As Fast Times at Ridgemont High celebrates its 40th anniversary, Georgina Guthrie explores the ways its director’s comedies joke about sex, pregnancy and plastic surgery as a means of challenging the status quo.

As a filmmaker, Amy Heckerling focuses on women navigating transitional phases – whether that’s grappling with the trials of pregnancy, ageing bodies or adolescence. Tonally, her films ebb and flow with the ups and downs of life, though they never plummet to despair: optimism is the thread that runs through her work. Her breezy, fun-loving movies are buoyed up by unabashed nostalgia, playful pop soundtracks and gross-out gags that invite audiences to share a laugh at the occasional indignity of having a body – specifically a changing female one – while also interrogating the larger implications of these throwaway jokes.

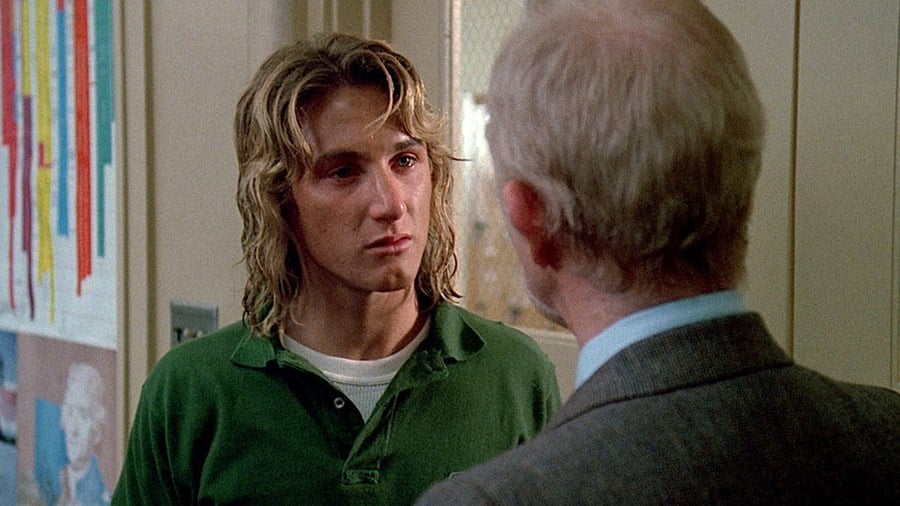

Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982)

At first glance, her best known films – the remarkably assured 1982 debut Fast Times at Ridgemont High (which celebrates its 40th anniversary this week) and 1995’s Clueless – slot neatly into a rich canon of movies about teens growing up and careening through their youth in a very physical, libido-driven way, as well as negotiating the stormy seas of lust and love. Youngsters fellate carrots in Fast Times, whereas Clueless sees the iconic, yellow-tartan-wearing Cher Horowitz (Alicia Silverstone) set food alight and crash her car. But what sets these films apart from the ‘teen boys lose their virginity’ romps that preceded them is their decidedly female perspective, which, after decades of male-dominated stories, were as bracing as slipping into a cool pool on a hot summer’s day for contemporary audiences.

Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982)

In Fast Times, we follow Stacy (Jennifer Jason Leigh), a 15-year-old feeling her way into adulthood, which, in the grand tradition of teen comedies, involves plenty of sex – yet Heckerling refuses to make Stacy the butt of some raunchy joke, or an object with no desire or autonomy. Instead, she’s an instigator, sneaking out to hook up and experiencing all the same cringing awkwardness we’d expect from Pee Wee in Porky’s (1981) or Gary in The Last American Virgin (1982). Heckerling challenges existing notions about female sexuality through her carnally adventurous protagonist. Sex isn’t something Stacy submissively relinquishes, she actively seeks it out. Far from the neatly choreographed images of female desire we’re used to seeing in film and porn, Stacy’s encounters are clumsy and funny (even if they’re ultimately unfulfilling).

In a move that surely felt radical in the Eighties, both sex scenes in Fast Times are shot from the female perspective. When Stacy sleeps with her 26-year-old lover (who doubts she’s 19 as she claimed), Heckerling’s camera focuses first on her naked, vulnerable body crushed between his and a concrete bench, then pans to a dim light bulb and ridiculous graffiti above them. It’s cringingly uncomfortable. Stacy’s second attempt is equally as awkward and, worse yet, ends in an unplanned pregnancy, which Stacy chooses to abort. Again, the filmmaker approaches traditional teen-movie fare with a refreshing spin, forgoing the expected pregnancy test-and-tears scene. Stacy simply tells the father her plan, asks him to foot half the bill, and give her a ride to and from the clinic (he fails to hold up his side of the bargain and is rightfully ridiculed by his classmates). After her abortion, Stacy picks up where she left off – sunbathing, selling pizza and looking for love in her youthful, trial-and-error way. Heckerling destigmatises abortion with her considered, unsensationalist approach to it.

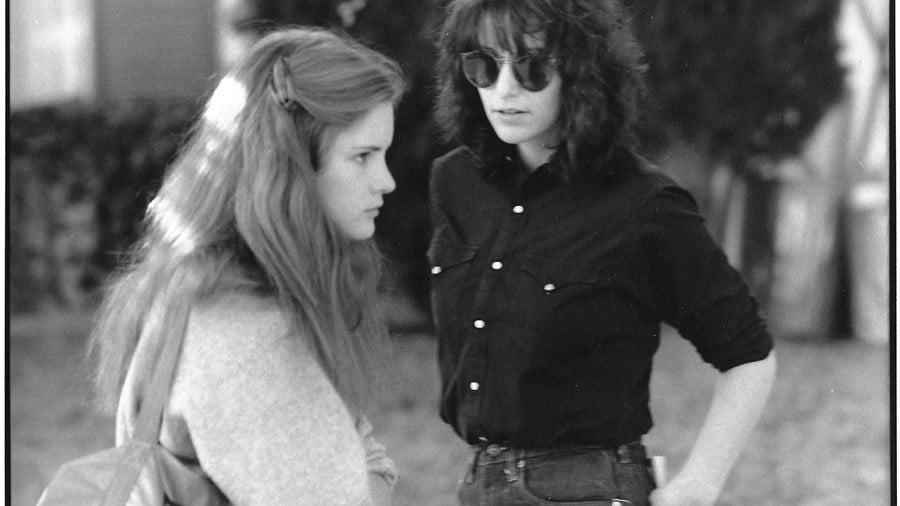

Jennifer Jason Leigh and Amy Heckerling on the set of Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982)

Questions of the body crop up throughout the director’s filmography. Like Fast Times, her three most accomplished rom-coms Look Who’s Talking (1989), I Could Never Be Your Woman (2007) and Vamps (2012) realise that there is humour to be found in having a female form. In Look Who’s Talking, for example, the bodily functions of 32-year-old accountant Mollie (Kirstie Alley) – who’s laden with an unplanned pregnancy and working out whether her friendship with the charming yet unruly James (John Travolta) is something more – form the film’s comedic backbone. Her morning sickness-induced vomiting interrupts a conversation with her co-workers, and breastfeeding provides gentle chuckles when Mollie waits until after James has sipped from a bottle of breastmilk before telling him what it is. By lightly poking fun at the physical side-effects of pregnancy, Heckerling normalises a natural part of womanhood that has long been misunderstood or, at worst, cloaked in shame.

The comedy draws out this more serious undercurrent in its exploration of why Mollie chooses to see her baby to term. She doesn’t particularly want to be a mother, but a male doctor insensitively reminds her that ‘her biological clock is ticking’, which encourages her to have the child. Later, when Mollie explains she’s keeping the baby to the philandering ex-lover who fathered it, she is careful to reassure him she won’t ask for anything, entirely taking on the physical and emotional burden of parenthood. These fraught, yet always funny, conversations are centred around a body that is given an expiry date. Despite this cold medical analysis, we are shown that Mollie is still in the prime of life: she desires and is desired, and her body is so much more than its ability to gestate a child.

In I Could Never Be Your Woman, Heckerling explores a wider range of gendered physical pressures through Rosie (Michelle Pfeiffer), who fulfils a number of roles as a single mother trying to raise her teenage daughter Izzie (Saoirse Ronan), a female producer working in a male-dominated production studio and a 45-year-old woman dating a man 11 years her junior (Paul Rudd). The physical comedy here is more shocking, since Heckerling employs grotesque imagery for laughs. The opening credits feature graphic scenes of botched plastic-surgery procedures, setting the stage for a film that grapples with the paradoxical pressures placed on women to look youthful yet also act ‘their age’. This theme is deepened through the mother/daughter and older woman/younger man relationships that drive the narrative. In one comical sequence, Rosie storms into Izzie’s school to confront her male teacher about his poor handling of her menstruation. For all its amusing repartee, their shouting match serves to critique the inflexibilities that make schools hostile places for young girls.

I Could Never Be Your Woman (2007)

Rosie has a close bond with her daughter. Heckerling emphasises the harmony in their relationship with her varied soundtrack, where then contemporary teen favourites Britney and Blink 182 singles mingle with The Cure, Michael Jackson and Status Quo tracks that would have been hits in the late Seventies when Rosie was her daughter’s age. I Could Never Be Your Woman’s intergenerational female camaraderie extends to Vamps, a film about two female vampires who help each other abstain from drinking human blood. Vampirism proves surprisingly fertile ground for Heckerling’s body-centric humour as food (in this case, blood) cravings and fake-tan mishaps bring oddly relatable gross-out comedy. Again, unruly bodies are a source of laughter, but it is the strong connection between these women that gives the film its lasting emotional impact. In the end, Alicia Silverstone’s more mature vampire gives up eternal youth and dies so her best friend (Krysten Ritter) can enjoy mortal motherhood.

There’s a gentle push and pull between the comedic and the serious throughout Heckerling’s work. Though slapstick humour and bawdy jokes abound, the director always grounds them in truth, pragmatically dealing with taboo topics in her mainstream comedies. Life transitions can be isolating and disorienting, but Heckerling’s characters never go it alone: female friendships form the bedrock of her oeuvre. In bringing these experiences to the screen in a playful, relatable way, Amy Heckerling introduced mass audiences to all the messy, chaotic poetry of being a woman.

EXPLORE OUR COMING-OF-AGE COLLECTION ON CURZON HOME CINEMA