Editor Úna Ní Dhonghaíle talks about her collaboration with Kenneth Branagh on Belfast, his spirited, semi-autobiographical evocation of his youth.

Ken wrote the most beautiful script, which resonated with all who had the pleasure of working on the film. As a director, he chose his coverage wisely. Several of the domestic scenes were covered in as few as three shots, but the riots were shot with two cameras and produced a lot of coverage. We worked really well together in the restructuring of certain scenes, which allowed for a particular movement throughout the film. We told the story through the eyes of Buddy [Jude Hill], but we could equally expand that point of view and shift briefly to Ma’s [Caitriona Balfe] perspective. Sometimes it was in the way Ken framed certain scenes, such as the one where Ma gets the letter from the taxman and goes into the sitting room to read it. Ken and Harris [Zambarloukos, cinematographer] kept the camera on her through the doorframe. We did have coverage within the room, but we held on to that shot because it was so beautiful. You could see Buddy and his brother Will [Lewis McAskie] on the left side of the frame and Ma on the right. The boys are having breakfast and chatting, oblivious to how tense Ma is in the next room. Compositions like that were just wonderful. I could stay on that for a while, before going into the room with her.

The first cut of the film was a lot longer. We shortened it [to 98 minutes] by collapsing scenes and creating vignettes. A great example of this is the sequence where Van Morrison is singing Days Like These. It was a critical sequence in terms of allowing the audience to empathise with Ma’s predicament. We had to convey why Ma was reticent to leave and what was so wonderful about Belfast, even as things were getting worse. It was their home and, as Van Morrison sings, on days like these – with families together and children playing, even with the barricades up – it was the best place to be.

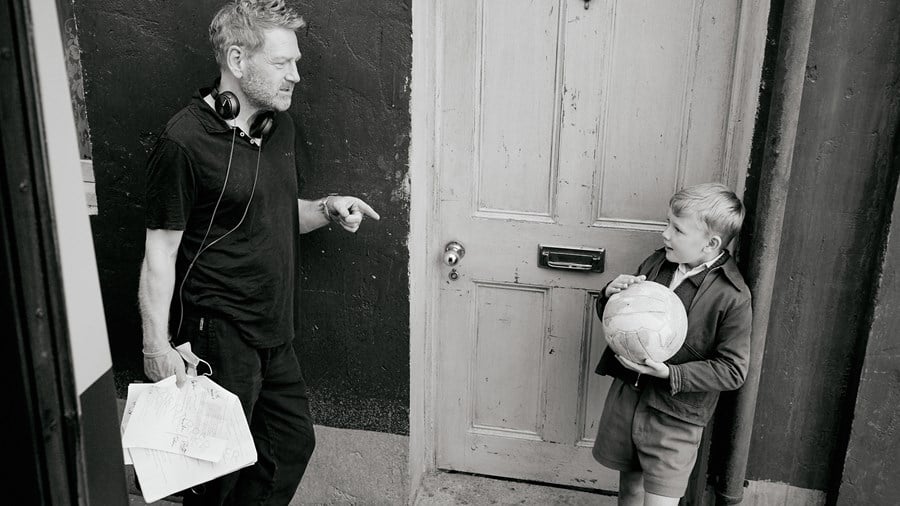

Kenneth Branagh on the set of Belfast with Jude Hill

Ken and I edited this film remotely, but we spoke every day and worked as if we were in the same room. We would forensically explore the rushes, picking out scenes and figuring out how best to include them. After the lockdown in 2020, my family moved back to Dublin from London and, as someone who is always working in and commuting to London, I identified strongly with Pa. One day, as I was pulling the film together for Ken, it occurred to me that the early-morning scene of Pa [Jamie Dornan] leaving for England and Buddy waving sleepily from the window might be more powerful if it came later in the film, after the Christmas scene when Buddy shouts ‘I don’t want to leave Belfast!’. I suggested the idea to Ken and he said let’s try it. Once we moved the scene, it worked, both on an emotional and psychological level. It also opened up the earlier part of the film and Ken suggested using Van Morrison’s song Carrickfergus for that scene and it felt right.

Sound is also an important character in the film. I studied at the NFTS where I was introduced to brilliant British films, like Terence Davies’ Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988). His use of sound to evoke memory was inspiring. Before principal photography began, I asked Ken which sounds he remembered hearing as a child in Belfast. He mentioned the rag‘n’bone man, ice-cream vans, trains constantly passing, ship horns and the docks. Our sound supervisor Simon Chase was wonderful in this regard and sent sound effects to me. With my assistant editors, we began to create a rich sound bed of ship horns and trains before shooting even began. My dad even recorded the local rag‘n’bone man with my phone, which we were able to preserve within the mix. It helped create the authentic Northern Irish ‘voice’, which, along with the vernacular, added to the musicality of this world.

Cinema is important to the film and Ken’s script always specified that movies shown in it would be in colour. We felt that the first cut to colour should herald a more dramatic entrance. Rather than use the beautiful cinema exteriors that Ken shot, I moved a scene with a neighbour encouraging Pa not to be a ‘lone ranger’ as they put the bins out and hold a fraction longer than necessary on the bin before cutting to the fiery orange explosion that starts One Million Years B.C. (1966). This felt more visceral.

Ken is also interested in stolen moments. If something goes wrong, or the actors make a mistake and laugh, he will be interested in the truthfulness of that laugh. So, in the cinema, when Granny [Judi Dench] says to Buddy, ‘Stop you talking’ and he laughs, that was a real laugh from Jude. They generally kept the cameras running between the takes so managed to capture it. Judi Dench is such a great character, she had little Jude in fits of giggles the whole time. And I knew, having worked before with Ken on All Is True (2018) and Death On The Nile (2022), that we could use things like that.

Belfast (2021)

Ken is also influenced by the Western, particularly in the stillness of his shooting style, the strength of performances and in the direct references to films like High Noon (1952). We use a kind of magical realism during the final stand-off between Pa and Billy Clanton [Colin Morag], which is shot as if it’s a Western, with some iconic high angles and, when the two men face each other, the theme to High Noon is playing. On an implicit level, this allows the audience to see the conflict through Buddy’s eyes.

Belfast is a love letter to the great city of Ken’s birth, to his beautiful family and neighbours of all persuasions, and to the little boy who witnessed so much change. It was a privilege for me to join Ken on this journey.

This article originally appeared in the Awards Journal, our awards-season magazine. Pick up your free copy at your local Curzon while stocks last.