For International Women’s Day, we’re revitalising our Women in the Spotlight strand where we celebrate the careers of female filmmakers. First up, Leila Latif’s essay on Jane Campion’s multifaceted, genre-defying oeuvre, which, among other things, presents sexuality with a distinctly female gaze.

Popular wisdom is that, when it comes to the films in awards contention, they are either unexpected wonders pushing filmmaking boundaries like Moonlight (2016) or Parasite (2019), or constitute lifetime-achievement awards for their creators in the vein of Martin Scorsese’s The Departed (2006) or the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007). Perhaps one of the more remarkable things about Jane Campion’s Oscar frontrunner The Power of the Dog (2021) is that it has equal weight in both categories. Adapted from Thomas Savage’s 1967 novel, it tells the story of ranch owner Phil Burbank, played by a never better Benedict Cumberbatch cast against type as a fiery hyper-masculine cowboy, and his brother George (Jesse Plemons), whose fraternal relationship is strained by conflicting ambitions. When George marries Rose (Kirsten Dunst), a widow with a teenage son, Phil loses control of his carefully constructed identity.

The Power of the Dog (2021)

The Power of the Dog is a ravishing and quietly subversive film. It is Campion’s eighth feature and her first since 2009’s Bright Star, an understated 19th-century romance about John Keats and Fanny Brawne. For The Power of the Dog, even though the novel and the film are set in Montana, Campion returned to her native New Zealand to shoot for the first time since 1993’s modern classic The Piano, which saw Holly Hunter play a mute Scottish pianist sold into marriage with Sam Neils’ frontiersman from the country’s North Island. Unlike in The Piano, the New Zealand location wouldn’t be obvious to anyone watching The Power of the Dog, the use of natural light on open horizons combined with seamless special effects, and period detailing in spoons, collars and saddles made this 1920s Montana entirely authentic. It’s a feat that Campion accomplishes in so many of her period dramas. In Bright Star, The Portrait of a Lady (1996), The Piano and The Power of the Dog, the place in time feels lived-in and textured, from the weight of Isabel Archer’s petticoats to the smell of cowboy Phil Burbank’s unwashed leather chaps.

The Piano (1993)

Even when tracking a single character over 40 years, as Campion does in An Angel at My Table (1990) – an adaptation of novelist Janet Frame’s autobiography – each element of Frame’s coming-of-age is realised not just in the three actors’ performances, who play her at different life stages, but in the subtly shifting, slowly modernising world that Campion creates. The director keeps the camera and the narrative focused on the details – the tightness of the leather on Janet’s school shoes, the agony of electric shock therapy – while still evoking her subject’s blossoming womanhood and creative genius. The strange alchemy of An Angel at My Table is how Campion occupies both ends of the spectrum, shifting between empathy and dispassion towards her characters. As in The Power of the Dog, here the worst of actions have complex motivations, while their consequences are relayed with a detached matter-of-factness.

An Angel at My Table (1990)

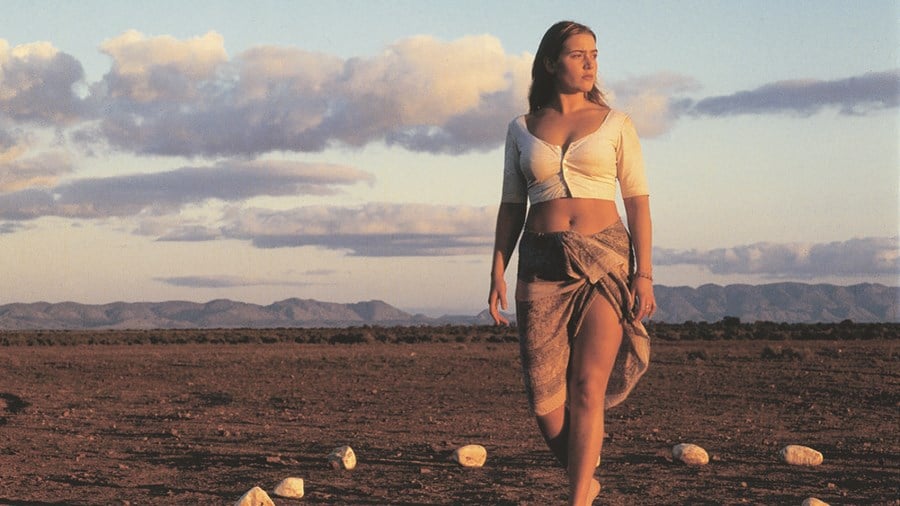

Boiling a director with Campion’s range down to a few signatures like creating a profound sense of isolation and casting actors against type is reductive, but her strongest trait may well be her almost peerless knack for sensuality and sexual desire. The Power of the Dog doesn’t have the explicit sex of The Piano or In the Cut (2003), and yet it portrays desire through the mounting of a saddle, the gripping of a rope, eyes meeting followed by the clenching of a jaw. Campion is no less artful when she sweeps aside the subtext and fills the screen with writhing bodies and gentle moans. Kate Winslet, fresh off her success in Titanic (1997), made Holy Smoke with Campion in 1999, about Ruth, a young Australian woman embroiled in a religious sect. Her family hire ‘exit counsellor’ PJ (Harvey Keitel, teaming back up with Campion after playing a seductive forester in The Piano) to deprogramme her, but the dynamic between the two becomes complicated by an intense sexual chemistry and shared obsession. When they do give in to their desires, Campion draws out the scene so slowly – honing in on intense gazes, Winslet undressing and the first tentative touches before they consummate their relationship – that the boundaries of where sex begins and ends feel immaterial. While the relationship between PJ and Ruth filled with unbridled sexual desire that desire would be even darker in her next film In the Cut, where Campion switched from psychosexual drama to full-blown erotic thriller.

Holy Smoke (1999)

In the Cut was the most poorly received of Campion’s works despite being an absolute masterpiece, much of the attention around it upon release was dispiritingly puerile, centring on Meg Ryan’s nudity. By the time Campion made In the Cut, it was long after the heyday of the erotic thriller, so for a director then best known for being the first woman to win the Palme d’Or for The Piano, it seemed an unusual choice. But just as with her previous films, In the Cut has a complicated female protagonist at its centre (Ryan’s mild-mannered English teacher), who is torn between what is expected of her and what she truly desires. Where the plot points may feel familiar (a serial killer on the loose, a woman attracted to a potentially dangerous man, a third-act twist…), Campion offers a vital subversion of the male perspective, reframing something familiar through a distinct gaze of feminine lust.

In the Cut (2003)

What might be most impressive about Campion’s oeuvre is how distinct her gaze has always been. Her first feature Sweetie (1989), where Kay (Karen Colston), an insecure woman paralysed by dependence on superstition and her obnoxious sister Dawn (Geneviève Lemon), offers a striking and disturbing look at sororal bonds. Its two sisters, who are societally expected to treat each other with unwavering kindness, are instead agonisingly destructive towards one another. More challenging still is that Campion doesn’t allow the siblings redemption in Sweetie, and similarly frustrates the viewer’s desire for reconciliation with the toxic relationship between brothers Phil and George in The Power of the Dog. In both films, the director concludes that symbiosis is impossible and that, in order for one sibling to thrive, the other must wither.

The Power of the Dog (2021)

The seeds of what make The Power of the Dog a masterwork – i.e. dismantling prototypical Western mythology – are present in every film Campion has made, in that they all deconstruct genre norms to create sensual works populated with complicated characters. Campion’s films aren’t interested in retelling myths or employing familiar tropes, their beauty lies in their complexity. Audiences can perceive The Power of the Dog as a culmination of decades of excellence or a single piece of subversive art that defies expectations. Either way, Campion’s films should remind us to consider that all things contain multitudes, as her varied career has certainly proved.

WATCH THE POWER OF THE DOG IN CINEMAS