It’s been a grand year for biopics. Christopher Nolan broke box office records with Oppenheimer, surpassing Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) as the most commercially successful biopic ever made. It’s also a testament to audiences’ willingness to sit through – for some, more than once – a three-hour film that’s not a sequel, based on a franchise or any other intellectual property, and mostly comprising people talking.

As we go into the awards season, we’ll see Annette Bening in Nyad, an inspiring portrait of an athlete who set out to swim the shark-infested, 110-mile stretch of ocean between Cuba and Florida. In Rustin, Colman Domingo plays Bayard Rustin, who organised the era-defining 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington. In Wildcat, Ethan Hawke directs his daughter Maya as US writer Flannery O’Connor as she attempts to get her first novel published. Sofia Coppola gives us an alternative perspective on one of the great celebrity romances with Priscilla, an account of the relationship between Priscilla Beaulieu and Elvis Presley. And with Napoleon, director Ridley Scott reunites with Joaquin Phoenix for the first time since Gladiator (2000) for this dive into the life of the French emperor. In terms of awards chatter, these heavyweight biopics still lag behind the frontrunner, which kicks off this list of the most singular biopics ever made. Here are the best films based on a true story.

Maestro (2023)

Bradley Cooper’s follow-up to his breakout feature directorial debut is a portrait of the relationship between renowned composer-conductor Leonard Bernstein and his wife Felicia Montealegre. Cooper takes the lead, with Carey Mulligan excellent as the celebrated, Costa Rica-born actor whose life with Bernstein was loving yet complex, as a result of his sexuality and unbridled ambition. Cooper and co-writer Josh Singer steer clear of the momentous artistic triumphs in Bernstein’s life, focusing instead on a more psychological portrait of this icon of American arts and culture. Even in a field of biopics as competitive as this awards’ season has offered up, Maestro has already cemented its position as the one to beat.

Napoleon (1927)

Ridley Scott not only has the challenge of current biopics to face off against, his film will also be judged against one of the towering achievements of pre-sound cinema. Abel Gance’s portrait of the French leader is an impressive analysis of one man’s desire for power and an epic restaging of the tumultuous events that such ambition incited. His battle scenes were staged on such a grand scale that Gance shot them with three cameras, with the footage projected across three massive screens.

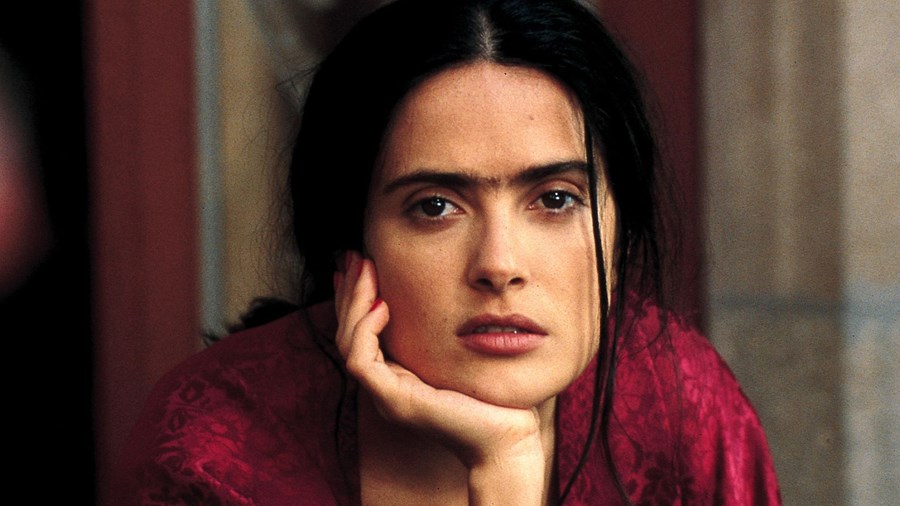

Frida (2002)

There was a long time when Frida Kahlo’s life and work was overshadowed by her husband and fellow artist Diego Rivera. These days, not so many people know of Rivera, while Kahlo rightly ranks as one of the most formidable and admired artists of the 20th century. Julie Taymor’s film might not have been the lightning rod that shifted this perception, but it certainly helped. Originally a vehicle for Madonna, Kahlo here is played by Salma Hayek, who gives a career-best performance, revelling in her subject’s complexity. Taymor employs every cinematic trick to capture Kahlo’s vision of the world, resulting in one of the most glorious, inventive and dazzling biopics ever made.

Shirley (2020)

Shirley Jackson wrote unnerving, haunting stories. In indie darling Josephine Decker’s biopic-of-sorts (it’s based not on a biography, but Susan Scarf Merrell’s 2014 novel) the author’s life is as – if not more – beguiling and troubled than her fiction. Decker’s direction skilfully conjures up the crepuscular environment Jackson and her husband (brilliantly portrayed by Michael Stuhlbarg) live in, while Sarah Gubbins’ screenplay captures the stuffiness of a closeted intellectual world. But it’s Elizabeth Moss, in the title role, that proves to be the film’s trump card. An actor skilled at immersing herself completely in a role, her Jackson is a formidable creation.

Citizen Kane (1941)

Who says that biopics have to be factual? Orson Welles, aged just 26, produced, co-wrote, directed and starred in this fictional portrait of a media magnate, loosely based on the life of real-life newspaper mogul and political troublemaker William Randolph Hearst. Opening with Kane’s death, a newsreel detailing his public life, and meeting of journalists and editors keen to get a ‘scoop’ on who the real Charles Foster Kane was, the film progresses into a multi-perspective portrait of the Welles’ troubling character, in an attempt to understand what drove him.

Persepolis (2007)

There’s no reason why animation can’t embrace the biopic and, with co-director Vincent Paronnaud, Marjane Satrapi brings her acclaimed four-volume graphic novel/memoir to the screen. Satrapi was eight years old when the Iranian Revolution took place and her film details life in this new, more restrictive environment and spans just over a decade. What’s most striking about the film is the confidence with which the story is told – Satrapi cleverly recognises that the personal becomes universal if a story is told with clarity and honesty. Alongside Ari Folman’s equally bold Waltz with Bashir (2008), Persepolis marked a sea change in what animated features could achieve – and the size of the audience eager to watch them.

La Reine Margot (1994)

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, which began on the night of 23-24 August 1572, remains one of the bloodiest moments in European history. Leading Huguenot (French Calvinist Protestants) dignitaries had arrived in Paris for the wedding of French Catholic King Charles IX’s sister Margaret to their King Henry III of Navarre. Believed to be instigated by Charles’ mother Queen Catherine de Medici, a Catholic mob murdered Protestants at random, changing the course of the French Wars of Religion in their favour. Patrice Chéreau’s stunning account of what took place combines the biopic and historical epic in a style that more closely resembles The Godfather than any previous pre-20th-century-set period drama. It’s a bloody, intoxicating snapshot of the past.

Amadeus (1987)

A number of major biopics swept the Oscars in the 1980s. Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982) was reverential but, save for a few scenes, cinematically inert. Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor (1987) was an opulent, visually dazzling portrait of China’s last emperor Pu Yi. Miloš Forman’s Amadeus (1984), adapted by Peter Shaffer – with Zdenek Mahler – from his stage play, stood above them. What makes the film unique is its irreverence. Mozart is acknowledged as a genius, but he’s also an ass, and whose combination of brilliance and immaturity infuriated Antonio Salieri, a composer who, in any other era, would have been fêted, but could never escape the shadow of his nemesis. It’s impossible not to believe that Christopher Nolan didn’t use this as the template for the battle of wits between Oppenheimer and Lewis Strauss.

Lawrence of Arabia (1961)

This is the gold standard of the epic, life-writ-large biopic. What makes David Lean’s account of divisive figure T.E. Lawrence so great is the intimacy of the portrait. The epic desert sequences are shot on a suitably grand scale, mirroring the ambitions of a Western interloper in Arabic culture, but the focus on Lawrence’s personality – and, by extension, his flaws – emboldens the contrast between the public persona and private person, all of which is brilliantly conveyed by Peter O’Toole in his first major screen role.

Malcolm X (1992)

An air of indifference pervaded many reviews of Spike Lee’s magisterial biopic upon its initial release. After his electric contemporary dramas Do the Right Thing (1989) and Jungle Fever (1991), he had opted for something more conventional – a blow-by-blow account of the life of the controversial Black activist. They couldn’t be more wrong. This is Lee at his incendiary best. That is immediately demonstrated in the title sequence, which intercuts Zapruder-like footage of the L.A.P.D. beating of Rodney King with a burning US flag, played out to Malcolm X’s iconic Plymouth Rock speech. Denzel Washington has rarely been better in the lead role, Terence Blanchard’s score is a jazz-tinged masterpiece and Lee’s roving, probing direction results in an incisive and ultimately moving portrait of an extraordinary figure.

Raging Bull (1980)

It could have been any number of Martin Scorsese movies. Goodfellas (1990). Or The Wolf of Wall Street (2013). Or The Irishman (2019). Perhaps, even, The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). But the combination of Paul Schrader and Mardik Martin’s searing screenplay, Robert De Niro’s staggering performance and physical transformation, and Scorsese’s direction make Raging Bull one of the most essential biopics. It’s a piercing portrait of masculinity in all its toxicity, and a striking examination of the tenets of faith in all its forms.

I, Tonya (2017)

To sporting films what The Wolf of Wall Street is to the cinematic financial world, Craig Gillespie’s scabrously funny, expletive-laden account of the rise, fall and criminal actions of Tonya Harding is dominated by the performances of Margot Robbie in the lead role and an Oscar-winning Allison Janney as her chain-smoking, potty-mouthed mother. Wildly irreverent, the film’s tone perfectly captures the batshit-crazy scheme Harding became involved in to secure a place on the US Olympic team, while also offering up an incisive portrait of the world she came out of.

Jackie (2016)

She was the queen of Camelot. Jackie Kennedy, as she was known when this film is set, was the symbol of a nation in mourning – the wife of a murdered US president. Pablo Larraín’s film, working with a stunning script by Noah Oppenheim, defies every rule in the conventional biopic playbook. It’s history minus the grand narrative, a multi-perspective portrait of a very public figure in the aftermath of a tragedy, whose whole life, one lived mostly through her husband, is reduced to rubble. Structured around an interview given with a journalist, the film presents Jackie (played in a pitch-perfect performance by Natalie Portman) as a more independently minded and resilient woman than a nation gave her credit for.

Julie & Julia (2009)

Nora Ephron’s adaptation of blogger Julie Powell’s account of her attempt to cook all the recipes from TV cooking icon Julia Child’s first book perfectly balances that story with an insight into Child’s own life. Amy Adams is great as Powell. But the stars are Meryl Streep and Stanley Tucci as Child and her husband Paul, and Ephron’s joyous screenplay, which is as complex, yet deceptively light, as one of Child’s soufflés.

12 Years a Slave (2013)

Steve McQueen transforms the tastefulness of the prestige, Oscar-bait biopic into a searing, visceral experience. Adapting Solomon Northup’s memoir of how a Free Black man was kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841, the filmmaker refuses to shy away from the savagery of white plantation owners and their white employees’ treatment of Black slaves. It’s a moving and frequently disturbing film, with stunning performances by Chiwetel Ejiofor and Oscar-winner Lupita Nyong'o. It deservedly walked away with the Best Picture award.

Lincoln (2012)

The obvious choice would be Schindler’s List (1993). But Steven Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner’s decision to focus their drama on a single period in the US President’s life – his successful attempt to abolish slavery via the passage of a Constitutional amendment – makes for a riveting, action-free yet thrilling drama. The opening Gettysburg Address scene starts things a little cornily, and there is the odd stilted moment. But thanks to Spielberg’s pacing and Daniel Day-Lewis’ incredible performance – ably supported by a typically strong Tommy Lee Jones, Sally Field and scene stealing Lee Pace – Lincoln is a rewarding retelling of a key moment in US history.

24 Hour Party People (2002)

Forget the recent Queen and Elton biopics. And Elvis (1979 & 2022), Ray (2004), Funny Girl (1968), Walk the Line (2005) and Straight Outta Compton (2015). Michael Winterbottom’s account of the Madchester scene in the 1980s and early 1990s is the most quintessential, inventive, wild music biopic. (Only Todd Haynes’ hard-to-see Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1988) comes close.) In form and style, it perfectly captured the era that saw the rise of Joy Division, New Order and the Happy Mondays. But presented from the perspective of self-effacing TV presenter-cum-music mogul Tony Wilson it is also one of the funniest films about the music industry.