Jake Abatan considers how Kate McCullough’s cinematography allows the audience to perceive the world through the eyes of a shy young girl called Cáit in Colm Bairéad’s incredible debut film The Quiet Girl.

There’s a quiet confidence to director Colm Bairéad’s debut feature, which follows a timid young girl called Cáit who slowly comes out of her shell over a summer spent with relatives. Appropriately titled The Quiet Girl, this slow and considered adaptation of Claire Keegan’s short story ‘Foster’ allows its cinematography to do the talking.

The Quiet Girl (2022)

The source material demanded such an approach for the screen adaptation, as Cáit’s thoughts and feelings are communicated through the visual language. According to the film’s director of photography, Kate McCullough (who won the IFTA Award for Best Cinematography this year for The Quiet Girl), this is a film ‘about the unsaid, the emotionally unspeakable’, which means that ‘the image has to work a little harder to deliver these subtleties on screen’. The foundations were laid by the decision to shoot in Academy ratio. With less space available in the frame, it encouraged more assertive compositions from McCullough. ‘I found in the process that I had to commit to the framing,’ she says, ‘I enjoyed that when finding a language for this film.’ The result is a visual language that is elegant and precise, the boxy frame evoking themes of oppression, but also intimacy.

As Cáit walks home alone or runs away from school bullies, a static camera keeps her tethered within the frame, but her quiet curiosity is ever-present. McCullough proposes that we can think of the aspect ratio as being ‘suggestive of Cáit’s naivety, a world lying outside the frame yet to be explored or even understood.’ Labelled ‘The Wanderer’ by her father, she clearly desires to escape her current reality, but often finds herself a passenger in it – the world moving past her as she watches from the backseat of her father’s car.

The Quiet Girl (2022)

‘The cinematography had to surrender itself to Cáit’s frame of mind throughout,’ McCullough shares, ‘Once we have established that it is her story to tell you can, as a filmmaker, technically step outside the POV [point of view] convention without breaking up the illusion.’ It is through the cinematography that we begin to understand the world of the film through Cáit’s observations. Her parents’ house isn’t just shown to be a cramped homestead, we are made to feel how stifling an environment it is for her. Shabby walls dominate the composition, giving the space a claustrophobic feel, and family members are often obscured by door frames and window sills signalling Cáit’s emotional separation from them. When peering through the bannister one night, she overhears her father say, ‘Tell them they can keep her as long as they like’, finally putting into words – however indirectly – what the composition has been telling us all along: there is little space for Cáit here.

The Quiet Girl (2022)

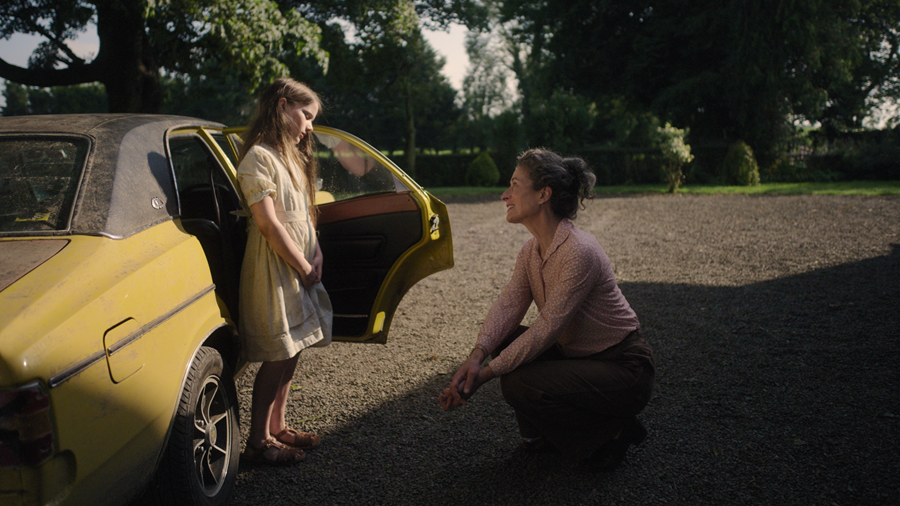

The ‘them’ her father is referring to are Seán (Andrew Bennett) and Eibhlín (Carrie Crowley) Kinsella, distant relatives of Cáit’s mother with whom she will spend the summer to help ease the burden at home. As her father drops her off at the Kinsella’s farm, we soon learn that this is a place of abundance – food, space, time and love are in vast supply. Whilst looking for the loo in the new house and exploring the empty rooms, Cáit is captured with a larger depth of field highlighting the capacious surroundings, but also how small they make her feel. Eibhlín is quick to put her worries at ease. Her gaze falls instantly upon Cáit’s muddy ankles as they meet for the first time, and we can almost feel her maternal instincts kick in. Before long, those same ankles are submerged in a warm bath as Eibhlín washes Cáit, giving her the kind of attention and care her burdened mother does not have the luxury to.

The Quiet Girl (2022)

It is here, under the Kinsella’s guardianship, that Cáit’s confidence and curiosity begin to flourish. Though the framing remains somewhat restricted by the aspect ratio, McCullough states that ‘the only time Cáit challenges these boundaries on either side is when she’s running, she’s sort of falling in and out of the frame and this gives a sense of freedom and strength to her in these moments.’ We rarely share Cáit’s literal point of view, but moments like these allow us to experience what she is feeling.

In contrast to the untamed hay that surrounds Cáit’s house, the Kinsella’s farm is a veritable Garden of Eden, overflowing with Rhubarb and Gooseberries – the sounds of farm animals abound. Nature here comes to symbolise Cáit blossoming into her true self. There is a moment early on in her stay on the farm when Cáit accompanies Eibhlín down to their well to get water. Time slows as Cáit takes in this new experience; McCullough’s shot compositions, together with the gentle ebb and flow of the camera movements, create a feeling of quiet grace – a peacefulness that permeates the screen. A close-up lingers on her ladle as she drinks from the well, an elixir of contentment. ‘The opening shots are a portrait of aloneness and respite in nature, where Cáit is framed from a distance,’ McCullough points out, ‘Later, exterior frames at the Kinsella’s are suggestive of a coexistence with nature as she adapts to a new way of living, a new way of seeing and being seen.’

The Quiet Girl (2022)

It takes time for Cáit to adapt to her new surroundings, and despite Eibhlín’s assurance that ‘There are no secrets in this house,’ we get the distinct sense that there is a lot left unspoken. Perhaps this is due to the particular way their silhouettes fall on the train-themed wallpaper in the bedroom Cáit is staying in, or how, after her father drives off with her suitcase left in the backseat, she’s given the clothing of a young boy to wear. At first, Séan wishes Cáit goodnight without so much as a glance over his shoulder. It’s clear from his reluctance to look her in the eye that he’s guarding himself. As he sweeps the milking room floor, a point of view shot from Cáit’s perspective holds the milking apparatus as an obstacle between them, but when she wanders off to find a broom to help him, Séan’s distress betrays his true emotions. The feeling that Cáit is filling a void continues to build until a tactless neighbour reveals to her why that is.

The Quiet Girl (2022)

Eibhlín, understandably upset by the neighbour’s careless blathering, chooses to be with herself and her own thoughts that evening to deal with the grief the event had triggered. Séan takes Cáit to the beach to process what the little girl has just learnt. Quietly and patiently he tries to explain, but when she does not respond he tells her, ‘You don’t have to say anything. Always remember that. Many’s the person missed the opportunity to say nothing, and lost much because of it.’ This profound strength of silence shines through in McCullough’s assured cinematography, a sentiment that Cáit, under the compassionate care of Séan and Eibhlín, begins to fully understand. For this family, the wounds opened by the truth are healed not with words but with quiet contemplation, and the sense of belonging for Cáit, the quiet girl, becomes clear. Even though she cannot stay with the Kinsellas, the bond they’ve formed is stronger than words could ever communicate.

The Quiet Girl is in cinemas and on Curzon home cinema from Friday 13 May