Filmmaker Pablo Berger founded a studio for his first foray into animation, a beautiful, dialogue-free drama about the power of friendship. Here, along with animation director Benoît Feroumont, he tells Michael Leader about their creative process.

Who can predict where inspiration will take you? Certainly not Pablo Berger, whose latest film, Robot Dreams, has led him into previously unexplored territory. ‘I am a lucky director,’ he admits, ‘because I have producers who encourage me to surprise them.’ One can only imagine their reaction, then, when the filmmaker – whose career thus far has encompassed bawdy comedies (Torremolinos 73, 2003), silent-film fairytales (Blancanieves, 2012) and madcap magic realism (Abracadabra, 2017) – presented them with yet another stylistic curveball: feature-length animation.

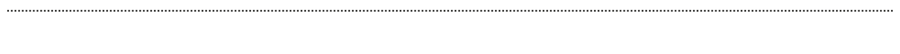

Berger, an avid collector of wordless comics and picture books, had previously read Sara Varon’s dialogue-free graphic novel Robot Dreams over a decade ago, but it was after wrapping up work on Abracadabra that he found himself scanning his bookshelves, and his eyes landed on it once more. Focusing on the anthropomorphic Dog and his mechanical pal Robot, the story wends its way through the seasons, telling a tale of loneliness, friendship and, ultimately, loss and nostalgia. ‘When I finished the book, I was in tears,’ Berger recalls. ‘But I realised that when I read it this time, I was visualising my own film.’ The catch was that Berger had never worked in animation before, and hadn’t even considered approaching the artform until that moment: ‘I wanted to tell this story, and there was no other way but to take this path, and make an animated film.’

Robot Dreams (2024)

The filmmaker’s first instinct was to seek out some expert help. Ireland’s Cartoon Saloon, the world-renowned studio behind vibrant, Oscar-nominated films such as Song of the Sea (2014) and The Breadwinner (2017), were initially on board – until the partnership was scuppered by the COVID-19 pandemic. That led Berger to move on to plan B: ‘So, we did it the way we weren’t supposed to. We created our own studio.’

A studio, though, is more than just furniture, computers and software: it needs people. Artists from across Europe descended on the production offices in Spain, including animation director Benoît Feroumont, a veteran comic-book artist and animator, who counts among his credits Belleville Rendez-vous (2003) and Cartoon Saloon’s debut feature The Secret of Kells (2009). Feroumont had also directed his own short films, such as Bzz (2000) and The Lion and the Monkey (2017) – two wordless works that, much like Robot Dreams, focus purely on the movement and expressions of the characters to convey meaning.

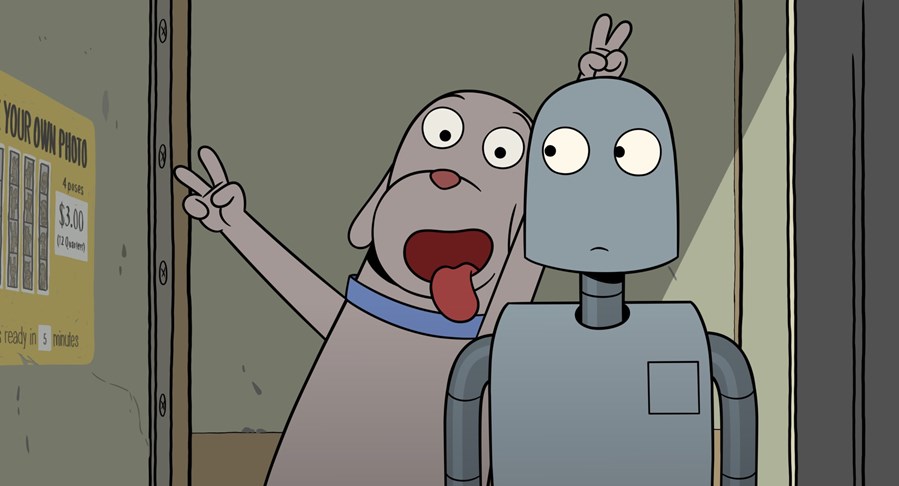

Within the time-consuming world of feature-length animation, the role of the animation director falls between the three poles of creation, coordination and communication: managing the team of animators, liaising with production managers to keep proceedings on schedule and within budget, and also translating the dreams of the director into animated reality. In the case of Robot Dreams, the latter was key. Berger came to the production with a surfeit of ideas. The sweep of Varon’s story remained intact, as did her warm, emotionally engaging art style, but the adaptation grew and grew. While still a sensitive reflection on the passing of time, the film became a visually extravagant tribute to New York City, which Berger once called home, with 400 fully realised background animal characters populating a dense evocation of 1980s Manhattan. It also developed into a consummate celebration of silent cinema, comic books and animation as creative mediums; the film takes inspiration from the simple emotional power of Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931), the clean lines and flat colours of Hergé’s Tintin books and the masterful storytelling touch of Studio Ghibli, whose films take their time and have faith their audiences will follow along.

Robot Dreams (2024)

To that end, Berger wished to pare back the movement of both the camera and the characters, doing away with exaggerated mannerisms and ‘overacting’ that he says is common in more mainstream animation, all with the aim of drawing the audience further into the drama of the story. ‘That’s what is great about cinema,’ Berger elaborates. ‘The film doesn’t have dialogue, the characters are very simple. So it gives the audience space to complete the film themselves.’

Of course, ‘less is more’ is easier said than done, especially when you’ve exchanged live actors for the hand of an artist. ‘Pablo wanted to lessen the expression as much as possible,’ remembers Feroumont. ‘I was really impressed by the way he would fine-tune things. We would work until a certain feeling appeared: the emotion is super clear, super simple, super evident.’ Particular attention was given to the characters’ eyes: the windows to the soul of the film. Berger requested that blinking be kept to a minimum – inadvertently removing one of the fundamental techniques that animators use to breathe life into their drawings. The team, therefore, had to innovate. Feroumont and key animator Jorge Pozo developed a menagerie of micro-expressions, from a crease of the brow to a wrinkle of the nose. ‘They were little tricks, really tiny, tiny things. You see the face of Dog in certain shots, and he’s not moving, but… there’s a little something there bringing him to life.’

Robot Dreams (2024)

Berger admits that he’s a control freak, and working in animation gave him a whole new level of control. After all, where else can you so easily adjust the pupils of characters with pixel-perfect precision? Or insert blink-and-you’ll-miss-it Easter eggs into every frame, from the records lining Dog’s shelves, to background characters designed in homage to famous New Yorkers past, such as Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee and Jean-Michel Basquiat? ‘I like to cook slowly on my films,’ says Berger. ‘I realised, “Wow, this is amazing because here, I can control every detail.” You work in a very precise way. And for me, that was very satisfying.’

Animation can be a perfectionist’s medium. Anything is possible – up to a point. ‘In animation, you have to think about everything, because you have to create everything,’ Feroumont explains with a laugh. ‘So for Pablo, it was a dream come true. And my job was to say no, in a good way!’ Describing his task of finding a balance between the ambitions of a visionary director and the demands of production, Feroumont paraphrases the late Richard Williams, the Academy Award-winning master animator (Who Framed Roger Rabbit, 1988) and author of what is widely regarded to be the foundational textbooks on animation technique, The Animator’s Survival Kit (2001). When making animation, you can tinker with a single shot for a lifetime. Therefore, the most important decision is deciding when to stop, move on, and share your dreams with the outside world.

Robot Dreams is in Cinemas from 22 March