To celebrate 25 years of Notting Hill, Yasmin Omar looks back at how its star has delivered heart-soaring amorous speeches over the years, with all the attendant fumbling and eyelash-fluttering.

Hugh Grant Romantic Heroes come in two distinct moulds. There are the slimy, silver-tongued, would-sleep-with-your-best-friend cads like Bridget Jones’ Daniel, who love you and leave you after a bout of saucy instant-messaging and a sex-filled minibreak weekend. Then there are the bewildered, tongue-tied, floppy-haired fops in the vein of Four Weddings and a Funeral’s Charles, a soft-hearted monogamist on the lookout for ‘thunderbolt’ chemistry in a future wife, but hampered by his cringing social ineptitude. Grant’s performance as the bumbling, crinkly-eyed Charles launched him to international stardom, and introduced us to his withering humour. May the record show that in 1995 he was accepting a Golden Globe ‘with tremendous ill grace [and] grudgingly recognising the contribution of other people’ in his soon-to-be signature deadpan.

Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994)

Off-camera, Grant is fully at ease whenever he gives a speech; on it, his various fops radiate discomfort. In an early Four Weddings (1994) scene, we are shown Charles’ ineloquence when he utters a faux pas so mortifying he bangs his head self-punishingly against a marquee pole, as if trying to knock the memory of the encounter out of his brain. His later amorous declaration to Carrie (Andie MacDowell) – the alluring and, at this point, engaged American he’s smitten with – doubles down on that awkwardness. Charles has seemingly decided that he’s not going to confess his feelings to Carrie, but has a last-minute change of heart and, with a ‘Fuck it!’, sprints down the South Bank after her. Upon catching up with Carrie, he is out of breath and visibly tense.

Grant’s anguished performance is excruciatingly authentic, he’s like a fidgety kitten uselessly clawing to be released from its carrier. He replicates that nervous habit of not knowing what to do with your hands: pointing and clasping them together and balling them into fists. He barely looks at MacDowell, keeping his eyes closed for significant stretches of his speech and, even when they are open, repeatedly flicking his gaze down and away from her. Then there’s the blinking, that Hugh Grant blinking. This is an actor who flutters his eyelashes. A lot. Here, it communicates Charles’ emotional unsteadiness. There is no way he needs to lubricate his eyeballs that many times in under a minute, therefore the incessant blinking clues us in on the character’s mounting anxiety. It’s all very endearing, watching a quivering, anxious man in short-shorts – an uptight Englishman, no less! – bare his soul on the streets of London.

Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994)

This Four Weddings sequence works perfectly well without sound, since Grant’s pained expressions do much of its heavy lifting. However, Richard Curtis’ dialogue adds a whole new dimension to it. Charles apologises to Carrie before he’s said anything, which undercuts the forthcoming speech and prematurely anticipates her rejection. He really, really struggles to articulate his feelings, every other word is ‘um’ or ‘ah’, and the monologue is delivered in a stumbling fashion, with Charles tripping spectacularly over his own words.

The contrite tone continues as Charles self-admonishes and stops short of admitting his affection: ‘This is a really stupid question’; ‘I just wondered if there’s any chance… I mean obviously not’; ‘No, no, no, of course not’. Eventually, he spits out, ‘In short, to recap in a slightly clearer version – in the words of David Cassidy in fact, while he was still with the Partridge Family – “I think I love you”.’ It’s an ‘I love you’ tempered by a muddying ‘I think’, further diminished by being a pop-song quote. Charles won’t say it again, despite Carrie’s insistence, seemingly in an act of self-preservation. He knows she doesn’t care for him that way, and is seeking to cushion his fragile heart.

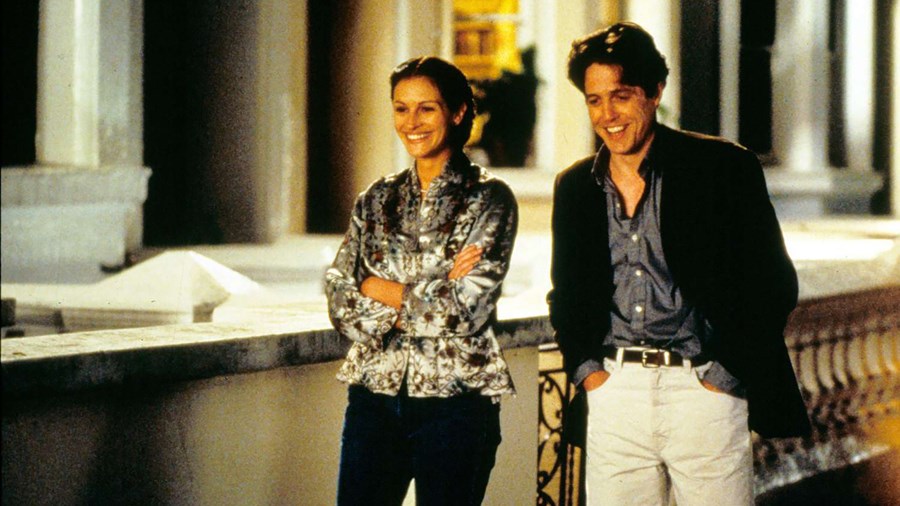

Notting Hill (1999)

Like Charles’, William’s heart in Notting Hill (1999) is ‘relatively inexperienced’, and also belongs to a rather glamorous, inconsistent American (in this instance, Julia Roberts’ A-list actress Anna Scott). The dweeby proprietor of a quaint, blue-doored travel bookshop, William is Grant’s Greatest Fop Character. If you’re about to challenge me, I’d like to remind you that he unironically – and repeatedly – cries out ‘Whoopsie daisy!’ when scaling a fence, and, in a pinch, wears his prescription scuba-diving goggles to the cinema.

The Notting Hill love speech that everyone remembers is, of course, Roberts’ canonical ‘I’m just a girl, standing in front of a boy’. Grant’s response, in the film’s penultimate scene, is a make-up declaration, for William initially rejects Anna’s ‘kind offer’ of a relationship then thinks better of it and scrambles to win her back, hightailing it to a press conference to intercept her before she flies across the pond. Circumstances dictate that the forum for his heart-spilling be a ballroom surrounded by dozens of journalists. It is public, alarmingly so for William, who has difficulty expressing himself one-on-one to fruitarians and film stars alike.

Notting Hill (1999)

A direct line can be drawn from the Four Weddings speech to the Notting Hill one. When picked upon to ask a question – and reveal his true feelings – William begins in much the same way Charles would. Lowering his raised hand, and furiously blinking, he haltingly addresses Anna, ‘Yes… Miss Scott.’ So far, so Grant. And yet, there is a crucial difference: confidence. His eyes meet (and hold!) Roberts’. His voice is clear, controlled and resonant. His pauses, though still apparent, are less panicked, more considered; he’s weighing words rather than scrabbling to find them.

The Notting Hill stakes are arguably lower than Four Weddings’, since Anna has already laid her cards on the table. However there is still the very real possibility that she rejects (and humiliates) William not only in front of everyone present, but also everyone who reads the inevitable reporting on this press event. Grant’s expression says as much. There’s a desperation to his pleading, woebegone eyes as he waits for her answer. When she takes him back, his body swells with relief, he stands up fully with his chest ballooning in delight. It’s a subtly affecting piece of acting, a satisfying completion of William’s character arc.

Notting Hill (1999)

With a few exceptions – the unctuous Daniel misguidedly trying to win over Bridget Jones by telling her ‘if I can’t make it with you, I can’t make it with anyone’ – Hugh Grant’s cads are willing to humble themselves in the name of love. The impact of the actor’s early-2000s rogues is heightened by our growing understanding of Grant’s off-screen persona. In other words, we got to know him as this loquacious, self-effacing wisecracker in interviews, so the disarming sincerity of his rom-com speeches – where he lets unguarded emotion surge forth – hits that much harder. Take George in Two Weeks Notice (2002). He’s a billionaire playboy who demolishes local landmarks for private gain and incessantly torments his assistant, Sandra Bullock’s Lucy. (Calling a bridesmaid out of a wedding to help you decide which suit to wear for the Miss New York contest is frankly inexcusable.)

Two Weeks Notice (2002)

George’s final-act romantic declaration, his last-ditch effort to win Lucy’s heart after having been so careless with it, is, to quote the woman herself, ‘actually quite perfect’. It’s a doubled speech, in that he reads Lucy an address he’s just delivered to another crowd, only this time in front of colleagues at her new office. But George and Lucy might as well be in the room alone, because he speaks to her with a searing intimacy potent enough to make everything else melt away. He looks up from the notecards he’s been reading to tell Lucy she’s ‘absolutely beautiful, and the only one of her kind’, and takes responsibility for the ‘cruel things’ he’s said that ‘drove her away’.

There’s a stillness to Grant here, as if he’s steeling himself for disappointment, while a tornado of contrition, hope and affection swirls behind his eyes. Like William in Notting Hill, Lucy initially turns down George, and the actor’s understanding, but mournful, resignation when he walks away with a ‘sorry to disturb’ – the exact same words spoken by a defeated Charles after his failed Four Weddings speech! – is crushing. You can see the effort he’s making to hold his shoulders high and project gracious acceptance. It’s a performance that makes you want to reach through the screen and give him a consoling hug.

Two Weeks Notice (2002)

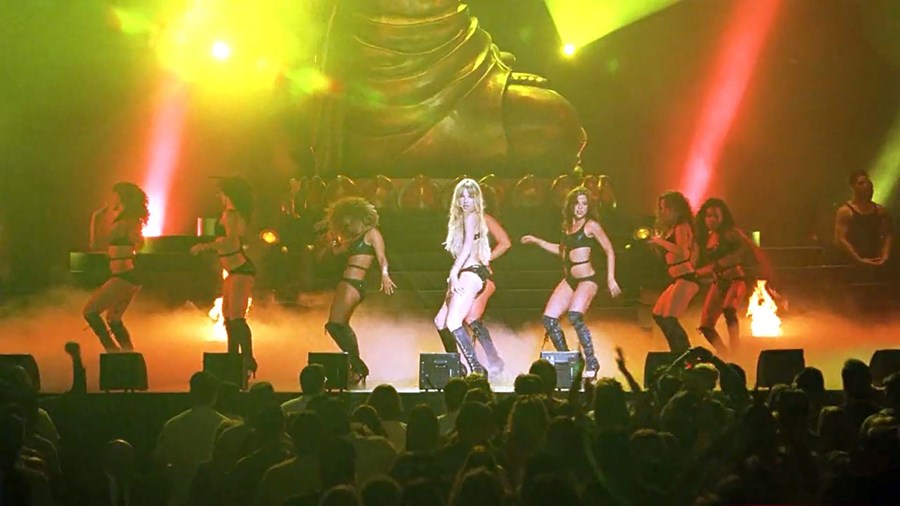

Similarly, Grant’s romantic declaration in Music & Lyrics (2007) is designed to win back his girlfriend and make amends for previous bad behaviour. An over-the-hill Eighties musician, Alex (Grant) has threatened his new relationship with kooky lyricist Sophie (Drew Barrymore) by confirming that he believes her worst fear about herself, that she’s not fulfilling her creative potential, to be true. In the grandest gesture of Grant’s rom-com career, he performs the original song ‘Don’t Write Me Off’ to Barrymore’s Sophie in front of a sold-out Madison Square Garden. The number is part of Haley Bennett’s pop star Cora’s highly produced show – complete with pyrotechnics, dry ice and a giant, rotating Buddah – and it runs counter to everything that came before in its no-frills simplicity.

Music & Lyrics (2007)

For ‘Don’t Write Me Off’, Alex is seated alone at a grand piano, and several wide shots emphasise his vulnerability on that massive stage by himself. (The still apparent Buddah is the ghost at the feast.) Even the arrangement of the song is stripped-back: it’s just Alex’s gentle voice and a handful of repeated chords. Grant looks dejected from the outset, preparing for failure before he’s taken a shot at victory. He keeps pulling away from the microphone for the first few bars, trepidatious, and he utters the line ‘Now I need you’ with a plaintive sincerity that’s more like talking than singing. The lyrics themselves, noteworthy because Alex composes melodies not words, are apologetic (‘So please forgive these few brief awkward lines’), self-aware (‘Based on my track record, I might not seem like the safest bet’) and repentant (‘I’ve already blown more chances than anyone should ever get’). He finishes the song and puffs out his cheeks, both exhausted and uneasy. With this small gesture, Grant communicates Alex’s state of mind – after years of coasting (in life and love), he’s putting himself out there and it’s uncomfortably revealing.

Music & Lyrics (2007)

Whether delivered by jittery fops or hurtful cads, Hugh Grant’s romantic speeches are united by one thing: vulnerability. It doesn’t matter if they’re sung before a 19,500-strong stadium or sputtered out on the South Bank, all of them showcase the anxiety-inducing risk of putting your heart on your sleeve in the – sometimes futile – hope that your beloved will follow suit. The eyelash fluttering may persist from role to role, but Grant ably presents the variety of his characters’ churning emotions, from total mania (Four Weddings and a Funeral) to quiet confidence (Notting Hill) and repressed disappointment (Two Weeks Notice). He is, quite simply, the Romantic Hero of our time.