If an artist creates something that no one engages with, did they even create? Looking at The Last Showgirl, Inside Llewyn Davis and more, Meg Walters explores the characters fighting for recognition.

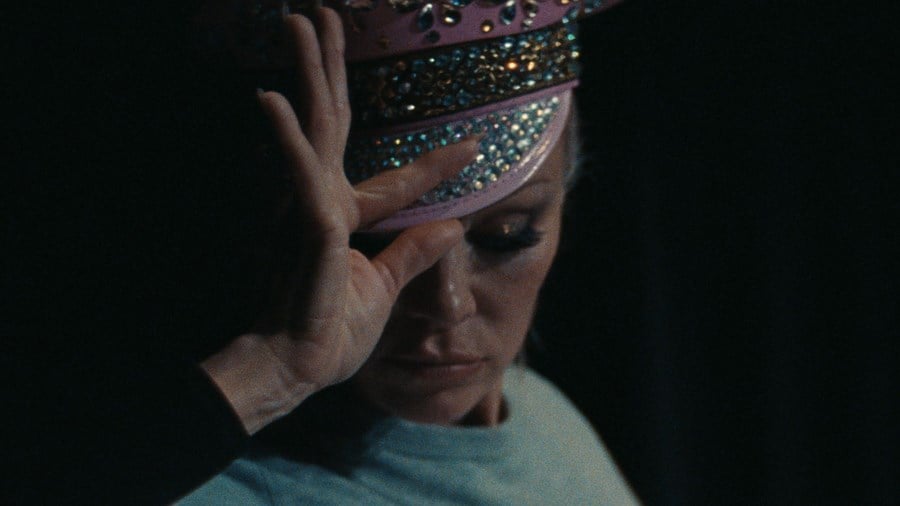

There was a moment in Gia Coppola’s The Last Showgirl when I suddenly, unexpectedly, started to cry. The scene in question featured Jamie Lee Curtis doing a bizarre interpretive dance to ‘Total Eclipse of the Heart’ (1983). It’s a pivotal sequence in the film that likely helped secure her Best Supporting Actress BAFTA nod.

Curtis plays Annette, an ex-showgirl now working as a casino waitress. Coppola lingers on Annette’s dance for just a little longer than is comfortable. In a single take, we see Curtis mount a platform in a brightly lit casino hall and begin to move in erratic, but deeply felt motions to the utter disinterest of the many gamblers around her. At first, she is merely an object of ridicule; Annette isn’t exactly your typical cocktail waitress, after all. Her skin is tanned to a dark leathery brown and bears the visible signs of ageing – lines, curves, stretch marks.

But as I continued to watch her dance so passionately to an audience of precisely no one, it hit me: this is a woman proudly doing what she loves despite the entire world telling her that she shouldn’t. It’s an oddly touching moment that captures the haunting beauty of the forgotten artist, who perseveres with their creative passion despite no hope of success or even appreciation. It serves as a small nod to the film’s bigger ideas.

Curtis has a powerful cameo in The Last Showgirl, but the film really belongs to a riveting, heartfelt Pamela Anderson. While Annette has made peace with the fact her showgirl days are over, Anderson’s Shelly is still clinging onto her career as a dancer in a Las Vegas revue. Once glitzy and glamorous, the show has since faded into a grimy, somewhat sad shadow of its former self.

The Last Showgirl (2024)

Shelly’s life as a showgirl is cut short against her will. In the opening scenes of the film, she and her fellow dancers learn that their show is closing down after three decades as a result of its vanishing, uninterested audiences. Still, Shelly clings on, practising her moves in her small bungalow and keeping the faith that a new job will emerge, despite countless signs that it’s time for her to hang up her feathers for good.

The Last Showgirl shares common themes with 1994’s Ed Wood, in which Johnny Depp plays a famous director who carries on making experimental films in the face of the derision and confusion of the wider industry. Similarly, in the Coen brothers’ 2013 Inside Llewyn Davis, we witness a week in the life of a fictional striving artist (Oscaar Isaac) working to break out in the folk scene in Sixties Greenwich Village. And then there’s 2023’s Showing Up, Kelly Reichardt’s look at the grim day-to-day struggles of an artist who just isn’t quite ‘making it’. Michelle Williams plays ceramicist Lizzie, who tries to find time for her upcoming art show in the midst of the slog of life, battling against her frustratingly unhelpful landlord, nursing strained family relationships and doing her full-time job at the local art college.

Showing Up (2023)

In line with all these characters, Shelly is a struggling artist. Like Ed, she is widely sneered at. Like Llewyn, Shelly pushes and pushes for some sort of recognition; they are both overlooked in favour of other performers and confronted by frustrated loved ones who can’t wrap their heads around this seemingly nonsensical commitment to a thankless career. And like Lizzie, Shelly always wants to be creating, but the world doesn’t always grant her the opportunity. To be an artist, each of these films remind us, is ultimately to be at the mercy of those who consume our art. If they don’t want it, we don’t always get to make it.

The Last Showgirl (2024)

In contrast to the previous portrayals of the realities of being a jobbing artist, The Last Showgirl presents us with an artist who has struggled for her entire career. When we meet her, she is not at the beginning, but the end. Shelly has already sacrificed so much to pursue her dreams, prioritising them over her daughter (a distrustful Billie Lourd), whom she gave away as a child to be raised by another family. She doesn’t want to lose her creative outlet. It’s sobering that, when Shelly tries to land a new dancing job, she is told – after a painfully embarrassing audition – that she is too old. Perhaps even more insulting? The producer says her dance style is a relic from a forgotten time. Similar to Annette’s heartbreaking performance, Shelly’s entire career has, in a way, become a passionate performance that no one wants to see.

The Last Showgirl (2024)

Unlike the characters in Ed Wood, Inside Llewyn Davis and Showing Up, Shelly toils away at an art form that never commanded much respect in the first place. It’s one thing to be an unappreciated director or folk singer or ceramicist; it’s quite another to be an unappreciated showgirl. Perhaps the lack of respect for the dance of the showgirl is what makes Coppola’s film so moving. It captures just how unforgiving true artistic passion can be, finding heart-wrenching beauty in an artist’s perseverance – even when their life’s work may well be invisible.

WATCH THE LAST SHOWGIRL IN CINEMAS