Rich Peppiatt’s riotous Kneecap is just the latest film to explore life in Ireland. From both sides of the border, movies depicting the nation have offered a rich portrait of life, past and present, which have engaged with its troubled political situation and looked beyond it. The films in this collection, covering a century of cinema, offer a small sample of the full spectrum of this rich cinema.

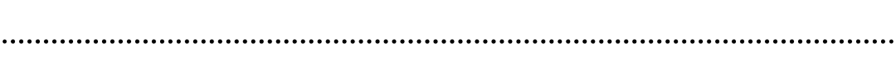

Man of Aran (1934)

Following the success of his Nanook of the North (1922) and Moana (1926), which explored life in the Arctic and Samoa, the director Robert Flaherty turned his attention to a small outcrop of land to the west of Ireland, in the Atlantic. Once again, he melded documentary footage with staged sequences to portray the challenges of life for the island’s small fishing community, creating a film that is both austere and poetic.

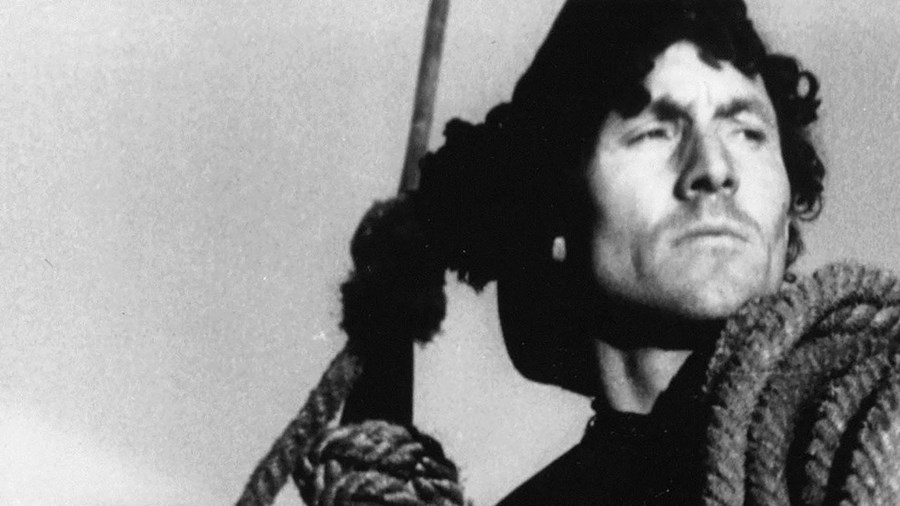

The Quiet Man (1952)

Alongside Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out (1947), John Ford’s film is one of the most popular Ireland-set productions of the period. Where Reed’s film was a dark, morally ambiguous noir-tinged thriller about James Mason’s IRA member on the run, Ford’s is a picturesque portrait of an American coming to terms with his heritage. John Wayne plays a US boxer returning to the place of his birth and falling in love with Maureen O’Hara’s local, much to the chagrin of her father, played by Victor McLaglen. Gorgeously shot, making the most out of the verdant countryside, The Quiet Man is a picture-postcard portrait of Irish life.

The Rocky Road to Dublin (1968)

The Irish-born journalist Peter Lennon’s series of interviews about life in his mother country ranks alongside Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1960) and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Love Meetings (1964) as a barometer of the times. Its conclusions are both bleak and damning. Covering a range of subjects – including politics, the relationship between church and state, and the challenges of everyday life – the film shows a country that seems hell-bent in its resistance to change.

Barry Lyndon (1975)

With his adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon, Stanley Kubrick pushed the envelope of the period drama, just as Tony Richardson had done with Tom Jones (1963) a decade before. Whereas that earlier film was part of a movement that challenged societal mores and helped overturn an outdated patrician attitude to sex on the screen, Kubrick’s is a marvel of verisimilitude – an attempt to accurately represent the past on screen. This involved the use of lenses created by NASA to capture interior scenes lit only by candles. At the same time, Kubrick’s script revelled in Thackeray’s humour. For a director known for his seriousness, Kubrick brought a wicked glee to so many of his films. And Barry Lyndon is one of his best.

The Dead (1987)

The legendary Hollywood filmmaker and notorious hellraiser John Huston’s final film, coming after his successful adaptations of Under the Volcano (1984) and Prizzi’s Honor (1985), is an adaptation of James Joyce’s 1914 short story, taken from his collection The Dubliners. It mostly unfolds over the course of an annual dinner party hosted by Gretta and Gabriel Conroy (Anjelica Huston and Donal McCann). Adapted by his son Tony, Huston’s film is a minimalist classic, drawing out the themes of Joyce’s tale as his camera weaves amongst the guests. Fred Murphy’s cinematography keeps the light low, with shadows reigning over the dinner table. And Angelica Huston, who stole Prizzi’s Honor with her Academy Award-winning performance, is sublime here. Her filmmaker father knows it, allowing the action to revolve around her.

My Left Foot (1989)

This impressive account of the life of artist Christy Brown, whose cerebral palsy left him with no alternative but to find a unique way to paint, is anchored by an Oscar-winning performance from Daniel Day-Lewis. Conveying the physical duress Brown experienced in his adult life, yet never foregoing the emotional and creative richness of his inner existence, Day-Lewis’ portrayal is matched by the attention the director Jim Sheridan pays to the world around the painter.

The Field (1990)

Sheridan followed up My Left Foot with this stunning showcase for screen legend Richard Harris, who plays ‘Bull’ McCabe, the bullying patriarch of a rural Irish family, who refuses to let a plot of land be sold to an American investor. Essentially an Irish-infused Western, with Harris’ Bull, Sean Bean’s Tadgh and the McCabe family’s cohorts resembling the Clanton gang of Tombstone, Sheridan’s film is a study in hubris and of a society unwilling to accept progress.

The General (1998)

John Boorman, the filmmaker behind Point Blank (1967), Deliverance (1972) and Excalibur (1981), had long adopted Ireland as his home by the time he made this comedy-drama about the notorious Irish burglar, which won him the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival. Brendan Gleeson shines as Martin Cahill, portraying the criminal as a charming conman, whose disregard for the establishment saw him fall foul of both the law and the IRA. Released in black and white, it’s a striking film. And one close to Boorman’s heart – his home had been one that Cahill’s gang robbed.

The Magdalene Sisters (2002)

It’s hard to believe that the Magdalene convents remained operational until the mid-1990s. It’s where young women were sent if they had become pregnant or didn’t abide by society’s rules. Their treatment in these places, run by nuns, was inhumane. Peter Mullan’s second film, after his impressive Glasgow-set debut Orphans (1998), doesn’t shy away from the sadistic treatment the young women were exposed to, but it never wallows in it, instead focusing on their spirit as they were trapped in this system.

Hunger (2008)

The artist Steve McQueen’s first foray into feature filmmaking not only proved a resounding critical success, it also gave us one of the most emotional and politically charged accounts of the Troubles. Co-written with acclaimed Irish playwright Enda Walsh, Hunger charts the last days in the life of IRA member, political activist, prisoner and hunger striker Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender). Unflinching in its portrayal of Sands’ deterioration – as part of his performance the actor lost a significant amount of weight – the film also details the spiritual battle within the drama, most pointedly in an intense encounter between Sands and a priest, played by Liam Cunningham.

The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006)

The acclaimed social realist filmmaker Ken Loach received his first Palme d’Or for his visually resplendent and politically charged account of the fight for Irish independence in the 1920s. It is very much of a piece with the director’s earlier Land and Freedom (1995), about the Spanish Civil War, in the way the film navigates the various divisions and fissures in the resistance to British rule. In this instance, that rivalry is presented through the strained relationship of two brothers, played by Cillian Murphy and Pádraic Delaney. The film caused some controversy at the time of its release, facing accusations of being anti-British. But it is now regarded as one of the key films dealing with this period of history.

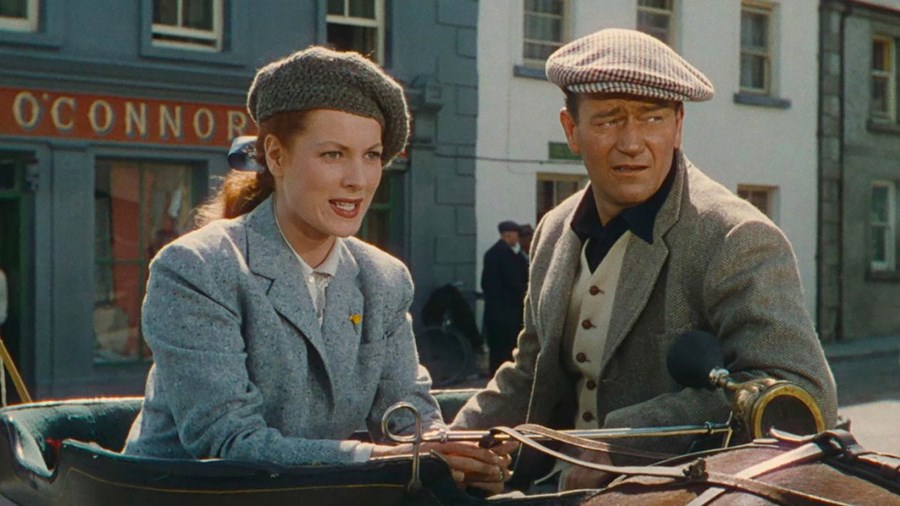

The Butcher Boy (1997)

A veritable institution in Irish cinema, Neil Jordan had amassed an impressive body of work – including The Company of Wolves (1984), Mona Lisa (1986), The Crying Game (1992) and Michael Collins (1994) – by the time he directed his first adaptation of a Patrick McCabe novel. The Butcher Boy follows the childhood of Francie Brady (an impressive Eamonn Owens) as he contends with an alcoholic father and bipolar mother while growing up in 1960s Ireland. Jordan captures McCabe’s irreverent humour perfectly and the film is by turns scabrous and hilarious, while offering a critique of Irish society in that era. Jordan would have similar success a decade later with his adaptation of McCabe’s Breakfast on Pluto (2005).

What Richard Did (2012)

A change of gear from the director of Adam & Paul and Garage, Lenny Abrahamson’s What Richard Did focuses on middle-class life on the suburban outskirts of Dublin. In particular, the titular schoolboy, played by Jack Reynor, who is about to graduate and head off to university. However, a minor incident at a party sets in motion a tragedy and the film’s earlier, lighter mood darkens considerably to grapple with mental health, the notion of personal and civil responsibility and the weight of guilt.

Once (2007)

A young musician teams up with a Polish singer to record a demo tape. He falls for her, but she is already married and longs to be with her family. This simple set-up launches John Carney’s wonderful film, whose success on screen saw it become a runaway stage hit. Glen Hansard had previously been one of the band members in Alan Parker’s The Commitments (1991) and was the bandleader of The Frames. Here, he impresses both as songwriter and star, playing Guy with an everyday charm that grounds the film. Markéta Irglová is equally impressive as the drama’s emotional lynchpin, and John Carney’s relaxed direction makes the most of the Dublin backdrop.

Black 47 (2018)

It’s 1847 and the Great Famine has ravaged Ireland. Feeney (James Frecheville) has returned from service with the British Army to discover his tiny rural family home in tatters. He discovers his mother is dead and brother has been hanged for stabbing a bailiff. When he witnesses first-hand the cruelty of the English masters, he decides to seek revenge, gradually working his way up the chain of command. All the while, he is pursued by a motley bunch of British officers and conscripts, and an old brother-in-arms (an excellent Hugo Weaving). Resembling a rural Point Blank (1967), Lance Daly’s thriller is a taut and unflinching classic.

Intermission (2003)

John Crowley’s raucous portrait of life in present-day Dublin balances knockabout humour with jolts of violence. If Cillian Murphy and Kelly MacDonald’s John and Deidre represent some kind of normality in this world, Colin Farrell is its raging id. The actor had just come off a series of big-budget Hollywood films. Although he shone in Minority Report (2002), Phone Booth (2002), The Recruit, Daredevil and S.W.A.T. (all 2003) did him no favours. His portrayal of Lehiff here was a reminder of just how good Farrell could be – a promise that was fully realised in In Bruges (2008) and his work with Yorgos Lanthimos.

Brooklyn (2015)

A beautiful adaptation of Colm Tóbín’s 2009 novel, Brooklyn stars Saoirse Ronan as Eilis, a young woman in 1950s Ireland who decides to seek out a new life in the titular New York borough, only to find herself torn between the new world and her homeland, and the two men who represent them. Adapted by Nick Hornby, John Crowley’s film perfectly captures the cadences and atmosphere of both worlds. But it’s the emotion Ronan brings to her role that raises the stakes of Eilis’ ultimate decision so high.

Rose Plays Julie (2019)

The less you know about Rose Plays Julie – from Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor, the filmmakers behind Helen (2008) and Mister John (2013) – the better. It’s an exploration of identity and trauma with two women navigating an uneasy relationship determined by past events. The directors’ elliptical style is perfect in drawing us into these characters’ worlds, while keeping us guessing as to their motivations.

Calm With Horses (2019)

A bruising rural crime thriller, Nick Rowland’s Calm With Horses focuses on Cosmo Jarvis’ Arm, a heavy for a local crime family. He is called on when punishment is required, but Arm increasingly finds himself repulsed by this world, desperate instead to spend more time with his ex and their child. But when a con commits an act that requires the ultimate penalty, Arm suddenly finds himself facing the wrath of the gang because of his unwillingness to follow through on their orders. A refreshing take on a well-worn genre, Rowland’s film makes the most of the contrast between the pastoral beauty of the surroundings and the gang’s vicious tactics.

Belfast (2021)

Unashamedly sentimental, revelling in its own artifice, yet remaining true to his memories of growing up a young boy on the streets of the Northern Irish capital, Kenneth Branagh’s paean to Belfast is his finest film since Much Ado About Nothing (1993). It profits in no small part from Jude Hill’s charismatic central performance as Buddy. But the rest of the cast, including Caitríona Balfe and Jamie Dornan as Buddy’s parents, along with Judi Dench and Ciarán Hinds as his grandparents, are all impressive. Ultimately, it’s the energy Branagh invests in Belfast that makes it so compelling.

The Quiet Girl (2022)

Cáit lives on a run-down farm with her parents and an ever-growing number of siblings. She is different from her louder brothers and sisters – more withdrawn, preferring to observe the world than be a part of it. Her parents don’t understand her either and appear happy to send her off to relatives for the summer. It’s in this new home that Cáit flourishes, even if there is a veil of sadness over it. Colm Bairéad’s beautiful, understated The Quiet Girl, set in 1980s Ireland, is a lyrical evocation of an era of a young girl’s gradual emergence into the world, and the first Irish-language film to be nominated for the Best International Feature Oscar. Beautifully shot, the drama is anchored by an extraordinary performance from Catherine Clinch.

kneecap (2024)

A music biopic with a twist: this isn’t a retrospective film, wistfully reminiscing about a long finished artistic career well navigated. Quite the contrary, Rich Peppiatt’s rambunctious dramedy, which took home the Next audience award at Sundance, shows the formation of the anarchic Belfast rap trio Kneecap (played by the band themselves: Móglaí Bap, Mo Chara and DJ Próvai). With considerable style and plenty of swaggering attitude, the film details how the musicians’ crowd-riling Irish songs helped ignite a movement to protect their mother tongue, blasting the dust off the dying language and pulling it into the 21st century.

WATCH KNEECAP IN CINEMAS