With its precarious workforce, culinary accidents and rigid hierarchy, La Cocina is just one of many films that delves into the pressure-cooker environment of a commercial kitchen. Here, Emily Maskell explores the trend.

They say the kitchen is the heart of the home; the commercial kitchen, on the other hand, has more negative connotations. In cinema, restaurant kitchens are ripe for drama and naturally heighten intensity. Temperatures rise, tempers flare and ambitions clash – while chefs scramble to get the perfect dish to the pass. Mexican writer-director Alonso Ruizpalacios knows this all too well, and embraces the chaotic nature of one such stainless-steel workplace in his nerve-shredding drama La Cocina. Like Boiling Point (2021) and Ratatouille (2007) before it, the film uses a stressful kitchen workplace to comment on wider labour, and interpersonal, issues.

La Cocina is based on Arnold Wesker’s 1957 play The Kitchen – which revolves around a frantic lunch rush – but makes a few notable changes. Ruizpalacios relocates the action from London to a Times Square tourist hot spot named The Grill. He also translates the title, and much of the dialogue, into Spanish, and swaps Wesker’s continental European immigrants for Latin American and Arab chefs. These updates allow the filmmaker to draw attention to the failures of the American Dream, establishing a racial and linguistic hierarchy (with white locals at the top and immigrants of colour at the bottom) that reflects the United States itself.

The first time Ruizpalacios’ camera marches through The Grill’s kitchen, it’s in pursuit of new employee Estela (Anna Diaz), a young Mexican immigrant with Michelin-restaurant experience. She’s rapidly introduced to the line cooks and eventually passed off to the workstation of chef, and fellow Mexican, Pedro (Raúl Briones Carmona).

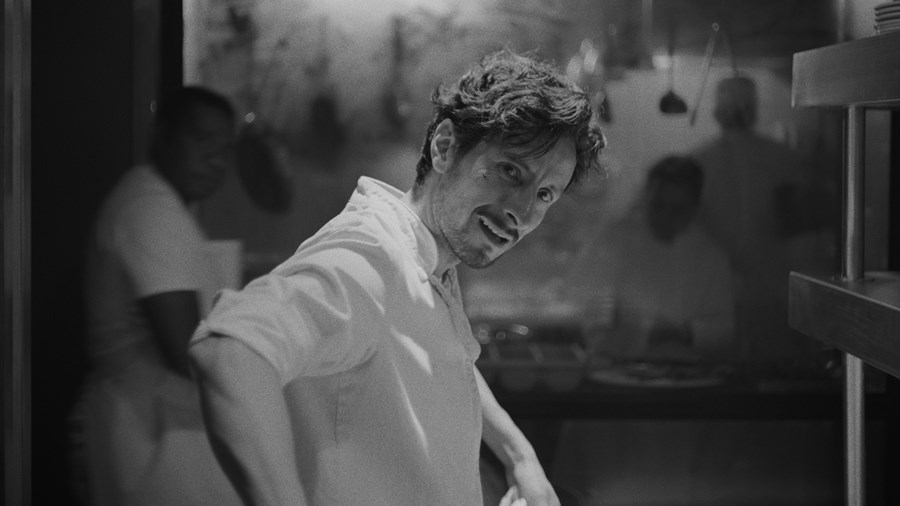

La Cocina (2024)

Like the viewer, Estela has little time to adjust before being thrown into service. Immediately apparent is the fraught pecking order that divides the chefs and waiters, exemplified by the relationship between Pedro and his pregnant girlfriend Julia (Rooney Mara). The former is restricted to the sweltering kitchen, whereas the latter is a white waitress who can ascend to the restaurant floor. Meanwhile, in the kitchen, there’s a divide between the English and Spanish speakers. Pedro, for his part, repeatedly receives harsh warnings for minor infractions; his white American co-workers, however, never face the same criticism.

The stark division of cooks and waiters is a point of contention that builds resentment. This kitchen’s disparity serves as a microcosm of broader labour exploitation. Many of The Grill’s employees are undocumented, meaning that the hollow promise of a US visa keeps them toiling in a system that takes advantage of them. To avoid deportation, these chefs put up with abusive treatment – like the hot-tempered steak-section chef Max (Spenser Granese), a white American, yelling at his hispanophone colleagues to ‘Speak English!’ – as they have no Plan B. This interracial tension boils over when Max insults Pedro’s culture and insinuates he’s only dating Julia for a potential visa; the two chefs end up wielding knives in a violent screaming match. The kitchen’s intensity is prevalent in these taut character dynamics, but the film’s frenzied camerawork also spotlights rising tension.

La Cocina (2024)

After an hour of mounting chaos, La Cocina arrives at an exceptional 13-minute one-take, where Ruizpalacios unravels the mayhem. The simple purpose of the kitchen, to deliver timely and appetising orders, results in breakneck action that leaves viewers breathless. The camera tracks the lifecycle of a meal as it’s prepared, plated, served and returned, while cinematographer Juan Pablo Ramírez’s boxy, monochrome frames become increasingly claustrophobic.

These black-and-white images visualise the stark opposition growing in the kitchen; there are no grey areas for these characters to drift in, they must take a side or be isolated. The compact, cluttered kitchen also gives kitchen staff little space to breathe, but is designed for chefs to circulate, allowing the camera to follow easily. Despite the progressively more disastrous events (knives draw blood, waitresses spill food and a broken drinks machine floods the kitchen), Ruizpalacios’ film and the perpetually moving 20-strong ensemble don’t slow.

Boiling Point (2021)

Boiling Point employs the same tension-building technique on an even larger scale, since its entire 92-minute runtime is captured in a single extended shot. The thriller sees head chef Andy (Stephen Graham), running on alcohol and drugs, losing control of his London kitchen on the busiest night of the year. La Cocina and Boiling Point’s operatic one-takes reach a fever pitch as their lead male characters heartbreakingly crumble. When Andy collapses and Pedro breaks down, the kitchens come to a screeching halt. Both directors highlight how disconcerting it is when the frantic kitchen plunges into still silence. Neither pause is a moment of respite, rather an anxiety-inducing scene where everything these chefs have worked hard for hangs in the balance.

Boiling Point (2021)

Despite its overwhelming pressures, the restaurant kitchen oddly serves as a backdrop for romance. Though cooking is a loving act of service, Pedro and Julia’s interactions in La Cocina are fleeting and confrontational. The kitchen environment seems inappropriate for their relationship, they share heady scenes in the walk-in fridge and have conversations about raising a child through the gap between the pass. But every stolen romantic moment is hurried, and their relationship grievances are gossiped about by colleagues. Similarly, in Pixar’s Ratatouille, the kitchen setting applies pressure to the budding romance between Colette (Janeane Garofalo) and new chef Linguini (Lou Romano), where the dinner rush, the reputational maintenance and, of course, the rat under Linguini’s chef hat threaten to spoil the partnership.

La Cocina (2024)

Instability dominates in the kitchen, everything can change during the course of dinner service. Linguini is continually on the verge of being fired in Ratatouille, and it’s three strikes and you’re out in La Cocina. In Ruizpalacios’ film, colleagues confide their dreams on cigarette breaks, before berating each other over the orders back in the kitchen. Even established relationships are liable to shift. When Pedro ecstatically tells Julia he is getting help with his immigration papers, she shares his jubilation. However, Mara masterfully transitions from a giddy smile to a forlorn expression as she heads up to the dining hall with a birthday dessert. Pedro’s news – and indeed the customer’s birthday – should be a moment of celebration, but Julia’s frown dampens any hope and suggests this isn’t the first time he’s been offered such a solution.

Ratatouille (2007)

Time and time again, filmmakers return to the restaurant kitchen, where people from all walks of life – with all sorts of struggles – gather to feed hungry mouths. The kitchen, and its rigid hierarchies, represent broader social structures, where the hard work of immigrants and the working class is exploited for corporate gain. Just like the lobsters dropped into scalding water in The Grill’s kitchen, La Cocina’s chefs are trying to survive at boiling point. Regardless of their language, position or immigration status, they put up a fight until the very last plate is served.

WATCH LA COCINA IN CINEMAS