A breakdown of the most superlative work from the master himself: Martin Scorsese.

Over the last 50 years, Martin Scorsese has proven himself one of the most extraordinary filmmakers in the history of cinema. A cinephile with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the medium, he has produced a body of work steeped in the quandaries of faith, displaying a fascination with masculinity and our propensity for violence – both physical and spiritual. Scorsese’s cinema is, by turns, visceral, emotionally rich and endlessly rewarding. With his latest feature, Killers of the Flower Moon, premiering at Cannes Film Festival, we look back on Scorsese’s hallowed filmography, celebrating a master whose technical virtuosity is matched by a visual poetry that few directors have equalled.

Mean Streets (1973)

This is the Scorsese blueprint, where the career he’s revered for really began. Harvey Keitel, who featured in his feature debut, again takes the lead. He plays Charlie Cappa, a resident of New York’s Little Italy, whose life skirts the fringes of organised crime. A devout Catholic, Charlie is having an affair with Teresa, the cousin of his devil-may-care friend ‘Johnny Boy’ Civello, played by Robert De Niro in his first collaboration with Scorsese. The actor and filmmaker spark off each other – the first proper scene with De Niro’s character is played out in slow motion, in a red-lit bar and to the strains of The Rolling Stones’ ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ (The Stones, of course, are another mainstay in Scorsese). It’s here that the filmmaker’s directorial career really takes off, and where De Niro began his ascent as one of cinema’s greatest actors.

Goodfellas (1990)

Scorsese’s portrait of mobster Henry Hill is a wild, dazzling, disturbing and riveting tale. Ray Liotta, Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Lorraine Bracco lead the cast, playing Hill, his hoodlum friends Jimmy Conway and Tommy DeVito, and wife Karen, bringing grit to their roles. Thelma Schoonmaker’s snappy editing keeps the pace brisk, as Scorsese’s camera keeps on the move, whether it’s a magisterial – and celebrated – tracking shot through a restaurant, or a drug-addled car journey in the film’s later stages. Scorsese never judges his characters, but neither does he lionise them. It’s frequently funny, while always reminding us that these are violent, frequently dangerous and – as Pesci’s Tommy makes abundantly clear – borderline psychotic individuals.

The Departed (2006)

The film that finally saw Scorsese win an Academy Award. His remake of the 2002 crime thriller Infernal Affairs – relocating the action from Hong Kong to Boston – is an improvement on the original, which came up with the brilliant cat-and-mouse scenario of an underworld boss with a mole in the police department at the same time that law enforcement has an undercover cop close to the gangster. Leonardo DiCaprio, in his third film with Scorsese, is the undercover cop. Matt Damon is the mole in the police department. Jack Nicholson, at his charismatic best, is the hoodlum. And Martin Sheen plays DiCaprio’s handler. But trumping them all is Mark Wahlberg as a splenetically foul-mouthed loose cannon of a police sergeant.

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)

One of only three films – along with Boxcar Bertha (1972) and New York, New York (1977) – to feature a female protagonist, this stars Ellen Burstyn as a former singer and mother who decides to return to her career after the death of her husband. Financial woes find her waylaid in Arizona, where she has a brief but violent affair with Harvey Keitel’s loser. In Tucson, she meets Kris Kristofferson’s rancher, who promises stability, but at what cost? Coming off the back of a star-making performance in The Exorcist (1972), Burstyn never hits a wrong note as Alice, which saw her awarded with a Best Actress Oscar. It’s a low-key delight, a character-driven piece that diverges from Scorsese’s outré subsequent work. It highlights his development as a filmmaker of great emotional depth.

The Color of Money (1986)

Less a sequel than a ‘what happened to…’ drama, The Color of Money catches up with Paul Newman’s ‘Fast Eddie’ Felson some 25 years after his battles with Minnesota Fats in The Hustler (1959). He teams up with Tom Cruise’s upstart Vincent Laurie, a promising young pool shark who Eddie believes could become as brilliant as he once was. Newman won an overdue Best Actor Oscar for his performance, which conveys the battered spirit of a man who has weathered life rather than lived it. Cruise dazzles in his first serious role, offering a scene-stealing turn that exudes star quality. Scorsese and Schoonmaker have fun creating drama on and around the pool table, coming up with sequences that are no less breathtaking in their ingenuity than those that unfold in Raging Bull’s boxing rings.

Taxi Driver (1976)

A tempest of angst and torment, Taxi Driver has lost none of its power. Robert De Niro is outstanding as disturbed Vietnam vet Travis Bickle, who takes a job as a cab driver in New York, choosing to work through the night and raging, via screenwriter Paul Schrader’s words, against the world. It’s a frightening portrait of urban chaos that comes to an explosive climax as Travis attempts to ‘save’ Jodie Foster’s underage prostitute from the streets and Harvey Keitel’s sleazy pimp. The score, the last by the great Bernard Hermann of Vertigo (1958) fame, shifts seamlessly between a state of unease and a mellifluous romanticism that evokes a world gone by. Michael Chapman’s cinematography is both gleaming and dirty as it captures Bickle’s cab prowling through the night. And Marcia Lucas’ editing, particularly in the bloody climax, is near-perfect. But the stars here are De Niro and his intensity, Schrader and his dark worldview, and Scorsese, who employs his immense talent to create a world that is both terrifying and exhilarating.

After Hours (1985)

As close as Scorsese has ever got to an out-and-out screwball comedy, After Hours has some of The King of Comedy’s nervous energy, but it’s leavened by a little more light as it journeys through one New York night. Griffin Dunne plays an office worker who, through a series of mishaps, gets lost in the city, encountering oddballs and finding himself trapped in bizarre situations. Not as well-known as it should be, the film fit neatly in the ‘yuppie nightmare’ group of films that appeared around this time.

New York, New York (1977)

Scorsese’s anti-musical riffs on the golden age of song and dance with a portrait of post-war New York that throbs with energy and malevolence. The narrative revolves around the off-on-off relationship between Liza Minnelli’s talented singer and Robert De Niro’s gifted but destructive saxophonist. They can’t seem to live without each other, yet together they’re radioactive. With seductive visuals and a title track that would become a signature song for Frank Sinatra, New York, New York has all the ingredients for a classic. But Scorsese’s desire to explore the darker side of showbusiness creates a compelling mood piece.

Raging Bull (1980)

Robert De Niro, in his Best Actor Oscar-winning role, delivers an extraordinary performance that saw him bulk up to be a prize fighter and then gain a staggering amount of weight to play Jake LaMotta in later life. (Production actually ceased on the film for a couple of months for De Niro to go to Italy and put on the necessary pounds.) He’s matched by sterling work from Joe Pesci as his brother Joey, newcomer Cathy Moriarty as Jake’s second wife Vickie and Frank Vincent as Salvy Batts. Scorsese’s directorial style hits new heights: each fight is shot in a different way, and all are breathtaking. Perhaps the most important partnership in the film is the one between Scorsese and an editor he had known since they worked together on his 1970 documentary Woodstock, Thelma Schoonmaker. It’s impossible to overstate the importance of her role in all of Scorsese’s features from this point on. She won the first of her three Oscars for her work on this film.

Gangs of New York (2002)

Gangs of New York ranks high in the list of ‘how in God’s name did they get the money to make that?’ movies. It charts the development of New York, from a denizen of thievery and iniquity in the mid-19th century to a more ‘civilised’ world. Central to it is the real-life figure of William ‘Bill the Butcher’ Cutting, played with wild-eyed relish by Daniel Day-Lewis. Leonardo DiCaprio is Amsterdam Vallon, whose priest father was killed by Cutting in a street battle. With vengeance on his mind, Amsterdam nevertheless finds himself drawn into Cutting’s world. Unfolding on an operatic scale, Scorsese’s film is both a bloody history lesson and the pugnacious, unruly sibling of The Age of Innocence. There’s no denying the bravura of bringing such a world to the screen and on such a monumental scale.

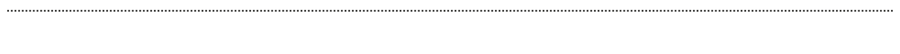

The King of Comedy (1982)

Scorsese’s hilarious, disturbing and pathologically madcap The King of Comedy captures the unhealthy obsession of fandom. De Niro’s Rupert Pupkin, apparently the only portrayal the actor cannot bear to rewatch, is a wannabe TV comedian. He is fixated on Jerry Lewis’ late-night talk-show host and, along with Sandra Bernhard’s equally fanatical admirer, decides to kidnap him. Pupkin exists on the same spectrum as Travis Bickle, albeit minus the violence. But his obsessions are no less consuming. It’s a bold performance by De Niro – one of his best – which has only come to be appreciated, like the film, with the passage of time.

The Age of Innocence (1993)

A complete surprise. If Goodfellas and Cape Fear were driven by a visceral, physical violence, Scorsese and Jay Cocks’ adaptation of Edith Wharton’s 1920 novel details a society in which emotion is the sharpest weapon. Daniel Day-Lewis is Newland Archer, a scion of New York high society who is betrothed to Winona Ryder’s ingénue May Welland. But his life is thrown into tumult when he encounters Michelle Pfeiffer’s Ellen Olenska, an enigmatic Countess and divorcée whom Archer initially befriends because of the way she is treated like a pariah by his peers. But courtesy soon turns to passion and Archer’s world threatens to implode. The cast is sublime, while Scorsese’s recreation of the era is a sight to behold. It’s the way he captures the oppressiveness of this world that makes The Age of Innocence so outstanding. Playing with the fortunes of people’s lives like a game of roulette, the society Scorsese brings to the screen is no less monstrous than the very worst of his mobsters.

The Irishman (2019)

This sprawling crime saga, which arrives some five decades into the filmmaker’s career, tells the highly subjective life story of Frank Sheeran, who maintained he was the man who whacked labour union leader Jimmy Hoffa. The film was not only the first collaboration between Scorsese and Al Pacino, who plays Hoffa, it saw the director reunited with Harvey Keitel for the first time since The Last Temptation of Christ and it brought Joe Pesci back out of retirement. It was also the first time De Niro and Scorsese had worked together since Casino, and the actor delivers a towering performance. Much was made of the film’s technological wizardry, de-ageing the actors through the use of sophisticated digital effects. But what’s most impressive about the film is that after more than 100 years of gangster movies, The Irishman approaches organised crime in the US from a wholly unique perspective. Gone is the humour present in much of Goodfellas. In its place is the chill that lies in the film’s portrait of people whose souls have been hollowed out by their actions and all that remains of them is a husk – a shadow of lives that were not worth living.

The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

After almost a decade of development, with various studios nervously backing out at the 11th hour, Scorsese and screenwriter Paul Schrader finally went into production with The Last Temptation of Christ, the first of a loose trilogy of films that deal directly with religion and belief. Willem Dafoe is Christ; Harvey Keitel, Judas and, interestingly – if not entirely successfully – David Bowie plays Pontius Pilate. Controversy surrounding the film lay in the dream sequence that unfolds while Christ is on the cross. But such opposition was misplaced: this is a deeply religious film. And it remains one of the few dramas made about the life of Christ that eschews the myths in favour of an intelligent, if overly earnest, exploration of the nature of faith.

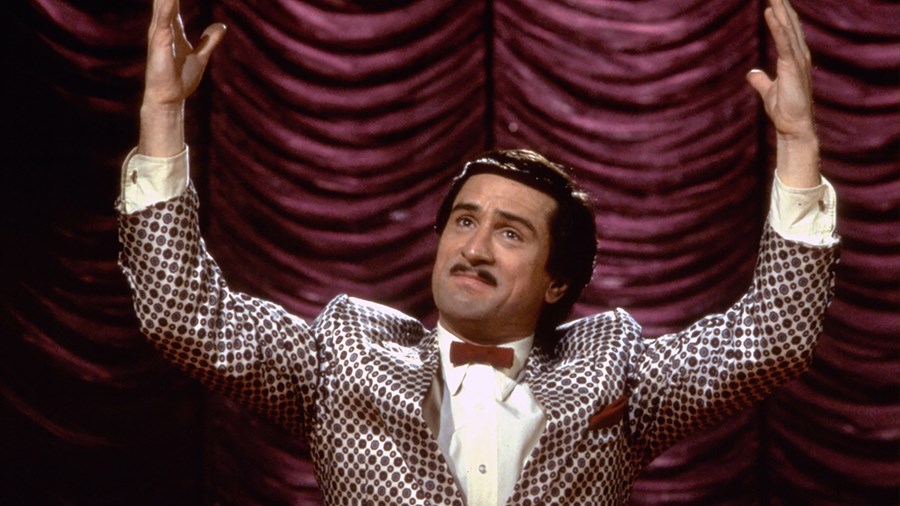

Cape Fear (1991)

This remake revels in the humid, oppressive atmosphere of the Deep South. Nick Nolte is attorney Sam Bowden who, some years before, suppressed evidence in order to secure the conviction of his client Max Cady (De Niro). Now released from prison, during which time he studied law and discovered Bowden’s misdeed, Cady has arrived in the sleepy North Carolina town where Bowden lives with his wife Leigh (Jessica Lange) and daughter Danielle (Juliette Lewis), intent on taking his revenge. Nolte, Lange and particularly Lewis, in her breakthrough role, are all excellent. De Niro, meanwhile, doesn’t so much deliver a performance as chew the scenery around him: his Cady is a ripped, terrifying monster. And a smart one to boot. It’s when Cady’s employing his intelligence, operating the grey zone between the law and illegality, that the film really throbs with energy. The climax is ludicrous – and absurdly enjoyable.

The Aviator (2004)

With Gangs, Scorsese entered the world of the over $100 million budget movie. It’s where he has mostly remained. And with it, the nervous energy of his earlier work has mostly been replaced by a sense of grandeur. Nowhere more so than this elaborate paean to the golden age of Hollywood and a portrait of the eccentric tycoon Howard Hughes (DiCaprio). The bulk of the film unfolds between 1927 and the late 1940s, from Hughes filming his World War I epic Hell’s Angels, to his defeating a Senate investigation into his business interests and flying the gigantic H-4 Hercules plane. It’s unashamedly entertaining seeing Cate Blanchett, Kate Beckinsale and Jude Law play Katharine Hepburn, Ava Gardner and Errol Flynn respectively. It’s similarly thrilling watching Hughes crash-land his plane on the roofs of Beverly Hills mansions – a sequence that guaranteed Thelma Schoonmaker her second Best Editing Oscar.

Casino (1995)

Teaming up again with De Niro and Pesci, this tale of life in the gambling capital of the US is a visual tour de force. From the outset, with De Niro’s character Sam ‘Ace’ Rothstein being blown up in a car, Casino is an exercise in virtuoso filmmaking. But the film’s ace is Sharon Stone, who turns in a charismatic, career-best performance as Ginger Mckenna, Sam’s wife and trouble from the moment she enters his life. There’s also the music. Goodfellas revelled in a soundtrack driven by songs that capture a moment in history. Casino similarly profits from an incredible jukebox of music selections, from Muddy Waters, Roxy Music and Fleetwood Mac to Tony Bennett, Cream, Dinah Washington and, most impressively, Bach’s ‘St Matthew’s Passion’.

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio’s finest collaboration to date is this wild and hilarious take on the life of fraudster and confidence trickster Jordan Belfort. DiCaprio spent much of the previous decade in serious-drama mode, and this film feels like the mother of all releases. If Goodfellas was a pacy journey through a criminal underworld, Wolf is a frenzied rollercoaster ride into the shady dealings of Belfort’s career as a stockbroker. For its three-hour runtime, Scorsese barely allows us a moment to breathe. And along the way, he delivers some of the most hilarious sequences of his career (quaaludes, anyone?). Much like Goodfellas, Wolf doesn’t encourage us to warm to its deplorable characters. But the film does convincingly convey why Belfort and his friends did what they did, and the thrill of doing it.

WATCH KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON IN CINEMAS