Since its emergence in 1985, Studio Ghibli – the title comes from the Libyan Arabic name for ‘hot desert wind’ – has become one of the leading animation houses in the world. It is dominated by the work of filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki, along with co-founder Isao Takahata. Emphasising quality over quantity, each release by Studio Ghibli has become a major event. With the rerelease of Miyazaki’s My Neighbour Totoro coming up, we’ve compiled a list of the finest Ghibli releases.

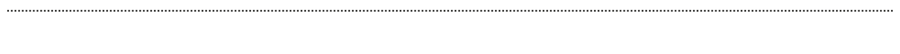

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Strictly speaking, Nausicaä isn’t a Studio Ghibli film. It was as a result of this film’s huge commercial success that Ghibli came into existence. Unfolding 1,000 years after a cataclysmic war that transformed the Earth into a toxic wasteland, the film follows a princess as she attempts to save mutated wildlife from human forces. Referred to as ‘anime’s answer to Dune’, the film is wildly imaginative and began a career-long collaboration between Miyazaki and composer Joe Hisaishi. It also featured an environmental theme that would become a constant throughout so much of the filmmaker’s work.

Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986)

Miyazaki traded in his eco-dystopia for a fictional late-19th-century world. Drawing on the landscape of the Welsh mining valleys that he visited shortly before production, as well as Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) and elements of his earlier anime series Future Boy Conan (1978), Miyazaki tells the tale of a young girl, in possession of a crystal that bestows remarkable powers on her, who journeys to a magical floating kingdom. Like Nausicaä, Laputa is a breathtaking feat of imagination, realised via beautiful, hand-drawn animation. The impressive opening-credit imagery even echoes Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 painting The Tower of Babel.

Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

Takahata had been directing films since the late 1960s and was hugely influenced by the French New Wave. His first film under the auspices of Ghibli was his international breakthrough. It is also one of the studio’s bleakest films. Unfolding in the aftermath of the US bombing of Kobe in 1945, Grave of the Fireflies finds siblings Seita and Setsuko adrift in a barren world following their mother’s fatal injury. They attempt to survive in a land devastated by war, but life becomes too much of a burden for them. Now hailed as one of the finest war films ever made, Grave of the Fireflies is an uncompromising vision of inhumanity, leavened by the compassion of the main characters.

My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

Studio Ghibli cemented its reputation with Miyazaki’s first bona fide masterpiece. Featuring the titular spirit character that gave the studio its logo, My Neighbor Totoro is set shortly after World War II, when young sisters Satsuki and Mei move with their father to the countryside. Mei, four, befriends a benevolent tree spirit, whose name she believes to be Totoro. Gradually, the spirit and its cohorts comfort both girls as they await news of their ailing mother, even taking them on an adventure. Animism would play a significant role in many of Miyazaki’s films and here it’s put into the service of a heartwarming tale that once again highlights the filmmaker’s incredible imagination.

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

The first of Miyazaki’s profession films, in which a character’s vocation is indelibly linked to their character and the narrative that unfurls, Kiki’s Delivery Service tells the story of young witch who sets up a delivery service with the help of her talking cat and witch’s broom. Exploring the relationship between tradition and modernity, as well as the challenges of nearing adulthood, the film may not have the majesty of Totoro, but Miyazaki invests the film with such joy and affection, it’s impossible not to be won over by it.

Only Yesterday (1991)

Compared with the films that bookend it, Takahata’s slow-burn, understated character study might seem prosaic, if it weren’t so lovingly produced. The biggest film at the Japanese box office in 1991, Only Yesterday finds 27-year-old Tokyo resident Taeko Okajima taking time off from work to visit her sister’s in-laws in the countryside. The train journey sparks memories of her childhood, and the entire trip finds Taeko moving between the present and a recalled past, in an attempt to figure out where her life is heading. In a lesser director’s hands, the film might have drowned in mawkish sentimentality. Instead, Takahata produces a winsome portrait of a young woman coming to terms with the road her life has taken.

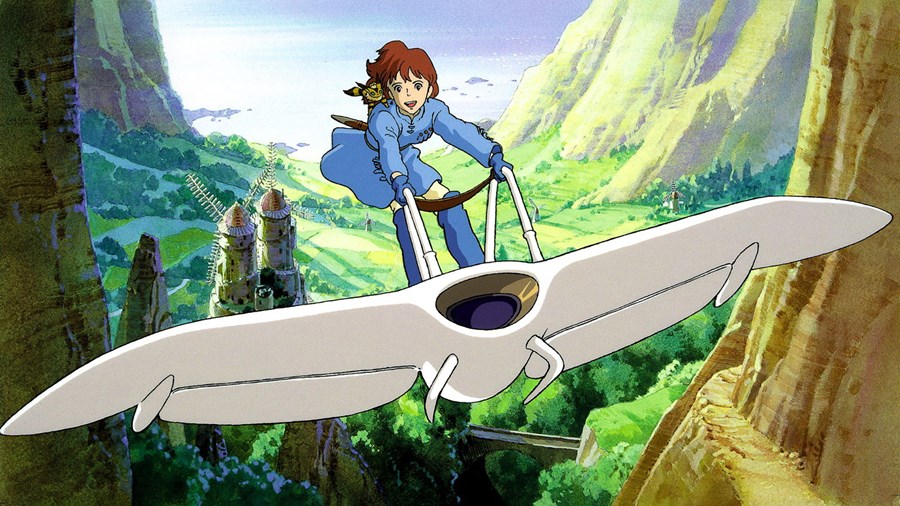

Porco Rosso (1992)

Another profession film, but this time one that bristles with a different kind of energy to Kiki. The titular hero is a gruff, obstinate Italian pilot, a former military ace who garnered an impressive reputation during World War I. He is also a pig, the result of a strange curse, who now battles ‘air pirates’ in the skies. It was originally intended as a short for Japan Airlines, but Miyazaki instead decided to adapt his 1989 manga The Age of the Flying Boat. His impressive handling of action sequences would give some hint of the greatness that was to come with two of his most acclaimed films, later in the decade.

Whisper of the Heart (1995)

Following Tomomi Mochizuki’s TV film Ocean Waves (1993) and Takahata’s commercially successful Pom Poko (1994), Whisper of the Heart was another hit for the studio. The feature debut of Yoshifumi Kondō, written by Miyazaki, it tells the story of a young girl who develops her gifts as a writer while befriending – and ultimately falling in love with – a boy who encourages her creative gifts. Both Takahata and Miyazaki saw the slightly younger Kondō as the gifted filmmaker who could take over Ghibli from them. But it was not to be. Kondō died suddenly from an aneurysm in 1998. A spin-off from this film, The Cat Returns, was released in 2002.

Princess Mononoke (1997)

A monumental work, in which Miyazaki’s skills as a writer and director achieve dizzying new heights, Princess Mononoke is seen by some as Studio Ghibli’s crowning achievement. An environmental parable, Miyazaki’s fantasy, about the battle between nature and an increasingly voracious industrialised society, is thrilling, moving and, through its bold use of colour, frequently breathtaking. Unfolding during Japan’s late Muromachi era (approximately 1336-1573), the struggle between the gods of the forest and the humans seemingly hell-bent on destroying the natural world is as fully realised as any fantasy novel, with the narrative’s real-world environmental concerns giving it a gravity most animated – or live-action – films would kill for.

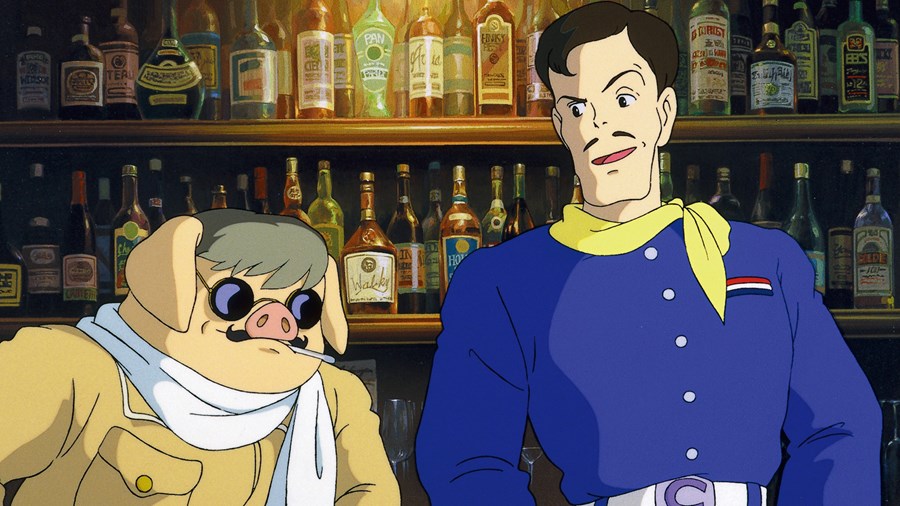

My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999)

Bookended by two heavyweight Ghibli features, Takahata’s singular film is a minor delight. The first completely digital film by the studio, My Neighbors the Yamadas’ series of interconnected stories is comic strip in style, marking a contrast to pretty much everything else the studio has produced. Revelling in the whimsy of daily family life, it’s charming and funny.

Spirited Away (2001)

A contender, alongside Totoro and Mononoke for the greatest Ghibli film, Miyazaki’s Oscar-winning take on an Alice in Wonderland fantasy is overflowing with invention. From the moment young Chihiro realises her parents have been turned into pigs, we journey with her into a world of witches and spirits. There are so many highlights, from the multi-limbed bathhouse boiler operator and mud-caked spirit to the transformation of Chihiro’s new friend Haku into a dragon. And it’s all accompanied by Joe Hisaishi’s lush score, arguably his best for Miyazaki, ranking alongside his finest collaborations with Takeshi Kitano (Hana-Bi, Kid’s Return, A Scene By the Sea).

Howl's Moving Castle (2004)

Miyazaki cemented the worldwide success of Spirited Away with this loose adaptation of popular children and YA writer Diana Wynn Jones’ 1986 novel, about a young girl, Sophie, who is transformed into a 90-year-old woman by a witch. In order to break the spell, she agrees to help free a fire demon from the auspices of the Wizard Howl, whose magical, moving castle he powers. If Howl’s narrative lacks the wonder of Miyazaki’s previous two works, the filmmaker’s visual prowess remains at its peak, creating a spellbinding world. The film also evinces a strong anti-war message, which represented Miyazaki’s opposition to the 2003 US invasion of Iraq.

Tales From Earthsea (2006)

As far back as Nausicaä, the influence of American speculative fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin was evident in Hayao Miyazaki’s work. It was obviously a family obsession, as his son Gorō made his directorial debut with this film, which draws from the first four novels in Le Guin’s Earthsea series, as well as his father’s 1983 manga Shuna’s Journey. Le Guin was unhappy that Miyazaki senior wasn’t directing (as was the filmmaker himself, who noted publicly that he felt Gorō might not have the experience needed to pull off such an ambitious project) and if the end result is middling within the Ghibli canon, it’s impossible not to be impressed by the scope of the film’s vision. The director followed it with From Up on Poppy Hill (2011) and Earwig and the Witch (2020), neither of which are as impressive as this film.

Ponyo (2008)

If films like Mononoke, Spirited and Howl are likely to unsettle younger audiences, with their dark themes and occasionally grotesque characters, Ponyo is Miyazaki’s cinematic olive branch to infant audiences. Few of Ghibli’s films can match the sheer exuberance of this film, whose colours pop off the screen and whose tale is friendly to audiences of any age. A once human wizard lives in the sea with his daughters. The eldest, Brunhilde, becomes trapped in a glass, floats ashore and is found by a young boy, Sōsuke. It is the start of a friendship that helps define the film’s subtle environmental message.

The Wind Rises (2013)

In 2009, Miyazaki published the short manga The Wind Rises, about fighter designer Jiro Horikoshi and his creation of the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter plane. An aerial obsessive, he revelled in the wonder of flight through his artwork. The project soon morphed into Miyazaki’s next film, which he thought was to be his last. Although it’s about a designer who creates a plane that becomes perfect as a weapon, The Wind Rises is very much a work of pacifism and quite unlike any of the writer-director’s previous films.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013)

Takahata’s final film – he died in 2018, aged 82 – is a glorious, creatively original interpretation of the 10th-century story, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. The titular character is a lowly member of society who makes a startling discovery while working in the fields – one that transforms his and his wife’s lives. Employing watercolour backdrops and a simple, sketched character style, the artwork gives the film a fragility that reflects the sense of wonder that permeates the story. It's a rhapsodic swansong from a great filmmaker.

When Marnie Was There (2014)

In 2010, long-term Ghibli animator Hiromasa Yonebayashi made his solo directorial debut with Arrietty, an adaptation (by Miyazaki and Keiko Niwa) of novelist Mary Norton’s 1952 children’s classic The Borrowers. It was bright and breezy. His follow-up is a more complex and fascinating film. Taking on Joan G. Robinson’s 1967 novel, it tells the story of Anna, who is sent to the countryside following an asthma attack and befriends a girl her age, whom she comes to realise is a ghost from the past. Yonebayashi skilfully creates an ethereal, though never scary, atmosphere, drawing us into Anna’s world and gradually revealing the history of the environment that fascinates the girl.

How Do You Live (2023)

Studio Ghibli is renowned for its secrecy. All we know so far about the film that brought 82-year-old Miyazaki out of retirement is that it is a loose adaptation of the 1937 bildungsroman by novelist Genzaburo Yoshino that has long been a part of Japan’s literary canon for young students. The Japanese release date is July. The worldwide release should follow shortly after. It’s one of the most eagerly anticipated films of the year and will be Hayao Miyazaki’s last. Well, for now, at least.

WATCH MY NEIGHBOUR TOTORO IN CINEMAS