The graphic novelist talks to Michael Leader about creating the film’s limited-edition poster, watching audiences react to his work in real time and the subtle art of adaptation.

A passionate modern romance that intertwines stories of sex, existential crises and millennial angst, featuring sleek black-and-white cinematography, and starring a cast of hot young hopefuls. You'd be forgiven if you looked at director Jacques Audiard's Paris, 13th District and thought, well, what could be more French than that?

The twist is, the film is technically a comic-book movie: a radical adaptation of the work of American cartoonist Adrian Tomine, whose bittersweet character-driven stories have been published under his Optic Nerve banner for over 30 years. Collected in book-length graphic novels such as Summer Blonde and Killing and Dying (upon which Paris is loosely based), Tomine’s stories are drawn with a sharp line, and written with an even sharper insight into the mundane complexities of everyday life.

Paris, 13th District (2021)

It was Audiard who made the first, very direct, move to adapt the artist’s work. ‘About six years ago,’ Tomine remembers, talking over Zoom from his home in Brooklyn, ‘I got an email out of the blue, while I was on vacation with my family. It was asking if I'd have any interest in having my work adapted to film, and the sender was just “J. Audiard.”’ After a moment’s reflection, Tomine, who had previously turned down requests to option his work for the screen, fired back a reply: he was interested. ‘And then I had a moment of panic where I was like, “What if this is… Jimmy Audiard?”’

Thankfully, it was Jacques, fresh off a Palme d’Or win for Dheepan (2015), and soon to be shooting his first English-language film, the unconventional western The Sisters Brothers (2018), adapted from the novel by Canadian writer Patrick DeWitt. Unlike that latter film, the Tomine project was a much less straightforward adaptation. Audiard had optioned a series of unconnected short stories from the pages of Optic Nerve: ‘Hawaiian Getaway’, following a former call-centre worker cast adrift in an uncertain period of her twenties; ‘Amber Sweet’, about a young woman whose social life is plagued by her uncanny resemblance to a porn star; and ‘Killing and Dying’, in which a teenager pursues stand-up comedy as a way of persevering through trying times at home. (A fourth Optic Nerve story, ‘Summer Blonde’, was also optioned, but didn’t make it to the big screen.)

Paris, 13th District (2021)

In collaboration with co-writers Céline Sciamma and Léa Mysius, Audiard would cherry-pick details, situations and characters from these stories and weave them together, with the protagonists crossing paths in the high-rise-populated Parisian neighbourhood that gives the film its French title, Les Olympiades. However, this plan wasn’t immediately clear, at least not to Tomine. ‘It was very mysterious to me how he intended for them all to coalesce,’ he recalls. The stories encompassed over a decade of Tomine’s creative and personal life, from 1999’s ‘Hawaiian Getaway’ to the relatively recent ‘Amber Sweet’ and ‘Killing and Dying’, both published in the 2010s. In between these stories, Tomine moved from his home state of California to New York City, he got married and became a father. ‘I think of those as two very distinct eras, [from] two pretty different artists. To combine them seemed surprising to me.’

While the film was in development, the author only received brief updates on the proceedings: irregular titbits from the producer, and one short meeting with Audiard in a hotel lobby while he was in town promoting The Sisters Brothers (‘It was a formality, a friendly gesture, just to say hi’). Then a script arrived. ‘That was the moment where I realised very, very definitively what the film was and how much this was a new work of art. It was using my stuff as a very basic premise, and really going off in its own direction. A lot of those translations were very appealing to me, because of my own appreciation of French cinema and the warm reception my work has always received in France. In a way, it all made sense to me. That was value added.’

Paris, 13th District (2021)

A lifelong lover of film, now living in a city that is a haven for cinephiles, Tomine ate up the small details he heard from afar as production proceeded during the pandemic: ‘Black and white, episodic, young people, quotidian life, a quick and loose shoot… I started to get the sense that maybe Audiard was reaching back to [the] French New Wave. As I was learning these bits of information, I was thinking about Éric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales, which I had loved as a young person discovering international cinema.’ These films – including My Night At Maud’s (1969), Claire's Knee (1970) and Love in the Afternoon (1972) – are finely observed, naturalistic dramas that, much like Tomine’s own work, offer incisive character studies laced with irony. Rohmer diehards will note, too, that the Six Moral Tales started life as short stories, before the director adapted them for the screen himself, something Tomine is now doing for his graphic novel Shortcomings and the graphic memoir The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist. The experience of being adapted has naturally had an impact on Tomine’s approach to writing the adaptation himself. ‘I think it has opened me up to the idea of departing from the source material, more than I would have before,’ he explains. ‘Now I’m adapting my own work, I’m viewing it with a mindset that the goal is to make a good film, not a perfect adaptation.’

Paris, 13th District (2021)

Flash forward to June 2021. A post on Tomine’s Instagram account shows the author, placed slightly off-centre in the frame, sitting alone in an empty screening room. The caption notes that this was his first visit to a cinema in 16 months, and it was for a private screening of the finished cut of Paris, 13th District. ‘I don’t know if I’m allowed to say much about it yet,’ Tomine wrote, ‘but… it’s absolutely beautiful. I loved it, and I think you will, too. What an honour, and what a strange, unimaginable experience.’ Naturally, the photo was rendered in black and white.

‘It was one of the strangest experiences of my career,’ Tomine recalls. ‘Almost everything else in my work up to that point had been self-generated and self-edited, so seeing something that I was involved in, but not really… something that was a massive collaboration amongst hundreds of people… something that started with a few comics of mine that I created in my bedroom. It was very moving to me.’ The title of that memoir, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, comes to mind again, now with a new dual meaning: alluding to both the solitary work of making comics and the unique experience of having that work remade on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Paris, 13th District (2021)

Eventually, though, Paris came to Tomine, when the film screened at New York’s Lincoln Center, followed by a Q&A session with Audiard, Tomine and the film’s breakout star Lucie Zhang. ‘You never get that experience,’ he explains. ‘I’ve never seen my work be ingested – I never watch a reader laugh or anything like that. But, then again, this wasn’t exactly my work…’

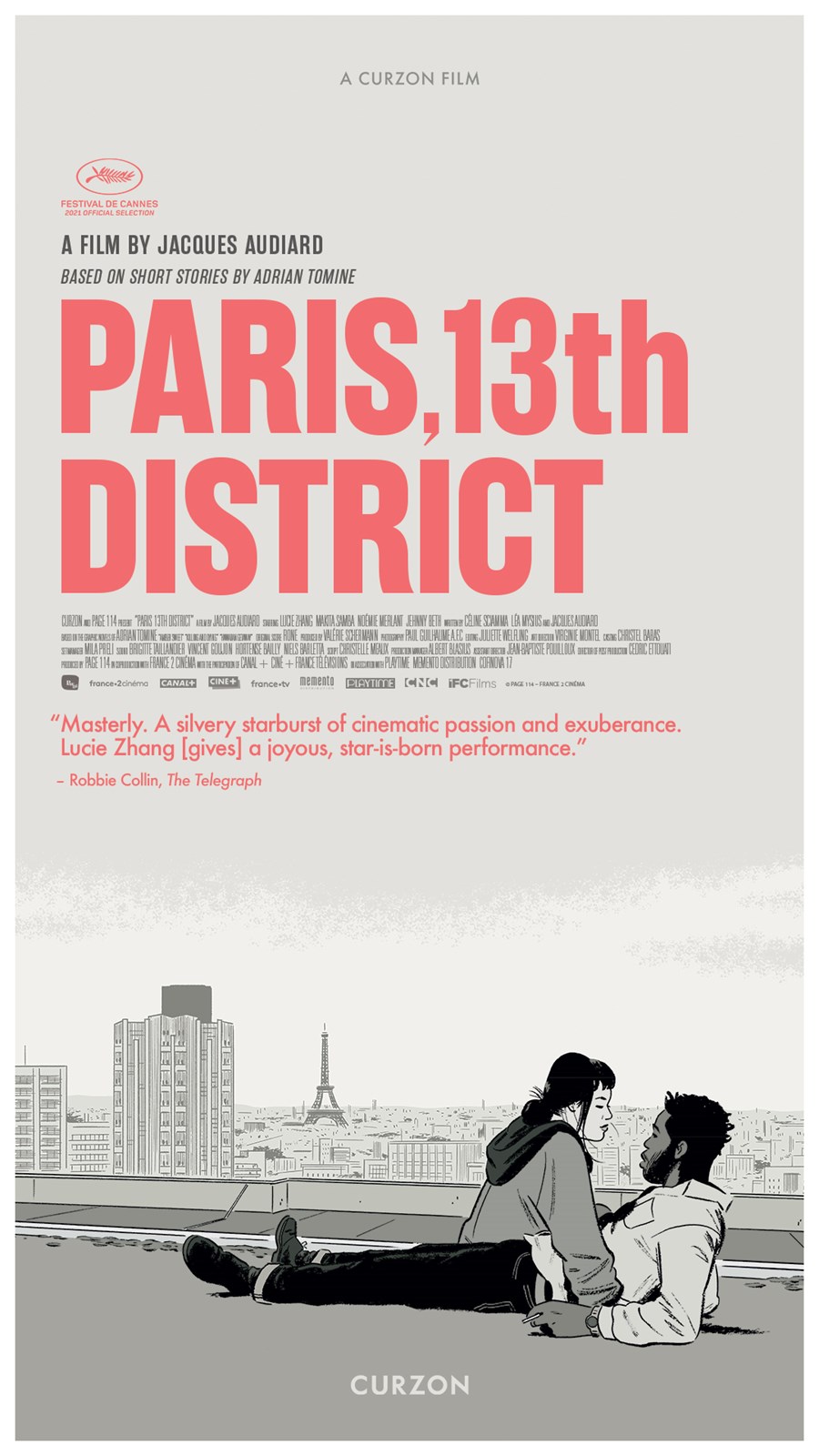

Another full-circle moment arose when Tomine was tasked with creating a piece of art that would serve as one of the film’s posters, effectively re-translating Audiard and company’s adaptation of his comics back into his own artistic language. Tomine’s illustration work, which has graced covers and interiors of magazines such as The New Yorker for over 20 years, is just as celebrated as his work in comics, chronicling contemporary life in the big city with a keen eye for everyday details that capture a distinct mood or miniature narrative in one frozen moment.

‘I approached the poster as I would any other commercial-illustration job,’ says Tomine, describing the familiar process of mocking up rough sketches for client approval. ‘It was only after finishing it that I realised I had drawn my rendition of actors playing characters based on characters I had drawn in my books. It's a meaningful image to me, one that encapsulates a very unusual and gratifying seven-year experience.’

Reflecting on the end of this long and uncommon process, Tomine elaborates further: ‘It’s rare in life that you have a full arc of a story. Life, generally, is kind of nebulous and endlessly ongoing. But I flash back to the time when I was agonising over whether or not to sign the contracts, and what a leap that was for me, because I had said no to these kinds of opportunities many times in the past. I had so many questions and so many uncertainties. And I thought, no matter what, this is an experience that I would like to have had at the end of my life. And I made the right choice.’

Like the most impactful and poignant Tomine art, the finished poster for Paris, 13th District finds our subjects suspended in time, sharing an intimate moment, both hemmed-in and embraced by their urban surroundings, albeit with one new addition: the unmistakable profile of the Eiffel Tower in the distance behind them. Now, what could be more French than that?

PARIS, 13TH DISTRICT IS NOW SHOWING IN CINEMAS AND EXCLUSIVELY ON CURZON HOME CINEMA