For her directorial debut Blink Twice, Zoë Kravitz casts Channing Tatum as a shady tech billionaire who invites a waitress (Naomi Ackie) to his private island, where mysteries await. To mark the release, we’ve gathered 21 of the best, from across 100 years, to highlight how human nature has changed little when it comes to making moolah.

Triangle of Sadness (2022)

Harris Dickinson and Charlbi Dean are an attractive model couple who find themselves aboard a luxury yacht in the company of oligarchs and arms dealers. The staff cannot refuse a request, no matter how bizarre it might be, and the captain (Woody Harrelson) isn’t quite who he appears to be. Everything looks to come to a head during a fine-dining experience. But for a small number of crew and passengers that’s just when their problems begin. Ruben Östlund’s film gleefully courts controversy and takes aim at the hypocrisies of middle-class society. It is both outrageous and outrageously funny.

Metropolis (1927)

Cinema on the grandest scale, Fritz Lang’s visionary epic is essentially a tale about a divided society, with a privileged class whose lifestyle is paid for by the masses who slave away in huge factories. Revolt is in their air and the powers that be set out to quash it. Lang’s film is a technical marvel, and the recent discovery of his original cut also emphasises the power of his storytelling. For those watching the film for the first time, the home of the wealthy might resemble a kitsch take on a prelapsarian idyll. But Lang’s vast sets depicting the working lives of the proletariat are a sight to behold.

American Madness (1932)

Frank Capra made a number of films about wealth and its impact on family, from Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) and You Can’t Take It With You (1938) to the classic It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). With this earlier film, he details the attempts by an honest banker – a term notably absent in recent conversations about the finance industry – to stem a rumour that threatens to topple the company’s security. It’s a film that questions the value of money for its own sake and over the interests of the many. Capra was no socialist, but he saw the benefits of levelling up across the whole of society.

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Oliver Stone’s era-defining Wall Street (1987) used to rule the roost when it came to depictions of the heart of the US financial markets. But that film’s morality never convinced, as Stone appeared too enamoured with the story’s antagonist Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas). Martin Scorsese’s take on Jordan Belfort’s self-satisfied memoir goes further than Stone. It embraces the world Belfort (played by an uproariously funny Leonardo DiCaprio) created for himself and revels in his antics; not because it sides with him, but because Scorsese and screenwriter Terence Winter believe that to truly comprehend Belfort’s motivations, one must understand the attraction of this world. The Wolf of Wall Street is both a comic masterpiece and a story of excess that rightly becomes too much to bear with its fistfuls of cocaine, performing apes and office debauchery. In the end, Scorsese pulls away to reveal Belfort as nothing more than a cheap showman whose only skill is an ability to fool people.

The Bling Ring (2013)

Adapted from Nancy Jo Sales’ Vanity Fair article ‘The Suspects Wore Louboutins’, Sofia Coppola’s entertaining film details how the eponymous gang of teens kept online tabs on a group of celebrities in order to rob their homes when they weren’t there. The film attracted some controversy for its morally ambiguous perspective. However, like Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, the film attempts to take its audience into the lives of these characters to understand the pathology that led to their actions. The fault, the film implies, ultimately lies with a wider culture that pushes people to want more, often at any cost.

Citizen Kane (1941)

One of the greatest cinematic studies of the corrosive nature of power, Orson Welles’ astonishing feature debut tells the story of Charles Foster Kane, the heir to an oil fortune whose desire to highlight the world’s iniquities soon runs afoul of his need to dominate every aspect of his professional and personal existence. Loosely based on the life of media magnate William Randolph Hearst, Welles’ film is technically and narratively dazzling. It’s also a fascinating exploration of corruption.

Trading Places (1983)

Dan Ackroyd is a blue-chip member of New York’s elite. Eddie Murphy has survived on the street. They become subjects of a wager-cum-social experiment by Ralph Bellamy and Don Ameche’s ageing Wall Street tycoons, who overturn their lives for a $1 bet. It’s a simple set-up for a life-swap comedy that pits the vices of greed against the virtues of decency. It was presaged by the Dudley Moore vehicle Arthur (1981), and followed by Richard Pryor in Brewster’s Millions, which dealt with similar themes. But neither was as smart nor as timely as Landis’ exuberant, endlessly quotable film.

The Great Gatsby (1949)

If you’re looking for a version of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic tale of excess in the Jazz Age that revels in extravagance, then go to Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 adaptation. But this version, the second of four produced for the big screen, is arguably the best. It mostly works because of Alan Ladd’s portrayal of Jay Gatsby. Better known for his Western and film noir roles, Ladd captures the ambiguity of Gatsby’s titular character and the weight that wealth places upon him.

The Exterminating Angel (1962)

Having spent a night at the opera, Mexico City’s rich set enjoy a dinner hosted by socialites Edmundo and Lucía Nóbile in their mansion. Before long, everyone retires to the couples’ salon. Odd things have been happening all evening, such as the servants deciding to take off for the night. But that pales compared to the increasing anguish felt by the guests when they realise they cannot leave the salon. There’s no physical impediment, but a stasis in their social positioning – an unwillingness for them to change that might affect the comfort of their existence – has led to this strange condition. Hours turn to days, then weeks, and the guests descend to instinctive and – certainly for refined society – unbecoming behaviour. Luis Buñuel’s satire is a perfect takedown of wealth and privilege, and the spiritual ancestor to Ruben Östlund’s cinema.

Parasite (2019)

A tale of two families: one rich, the other considerably less so. Their paths cross when a favour for a friend finds the poorer family entering the employ of the rich one, albeit without that family’s knowledge that the people taking care of them are related. But a housekeeper recently fired by the wealthy family can’t stay away – her reasons become clear one stormy night. The international success of Bong Joon Ho’s film – which became the first foreign-language movie to take home the Best Picture Oscar – not only lies in its technical and narrative brilliance, but in the growing concern over economic disparity between rich and poor around the world.

The Godfather Part II (1974)

Part of the genius of the second part of Francis Ford Coppola’s mafia saga – whether it’s the best in the series remains open to debate – is the way he links the dream of acquired wealth with notions of family. The film’s celebrated flashbacks are not randomly constructed; they play out associatively as part of a commentary on Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro’s) rise and his burgeoning family, and his son Michael (Al Pacino’s) securing power at any price and the crumbling of his domestic life. Some see elements of Marxism in Coppola’s strategy. There is little doubt, though, that his film regards the rampant acquisition of wealth not as the objective of the American Dream but its Achilles heel.

Grey Gardens (1975)

In the golden age of classical Hollywood cinema, countless films featured old money. Katharine Hepburn, herself a scion of an established East Coast family, was the star of many of them. Had we stayed with one of her characters – Tracy Lord from The Philadelphia Story (1940) perhaps, or even better, Susan Vance from Bringing Up Baby (1938) – would they have ended up like Edith or ‘Little Edie’ Bouvier, the stars of this astonishing documentary? Grey Gardens has a rich history. Lee Radziwill, sister of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, wanted to make a film about her eccentric cousins, who lived in a dilapidated house in a quaint East Hampton village. That venture fell through. The Maysles, who had been employed on that film, decided to make their own documentary. Working with Ellen Vovde, this is the result. It’s quite unlike any other film. There’s no narrative to speak of, just the mother and daughter reminiscing about times past and Edie’s aspirations to become a singer. It’s a singular study of the eccentricity that wealth can afford.

The Big Short (2015)

Few non-fiction writers have chronicled US and global financial markets and the culture that exists around them as successfully as Michael Lewis. From his outrageous debut Liar’s Poker (1989), detailing his personal experiences on Wall Street, to the jaw dropping Flash Boys (2014), which posits that the markets are far more unfair than people realise, Lewis has proven himself a witty and knowing guide. His account of the financial debacle that became the 2008 economic crisis – the events that led up to it and its immediate fallout – was an instant bestseller. Adam McKay’s film manages to take all the book’s disparate narrative strands and channel them into a cohesive film that conveys the complexity of the world Lewis documented, while also offering a scathing diatribe against a system that has no regard for the cost of its actions provided those at the top keep earning.

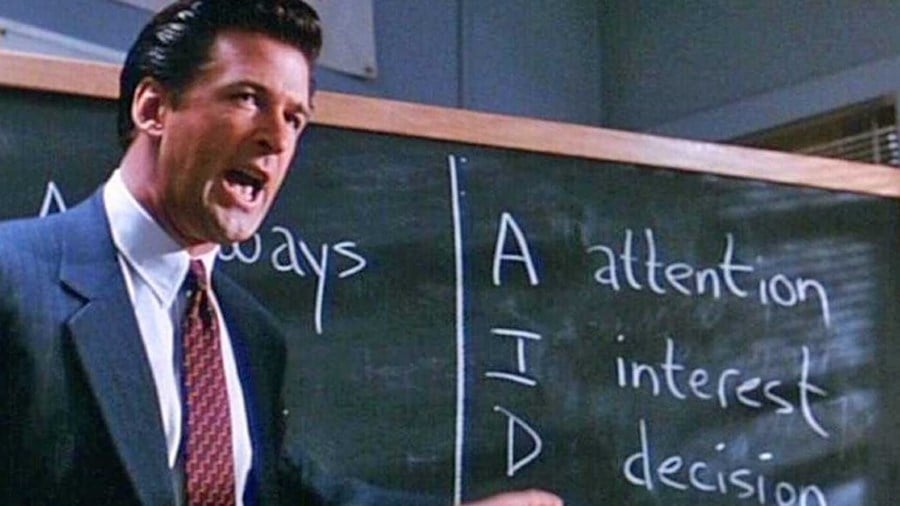

Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Early in this adaptation of David Mamet’s acclaimed stage play, Alec Baldwin’s executive ‘from downtown’ tears each salesman occupying a small office a new one, berating them for their poor performance. It’s a masterclass in intimidation, bullying and petty macho aggrandisement. It also gets to the kernel of Mamet’s play – the ugly side of the American Dream. Like Eugene O’Neill with The Iceman Cometh (1939) and Arthur Miller with Death of a Salesman (1949), Mamet’s play offers a brutal portrait of the bottom end of the capitalist structure. It would be insufferably nihilistic were it not for Mamet’s writing and a starry cast featuring Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon, Ed Harris, Alan Arkin, Jonathan Pryce and Baldwin at their splenetic best. It’s electrifying.

Hyenas (1992)

Can anything be bought? That’s the question asked by the residents of Colobane, a village on the outskirts of Dakar, when they’re visited by a wealthy woman who once lived there and who has returned to take vengeance on a sleight she suffered in her youth. Djibril Diop Mambéty’s second and final feature, produced some two decades after his acclaimed debut Touki Bouki (1973) and adapted from Swiss writer Friedrich Dürrenmatt's play The Visit (1956), presents a fascinating moral conundrum. How much is a human soul worth; not just the soul being taken, but the one being bought to carry out the act? Mambéty’s niece, actor-director Mati Diop, would explore similar terrain, albeit through the prism of economic migration, with her assured 2019 debut Atlantics.

American Psycho (2000)

Brett Easton Ellis’ controversial novel was deemed unfilmable. Mary Harron’s masterstroke was to excise the book's excessive violence – nevertheless, it’s still pretty violent – and to play up its satire. Christian Bale kick-started his adult acting career with a superb performance as Wall Street executive and possible serial killer Patrick Bateman. His voiceover balances deadpan delivery with the right amount of ennui of a young man already bored by existence and looking for any kicks to excite him. It loses none of Ellis’ shock factor, while jettisoning the perceived misogyny of the book. It’s also very, very funny.

Snowpiercer (2013)

Before Parasite, Bong Joon Ho delivered this high-concept slice of science fiction. Chemicals have destroyed the world, turning every corner of it into a frozen tundra. The last vestiges of humanity exist on a train that travels perpetually along an interconnected track that circles the globe. Life aboard it resembles the social structures of capitalist societies; the elite live in the lap of luxury in the carriages towards the front of the train, while the worker class slave away in cramped conditions at the back, with nothing to sustain them save for an apparently nutritious black jelly that’s doled out sparingly. But revolution is afoot. Most of the film is taken up with the rebels fighting their way, carriage by carriage, to the front of the train. But a surprise lies in store. Bong regular Song Kang-ho holds the secret to the journey to the engine, while Chris Evans leads the attack and Tilda Swinton has a whale of a time as the train’s officious administrator. It’s a dazzling and – rare for a blockbuster – intelligent ride.

Crazy Rich Asians (2018)

This adaptation of Kevin Kwan’s popular novel is all light and confection, and went on to become the largest grossing Hollywood romantic comedy of the 2010s. It was also the first Hollywood film to feature a majority cast of Chinese descent since Wayne Wang’s 1993 drama The Joy Luck Club. Set among East Asia’s wealthy elites, it sees Rachel (Constance Wu) meet her boyfriend (Henry Golding’s) family for the first time, not realising quite how rich they are. Sweet, funny and bolstered by incredible costume design, the film was considered a step forward for screen representation.

Generation Wealth (2018)

A major multimedia project, spanning an installation and book alongside this film, Generation Wealth can be seen as the second in a trilogy of films by Lauren Greenfield dealing with money-obsessed societies around the globe. First there was The Queen of Versailles (2012), about a wealthy real-estate magnate who decides to build the largest domestic property in the US just as the global economy sinks in 2008. Then, in 2019, Greenfield released The Kingmaker, a portrait of Imelda Marcos, former First Lady of the Philippines. It’s an unsettling look at the intersection between political power and unfettered greed. Generation Wealth is a wider portrait of the desire for wealth among a disparate collation of individuals in societies around the globe. Greenfield even turns her camera upon herself. The result is a barometer of how consumerism has become all-encompassing and acquiring money for its own sake has taken on the attributes of a contagious virus.

New Order (2020)

A high society wedding in Mexico City, with members of the ruling party present, takes place just as trouble appears to be stirring among the less fortunate members of the local populace. But what initially appears to be a series of spontaneous eruptions of violence and rioting soon transforms into a skilfully coordinated revolution. It becomes clear that those leading the charge are merely puppets for an order hell-bent on keeping control. And that powerful cabal understands that, to maintain power, the aggrieved in society need to let off a little steam now and then. Michel Franco’s deeply disturbing film is all too believable – it plays out like a chapter from Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine (2007), which details how governments use crises to increase their control over society. Even if it revels a little too much in the violence of this world, it's to Franco’s credit that he has made a film that is uncompromising in every way.

Azor (2021)

Argentina in the mid-1980s was under the authoritarian rule of a corrupt military regime. But there was money to be made, and private banker Yvan de Wiel (Fabrizio Rongione) arrives from Geneva with his wife Inès (Stéphanie Cléau) to continue the work of his partner, who has mysteriously disappeared. Doors are initially closed to him. But as he proves his ability to work discreetly, Yvan finds himself drawn into the inner circle of an elite working in conjunction with the regime in order to shore up its own interests. Just as JC Chandor’s feature debut Margin Call (2012) ably engineered a dramatic account of what led to the 2008 financial crisis, so Andreas Fontana’s extraordinarily accomplished first film creates an all-too-believable world of country-club wheeler-dealings. And the film’s final sequence chills the heart.

WATCH BLINK TWICE IN CINEMAS