl F. Zanuck (© The Life Images Collection/Getty Images)

In Europe, the great Marin Karmitz has produced films for Abbas Kiarostami, Krzysztof Kieslowski, Alain Resnais, Yilmaz Guney, Agnes Varda, Michael Haneke and Jean-Luc Godard — a stellar list of auteurs with wildly diverging visions. The only common thread is a commitment to cultural cinema. Of course in Hollywood, there were producer-directors like Billy Wilder and Frank Capra, but even Wilder didn’t steer us in a single direction.

Further back in film history, we find more intriguing candidates for auteur producer status. Mary Pickford, for example. Sometimes uncredited, she produced 35 films, including many of her best. Of course, the fact that she was also a star in her films complicated the idea of authorship, as by producing she was also managing her star image. But there are distinctive optics in them — a fresh, youthful early 20th Century sense of storytelling and adventure. Pickford’s fellow Canadian, Nell Shipman, produced at least nine films between 1920 and 1947, and directed some of them too. Most of the films were about outdoorsy women and/or cars and animals: she was a plein air adventurer.

Mary Pickford (© Getty Images)

After Shipman came the now better-known producers such as precocious MGM supremo Irving Thalberg, who, in Grand Hotel (1932), Red Dust (1932), Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) and Camille (1936) forced through the distractions of commerce and marked a sophisticated sense of what the star system was, and why script quality mattered.

Still, Mata Hari (1931) and A Day at the Races (1937) — both produced by Thalberg — are very far apart. More coherent was the career of a definite auteur producer David O. Selznick. Famed for his exhaustive memos, again and again, he launched prestige female-centred films veneered with literary-romantic finishes. The fact that Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) feels more Selznick than Hitch shows how strongly his hand was on the aesthetic tiller. In a later era, producer Roger Corman also drove and flavoured his productions, tailoring them to the market and often insisting that there should be sex or violence every six to eight pages or so, but otherwise allowing (or encouraging) progressive social ideas to filter through such a fixed grid.

David O. Selznick (© Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

I’ve just made a film about one of Britain’s greatest auteur producers, Jeremy Thomas, but before I started this article, I asked him who, for him, were his great predecessors. He mentioned two. The first was Serge Silberman, who started with a bang in 1956 with Jean-Pierre Melville’s chiselled heist masterpiece Bob le Flambeur. From there, it was uphill a lot of the way for Silberman, mostly in lockstep with Luis Buñuel, with whom he made Diary of a Chambermaid (1964), The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) and many more, before going on to produce Kurosawa’s Ran (1985) and Oshima’s Max, Mon Amour (986). And when you look at the list, Jeremy is right. There’s nothing too homey or easy in his filmography. Each movie discomforts, like a stone in your shoe.

Thomas’s second choice is Saul Zaentz, whose resume includes One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Amadeus (1984), The English Patient (1996), The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988) and The Mosquito Coast (1986). Are there common themes and approaches in them? Perhaps, yes; a cautious romanticism, a soaring interest in intelligence?

Zaentz was clearly a vastly significant figure, but Jeremy himself is closer to Silberman, I think. Zaentz might have done The Last Emperor (1987), but films like Crash (1996), Eureka (1982), Bad Timing (1980), Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence (1982), Sexy Beast (2000), Tale of Tales (2015), 13 Assassins (2010), Naked Lunch (1991) and The Shout (1978) come from a darker place.

The Storms of Jeremy Thomas (2021)

What is that darker place? As he and I drove down France on our way to the Cannes Film Festival, Jeremy called it ‘the secret box in my head’. He meant the place where our uncensored (perhaps unacknowledged) desires are. Our deep sexual feelings, our rage, desire to hurt or smash or — mostly — to transgress. Again and again, Jeremy’s films open that secret box. They acknowledge the un-acknowledged. In our film, Tilda [Swinton] calls him a pirate, and that’s a good metaphor, I think. He sails the high seas, steers into the storm, doesn’t tack into safe or shallow waters. He sought out Takeshi Miike and his kinetic visual violence, wanted to do Crash even before Cronenberg mentioned it, and, in Nick Roeg’s Bad Timing, made one of the great films about the eruptions of unconscious life.

Bad Timing (1980)

When you spent time with Jeremy, your sense of the clarity or consistency of his vision increases. He’s the gentlest and most generous of travelling companions — and a great DJ — yet, you do feel as if you’re in a mosh pit, or the green room of a 1972 Grateful Dead gi, or in New Mexico with Dennis Hopper having ingested a hallucinogen. You soon realise that this difference between urbanity and wildness — maybe between superego and id — isn’t a contradiction. It’s human nature, a way of stopping what’s in the secret box destroy your own or other people’s lives. It’s just that, in Jeremy’s case, the distance is very noticeable. His films are free from inhibitors. His characters get lots of psychic shocks much like jump-leads give shocks. A reference that Jeremy, a car-worshipper, might like!

- Mark Cousins

The storms of jeremy thomas is out now